How Hospitals Can Ease Staff Burnout—and Improve Patient Safety

A Major European–U.S. Hospital Study Finds That Changing How Hospitals Are Organized Reduces Burnout and Turnover While Improving Care Quality

Health Care Payment and Financing

Despite grinding through billions of dollars in grants and massive amounts of work managed over 16 years across 50 states, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation’s effort to convert U.S. health care from fee-for-service to a value-based care payment model has largely stalled. Few are more frustrated about that than Liz Fowler, PhD, JD, who headed the agency from 2021 to 2025 and was a featured speaker at the Feb. 3 Policy Seminar at the University of Pennsylvania’s Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics (LDI), where she discussed CMMI’s challenges.

Speaking to an auditorium of health services researchers at the event, titled “Health Policy at a Crossroads: Protecting Progress and Building for the Future,” Fowler detailed how progress toward a value-based care transition was stymied in part by CMMI’s pilot evaluation framework, which often made success structurally impossible, even when care delivery in some pilot programs was improving.

Her message was that CMS measurement rules, short pilot windows, and bureaucratic impatience prevented value-based payment success from being adequately recognized or scaled.

A Penn alum, Fowler is currently a Distinguished Scholar and faculty member at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and the Johns Hopkins Carey Business School. She is a veteran health policy architect whose career spans the Senate, the White House, and senior leadership roles across government and the private sector. Before her stint at CMMI, she was Chief Health Counsel to Senate Finance Committee Chairman Max Baucus, playing a central role in drafting the Senate framework for the Affordable Care Act. She later served as a special assistant to Barack Obama on health care and economic policy.

Created under the Affordable Care Act, CMMI sits within the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and is charged with testing new payment and service delivery models that aim to reduce costs while maintaining or improving quality — and scaling those that succeed as a new health care infrastructure. That authority has been central to advancing alternative payment models and accelerating Medicare and Medicaid’s shift away from pure fee-for-service toward value-based payment, alongside other ACA provisions and later legislation such as the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015, which explicitly sought to move Medicare toward value-based payment.

Fowler described CMMI’s first decade as “throwing spaghetti against the wall because we weren’t sure what worked,” with many pilots showing care improvements that were never allowed to mature. That problem has endured to the present.

She said the federal government lacks the patience required for long-term transformation, constantly judging programs before they have been given enough time to prove themselves. She described a recurring pattern observed during her time at CMMI: “I went to the sites and I saw the difference in care delivery and patient improvements … but then the model would end, and then two years later, an evaluation would come out and it would say, ‘Look, we were actually starting to make a difference — but the model was already gone.’”

She cited oncology, kidney care, and Accountable Health Communities pilots as examples where early gains appeared after CMS had already terminated the models.

A large part of the problem, she said, is structural and involves a government scoring system set up in a way that can make the success of a pilot almost impossible to prove. For example, she pointed to the Medicare Shared Savings Program, in which doctors and hospitals form an Accountable Care Organization value-based payment model. CMS sets an annual spending benchmark so that if the group spends less than that while successfully maintaining quality, partner providers receive a share of the savings.

But these value-based care programs were judged by accounting rules so strict that even successful efforts looked like failures. CMS counted savings shared with doctors as losses against the program’s original gains, wiping out most or all of those gains on paper — making it nearly impossible for a pilot to be formally recognized as a success.

“These were voluntary models for five years where you were making investments and hoping it paid off in five years — and the way the CMS actuary defines success, they were never going to reach that level,” Fowler said. “We were never able to dig out of that hole.”

Overall, she said CMMI’s value-based care transition has not reached its goals because of misaligned incentives, fragmentation, wary payers, and rules and practices that are out of sync with field reality. Beyond accounting barriers, she cited additional factors, including:

Turning to the future of health care, Fowler presented a worrisome picture.

“For anyone in the medical, health care, public health, research, and social services fields, this last year has been pretty challenging, the way it started off on a note of disruption and uncertainty,” Fowler said. “The Big Beautiful Bill is projected to take out $1 trillion from the Medicaid program, leading to potentially 10 million people becoming uninsured, plus another 4 million to 5 million potentially becoming uninsured due to expiration of ACA premium subsidies. We’ve never seen cuts like that before.”

