Substance Use Disorder

Blog Post

Starting Opioid Use Disorder Treatment in the Emergency Department

Physician-reported barriers and facilitators

Every day, we hear about the staggering toll of the opioid overdose crisis. This is particularly salient in Philadelphia, which has one of the highest overdose death rates among major U.S. cities. Despite effective medications for opioid use disorder, such as buprenorphine and methadone, few people receive treatment. The ongoing challenge is to expand access to these lifesaving treatments to people who need them the most. Emergency departments, which treat patients 24/7 and provide an entry point into the health system, are a promising place to start.

We know medications work. One recent study showed that after a nonfatal overdose, methadone and buprenorphine treatment were associated with a 50% reduction in deaths in the following year. We know that starting buprenorphine in the emergency department works better than the typical practice of stabilizing and discharging a patient with a treatment referral, more than doubling the rate of treatment engagement at 30 days.

What we don’t know is how to apply these findings in real-world emergency departments, which are busy places navigating everything from the highest risk trauma patients to those with multiple chronic conditions and no primary care. With my colleagues Kit Delgado, Austin Kilaru, Jeanmarie Perrone, Zack Meisel, Jessica Hemmons, and Dina Abdel Rahman, I surveyed emergency medicine physicians in two Penn Medicine hospitals to understand the barriers and facilitators to starting buprenorphine in the emergency department.

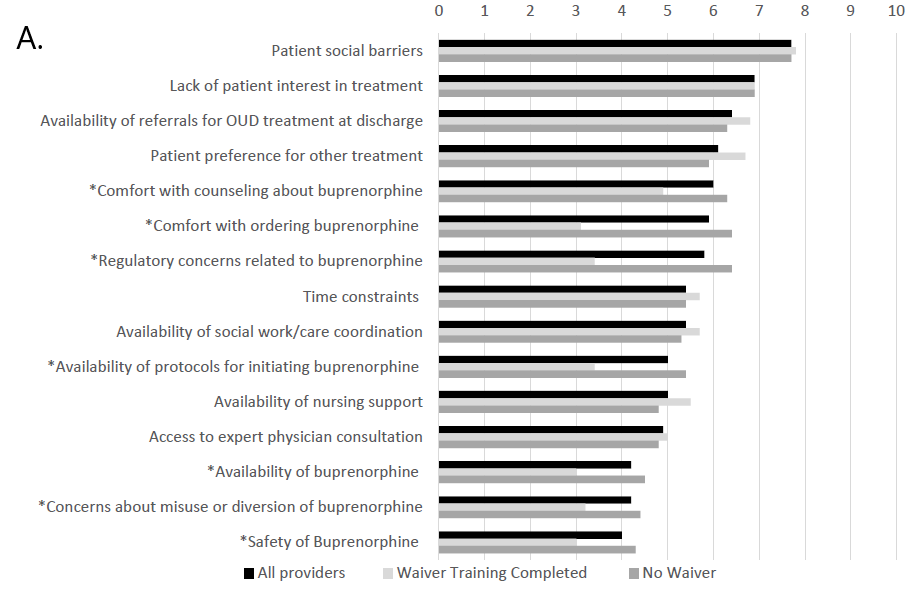

Some barriers were expected. For one, prescribing outside a hospital setting requires a Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 (DATA) waiver, better known as an X-waiver, which a physician can obtain after completing an 8-hour training course. More than half of the responding physicians who had completed an X-waiver training felt prepared to start patients on buprenorphine, compared with only 20% of those who had not done the training.

Surprisingly, the biggest barriers – patient social challenges, patient engagement in treatment, and availability of treatment referrals – were not related to medications. And these barriers did not differ between physicians with an X-waiver and those without. This suggest that efforts to increase the number of X-waivered physicians, though important, may not be enough to change practice.

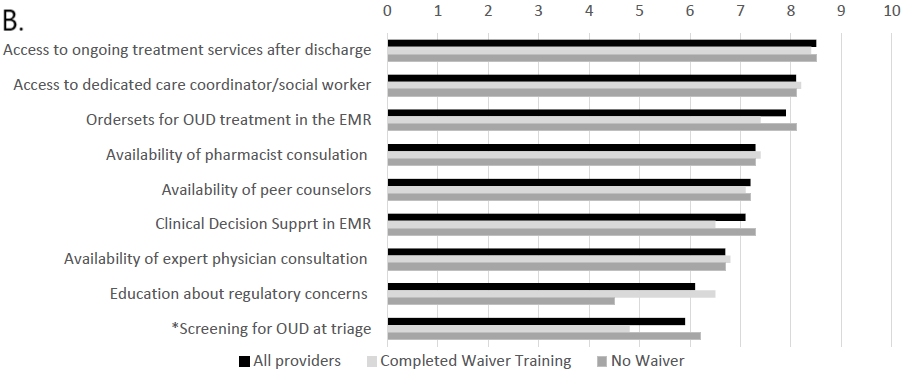

Physician ratings for barriers and facilitators to ordering buprenorphine in the emergency department. Barriers were rated on a scale from 1-10 (10 being the most significant barrier). Ratings are broken down by X-waiver status, and the asterisks indicate the responses that differed between the X-waiver trained and untrained groups.ion

Physicians in our study identified promising ways to help overcome these barriers. Some ideas include building in supports like social workers, care coordinators and certified recovery specialists – trained peers in recovery – to enhance the health care team’s ability to engage patients in treatment and link them to care after they leave the ED. While the literature on certified recovery specialists is still young, there is good reason to think that this is an effective strategy to engage patients. Peers in recovery already work in Penn Medicine EDs, clinics, and hospitals, and efforts are underway to expand their reach.

We also learned that for busy clinicians who had not yet attended waiver training, time is money. Physicians reported that time was their biggest barrier and favored financial incentives or replacement of a shift as the best way to promote waiver training. Behavioral incentives have helped to get about 75% of Penn Medicine ED physicians an x-waiver. Spearheaded by Jeanmarie Perrone, these efforts include weekly emails that share stories of Penn patients’ success on buprenorphine, nudging physicians to enroll in training.

Although incentives may be an important driver of practice change in supporting X-waiver training, this may be a costly investment from a health system or policy perspective. As others have argued, the most effective strategy may be to do away with the waiver system entirely. Buprenorphine is safer than traditional opioids and many other medications that do not require specialized training. X-waivers create barriers to prescribing that are counter-productive, particularly in the current opioid overdose crisis.

In the meantime, we are using the findings from our study to inform ongoing efforts in Penn Medicine hospitals. Our hope is that the emergency department can be a place where we can meet patients where they are and help them to begin their journey to recovery.

Margaret Lowenstein is a general internist and a National Clinician Scholar at Penn.