Health Care Access & Coverage

News

King vs. Burwell Through The Lens of Economics

Will the Supreme Court Drop an 'Adverse Selection' Bomb on 34 State Marketplaces?

If the Supreme Court rules for the plantiff in King vs. Burwell, nearly 8 million low-income people in 34 states will be denied Affordable Care Act insurance subsidies.

Now that Supreme Court arguments over the Affordable Care Act (ACA) are over, and the health insurance status of millions of Americans awaits a June decision, lets take a look at some of the economics of what a ruling for the plaintiff could mean.

The lawsuit seeks to deny subsidies to individuals who purchased insurance policies in the 34 states that use the federal insurance marketplace or “exchange.” While the legal question before the court is not an economic one, to understand the effect of a plaintiff victory, one must first understand the structure and economics of the health insurance marketplaces. The Justices implicitly acknowledged this, referring repeatedly to a “death spiral.”

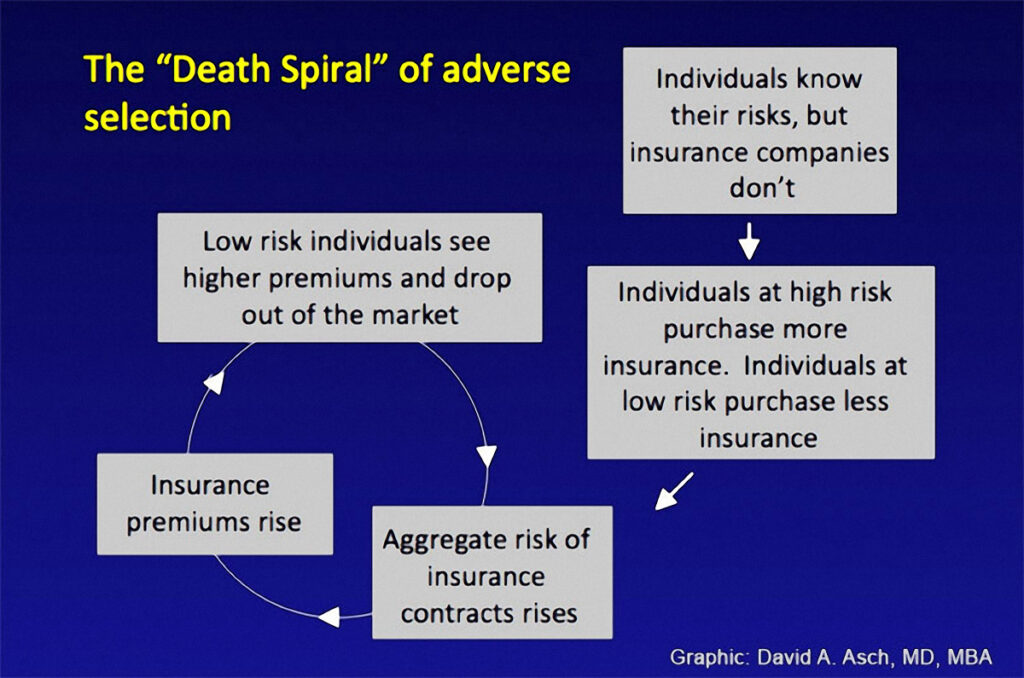

A key to understanding death spirals and similar pathologies of health insurance markets is the concept of “adverse selection,” a cycle of events that cause premiums to become more expensive.

Prior to the ACA, individuals who wished to buy insurance themselves — typically because they were unable to obtain it from their employer or a government program — would approach insurance companies, directly or through an insurance broker. People with a past medical history that suggested they might have high medical bills in the future could be refused coverage or charged a prohibitive premium.

The ACA created new health insurance marketplaces, or “exchanges,” where these individuals can go to one website and see many plans offered for sale, streamlining the process and making it easier for individuals to shop for the best plan for them. States chose whether to create their own marketplaces (state-based marketplaces or SBMs) or allow the Federal Government to create one for them (federally-facilitated marketplaces or FFMs). Currently, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, there are 7.5 million people receiving subsidies in the 34 states that opted for a federal exchange.

of Pennsylvania health economics

MD/PhD student interested in

health insurance, access to care,

women’s health, and the impact

of financial incentives on health

care utilization.