Contrasting the current situation with the passage of the Medicare Modernization Act, which created Medicare Part D in 2003, and the ACA, which created the Health Insurance Marketplaces in 2010, Fowler recalled those periods as good-faith government and research efforts to define national problems and engage in reasonably bipartisan solutions.

Today, she said, the health system is subject to ongoing damage caused by policy uncertainty and political polarization. She described the current moment as one of “big ambition followed by instability,” arguing that major programs are repeatedly expanded and then partially dismantled depending on which party is in power. Such volatility, she said, undermines patients, providers, and long-term planning — especially in rural, underserved, and low-income communities.

“I think we need to get back to a place where we have a common diagnosis of the problem, and I think that simplifies down to affordability,” Fowler said. “Health care insurance is only affordable to those who don’t need health care. Employer insurance is $27,000 now, and people are still paying $7,000 out of pocket even if they have good insurance. That same affordability crisis is a problem for the nation’s public programs like Medicare, facing solvency pressures driven by high costs.”

But she said she remains optimistic.

“First, Medicaid is popular. It’s more popular than I think it ever was before. And what reaction to the One Big Beautiful Bill showed is that people can come together, because now a lot more people rely on the program and they don’t want to lose something.”

“I came to the Hill after the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 passed, and the cuts were so deep … what came next was a series of giveback bills, because the cuts had been made so deeply that there was an outcry and a revisiting of many policies,” said Fowler. “People gathered around and said that was too much, too deep … but they brought evidence, analysis, and credible voices.”

“I think some of that is going to happen as we go forward today, especially after the Medicaid cuts go into effect and so many people really start to lose their coverage,” she said.

A Major European–U.S. Hospital Study Finds That Changing How Hospitals Are Organized Reduces Burnout and Turnover While Improving Care Quality

Penn LDI Senior Fellow Dominic Sisti Cites “Alarming Levels”

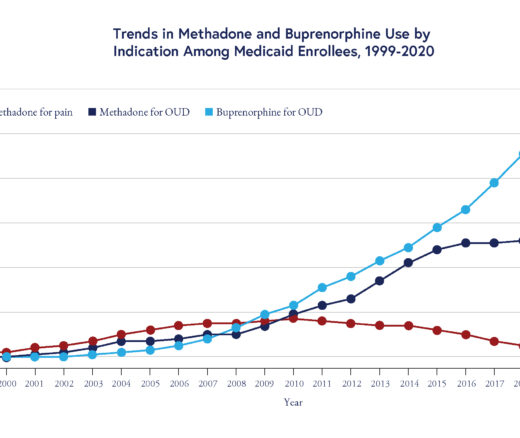

Chart of the Day: Methadone Use for Opioid Use Disorder Tripled From 2010–2020, Yet Only One in Four People With Addiction Receive Medication

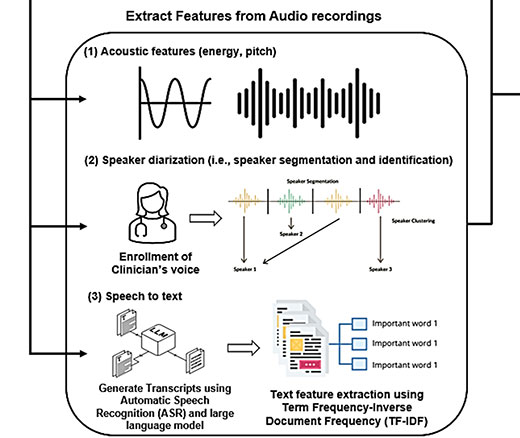

Researchers Use AI to Analyze Patient Phone Calls for Vocal Cues Predicting Palliative Care Acceptance

Medicare’s Payment Plan Can Ease Seniors’ Crushing Drug Costs but Medicare Buries it in the Fine Print

LDI Fellows’ Research Quantifies the Effects of High Health Care Costs for Consumers and Shines Light on Several Drivers of High U.S. Health Care Costs