New Parents Put Infants’ Health First, While Their Own Suffers

Rural Parents Had More Emergency Visits and Insurance Loss Than Urban Peers, an LDI Study Shows. Integrated Baby Visits Could Help All Parents Be Healthier

Population Health

Blog Post

Over the past two decades, health care architects have rediscovered a forgotten but simple fact: Built environments affect the health and well-being of patients and staff. As a result, they have been designing institutions that provide opportunities to experience nature by incorporating “biophilic” design elements. These might be as simple as strategically placed potted plants that elevate mood and quell anxiety, or more grand atria and gardens that span indoor and outdoor spaces.

The Sheppard Pratt psychiatric hospital in Baltimore, MD is one such example. The institution was developed to provide mental and behavioral health care in a way that patients, staff, and visitors could cultivate connections with the community and “with the nearby hills, hollows, creeks, and wetlands.”

Wood battens frame the lobby walls, while ceilings in large spaces imitate a forest canopy. Windows allow sunlight to stream inside and provide views to courtyards and gardens. Sheppard Pratt President and CEO Harsh Trivedi, MD, MBA, states that their design goal was “to dispel every misconception of what a psychiatric hospital is.”

Nature-enriched institutional spaces are a far cry from the desolate images many Americans maintain of psychiatric institutions. Yet the movement toward biophilic design is taking hold. St. Elizabeths Hospital, a psychiatric hospital in Washington, D.C.—which was the setting of sociologist Erving Goffman’s classic book Asylums in which he analyzed how the dehumanization of patients unfolded in an oppressive and austere environment—now has incorporated evidence-based design principles to support healing and well-being of patients and staff.

In a recent article in the Harvard Review of Psychiatry, we, along with Stephanie Bi (Penn Psychiatry) and Philip Candilis (St. Elizabeths Hospital), explore the historical roots and contemporary practices of institutional designs that use access to “natural” spaces and elements to enhance patients’ health. We discuss how modern medical practice has ignored the ethical dimensions of health care architecture to the detriment of patient well-being. We explore institutional design in the centuries before 1900 to show how mental health administrators embraced moral architecture and the provision of access to health-promoting spaces, including airing courts, gardens, outdoor amusements, and light-filled rooms.

Many mental health institutions shuttered in the second half of the 20th century; the result of changes in psychiatric medical practice and theory, and the subsequent awakening to the abuses and mistreatment that too many patients endured. These closures show that architecture alone is not enough to provide patients with high-level care, we must continuously evaluate and improve based on changing needs and circumstances.

The demand for mental health care and services has increased substantially over the past several decades, and our current treatment modalities have lagged. One way to catch up is to refocus our attention on the growing evidence demonstrating patients’ environments can enhance (or impair) health and healing.

More specifically, we recommend policy reforms across a range of design choices:

We acknowledge that such changes won’t be easy; they demand a shift in thinking from risk management to prioritizing health and well-being. However, these are not mutually exclusive goals, as institutions like St. Elizabeths and Sheppard Pratt have shown.

Ultimately we believe health care architectural and design decisions are ethical choices. Health care designers, practitioners, and policymakers should aim to create biophilic clinical spaces that enhance patients’ potential of recovery and healing, while also reducing clinician stress and burnout.

We encourage policymakers, payers, and clinicians to recognize the built environment as a health care intervention itself, recognizing it as a means of providing holistic, compassionate care.

The study, “Psychiatric Hospitals and the Ethics of Salutogenic Design: The Return of Moral Architecture?,” was published in July 2024 in the Harvard Review of Psychiatry. Authors include Meghan Crnic, Stephanie Bi, Philip J Candilis, and Dominic Sisti.

Rural Parents Had More Emergency Visits and Insurance Loss Than Urban Peers, an LDI Study Shows. Integrated Baby Visits Could Help All Parents Be Healthier

From Anxiety and Loneliness to Obesity and Gun Deaths, a Sweeping New Study Uncovers a Devastating Decline in the Health and Well-Being of U.S. Children

Before Lawmakers Do Full Legalization, We Must Face the Reality: High-Potency Marijuana Already Harms Kids and Adults Alike

Just Discussing Punitive or Supportive Policies—Even Before They’re Enacted—Can Impact Physical and Mental Health, Especially for Marginalized Groups, LDI Fellow Says

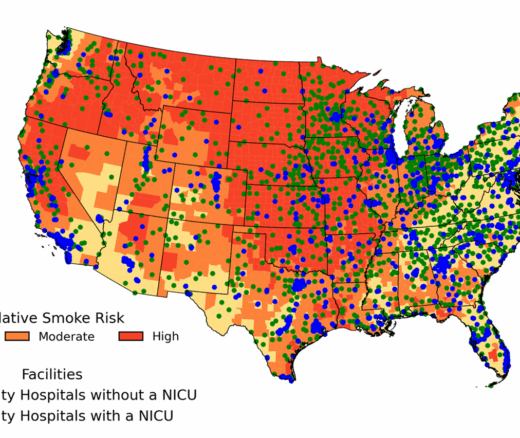

Chart of the Day: New Study Maps Maternity Care Gaps in Smoke-Prone U.S. Counties

But Many Other Factors Played a Role in Denying Loans, LDI Fellow Says