Key regulations

The ACA also put into place several key regulations. First, it created a mandate that anyone who could afford to buy insurance but chose not to would have to pay a penalty. Next, it included subsidies to ensure that insurance would actually be affordable. Individuals for whom health insurance costs would exceed 8% of their household income after taking the available subsidies into account are exempt from paying the penalty if they do not purchase insurance. The subsidies apply to people with incomes below 400% of the federal poverty limit (FPL), with greater subsidies as incomes decline.

Third, no one could be refused coverage for a pre-existing condition, a rule known as “guaranteed issue.” Last, pricing of premiums was only allowed to vary for a population in an area (with limited exceptions for age, smoking status, etc.), rather than the health status of the individual buying insurance, protecting sick and unhealthy people from being charged extremely high premiums. This restriction is called “community rating.”

Subsidies in 34 states

The prior Supreme Court case , in 2012, challenged the individual mandate. King vs. Burwell, the current case, calls the legality of these subsidies into question in 34 states. The lawsuit charges that while the ACA explicitly says subsidies should be made available in states that run their own exchange, the law was intended to deny subsidies to enrollees in states which allowed the Federal government to set up the exchange.

What will happen if the Supreme Court rules that these subsidies cannot be made available? Two of these regulations, subsidies and mandates, serve to decrease the cost of insurance to consumers. That price reduction balances out the other two regulations, guaranteed issue and community rating, which tend to increase premium prices. To understand why each of these works in the way that they do and what might happen if you remove one of these regulations, we have to understand the economic theory of adverse selection.

of Pennsylvania health economics

MD/PhD student interested in the

industrial organization of the

unscheduled care system, access

to care and insurance, and

financially integrating population

health into the medical system.

Adverse selection

Adverse selection is when sicker people are more likely to buy insurance than healthy people, and insurance companies are not able to adjust their premiums to account for the higher risk. This can happen when people who buy insurance have more information about their likely health costs than insurance companies. This drives the average healthcare costs of the insurance plan higher, since the typical enrollee is sicker.

Adverse selection is why an individual mandate and subsidies lower premium costs. These two policies bring lower cost (i.e. healthier) individuals into the marketplace. These are people who, on average, expect to have health costs notably lower than the cost of the insurance premium, and for whom not buying health insurance is a rational financial choice. The mandate brings these people into the market by raising the cost of not buying insurance; subsidies bring them in by lowering the cost of buying insurance. When these healthier people enter the marketplaces, premium prices go down.

The other two regulations — guaranteed issue and community rating — raise premium prices for most because they don’t allow insurers to price premiums at the individual level. For instance, for a patient with a new diagnosis of cancer, expected health costs for a year of insurance could easily run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars. Rather than allowing an insurance company to charge this individual hundreds of thousands of dollars for a year of insurance, or refuse to insure them entirely, these policies spread the cost of paying for this person’s health care across many people’s premiums.

The ‘death spiral’

Without a mandate and subsidies, guaranteed issue and community rating alone quickly raise premiums, resulting in a feedback loop called a “death spiral.”

In a death spiral, prices rise so much that over time the person who last year decided that it was barely worth purchasing an insurance contract decides this year to forgo insurance and risk the financial burden of getting sick instead. If this happens year after year, only the very sickest are left insured — and at very high prices.

Complex set of effects

A ruling striking down subsidies would have a complex set of effects on the various people right at the edge of purchasing an insurance contract. Insurance markets do not cross state lines. Thus the people who would lose their subsidies would be the ones living in the 34 states that chose to allow the Federal Government to create their marketplaces.

If the subsidies are eliminated in states using the federal exchange, this could have one of two effects on an individual who was previously eligible for a subsidy (under 400% FPL), depending on their income and the unsubsidized cost of insurance plans available in their state’s marketplace. If the cost of unsubsidized health insurance is more than 8% of their income, they will be exempt from the individual mandate if they choose not to buy insurance. If the cost is less than 8% of their income, they will still be subject to the mandate and can choose to either buy an unsubsidized plan or simply pay the penalty for going uninsured.

To make things less confusing, lets talk about four individuals. Subsidized Sally expects to have enough health costs that it is just worth it for her to buy insurance if subsidies remain. Intermediate Ian and Mandate Megan both are eligible for subsidies, but have higher expected medical costs than Sally. They both think it would be barely worth purchasing insurance without a subsidy, but only because their expected health costs plus the price of the tax penalty for not purchasing insurance would be greater than the cost of a health insurance premium. Intermediate Ian has an income high enough that his premium without a subsidy would still leave him subject to the mandate. Mandate Megan, on the other hand, has a lower income such that her unsubsidized premium would be more than 8% of her income. High Harry has expected health costs above Megan and Ian’s, such that he finds it worth purchasing insurance without either a subsidy or mandate at current prices. To simplify further, none of these three will be what economists refer to as “risk averse” individuals, in that they don’t much value the financial protection that comes from insurance and are just looking for the best deal on average.

Adverse selection at work

If King eliminates subsidies, in the first year Sally will decline to purchase insurance. Megan will not buy insurance either, because without the subsidy she is not subject to the mandate (her unsubsidized premium is more than 8% of her income). Ian and Harry will both buy. Because Megan and Sally had expected health costs lower than that year’s premium, their leaving the market will cause next year’s premium to increase — that’s adverse selection at work.

In the second year, Ian will now drop out because of the adverse selection-driven increase in the price of his insurance premium. This drives up the third year’s premium. High Harry would have purchased insurance at the initial prices even without a subsidy or a mandate, but at some point as the death spiral progresses, prices are too high for it to be worth it for him, and he too drops out.

Thus, one implication of adverse selection is that even if nearly everyone wants insurance and is willing to pay more than their expected cost of medical care to obtain it, the market will not necessarily ensure that everyone is able to purchase insurance. Consequently, government intervention in the form of a subsidy and/or a mandate could improve the well-being of society as a whole. Were that the entire story then very little data would be required to determine how important the mandate is to the overall health reform package. However, adverse selection does not always exist in insurance markets. Even when it does exist, it can be small enough that markets do not fall apart. Therefore, we have to examine the data to see what would happen if the Supreme Court eliminates subsidies for individuals in states with federal exchanges.

What does the most recent research tell us?

The possible effect of a lawsuit is difficult to predict because there are no past public policy changes like this that we can study. Instead, the research in this area uses microsimulation models of synthetic populations of individuals for whom extensive information has been gathered about their health, families, and economic circumstances. These models make assumptions about how individuals will choose insurance based on the options that are available to them, and then simulate the effects of policies by changing the available health insurance options in the simulation.

A few studies have specifically examined the potential impact of a ruling in favor of the plaintiffs. Specifically, they try to estimate how many people would drop coverage in the individual market, and how much this would worsen adverse selection in the form of raising premium costs in these marketplaces. One study, from the RAND Corporation estimated that eliminating subsidies in federal exchange states would result in enrollment in marketplace plans in those states falling by 70% (9.6 million fewer enrollees), and insurance premiums increasing between $1,610 to $5,060 per year. A second study by the Urban Institute estimated effects of similar magnitude on premiums and insurance coverage.

Another study, also by RAND, examined the characteristics of the people who would lose subsidies if the Supreme Court decides in favor of the plaintiffs, and found that 99% of them would face insurance prices so high that they would be exempt from the individual mandate. Thus, the evidence suggests that there are a lot more Mandate Megans than Intermediate Ians in these markets.

The bottom line

The available evidence suggests that a ruling for the plaintiffs could destabilize the individual markets in the 34 states with federally-run marketplaces. How these states might respond is unknown. In the event subsidies are eliminated, some states may find workarounds. Perhaps they could legally establish an exchange but leave the logistical responsibilities to the Federal Government, essentially establishing a state-based marketplace “in name only.” However, that would rely on states actively seeking a workaround and such a strategy being legally viable.

Nearly 8 million subsidized individuals are currently at risk of losing subsidies. But these numbers understate the potential impact of a ruling in favor of the plaintiffs.

Eliminating the subsidies would not just narrowly affect those who were subsidy-eligible, but also those who were not, because of the spillover effects of adverse selection. In the absence of the subsidies, but the continued presence of community rating and guaranteed issue, adverse selection will likely make insurance premiums more expensive for everyone in these markets. The result could be substantial dysfunction in the health insurance marketplaces in over half of the states in the U.S.