Brief

Changes to Racial Disparities in Readmission Rates After Medicare’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program Within Safety-Net and Non-Safety-Net Hospitals

Hospital-based financial incentives may exacerbate disparities

Krisda H. Chaiyachati, Mingyu Qi, Rachel M. Werner

JAMA Network Open – published November 2, 2018

Key Findings

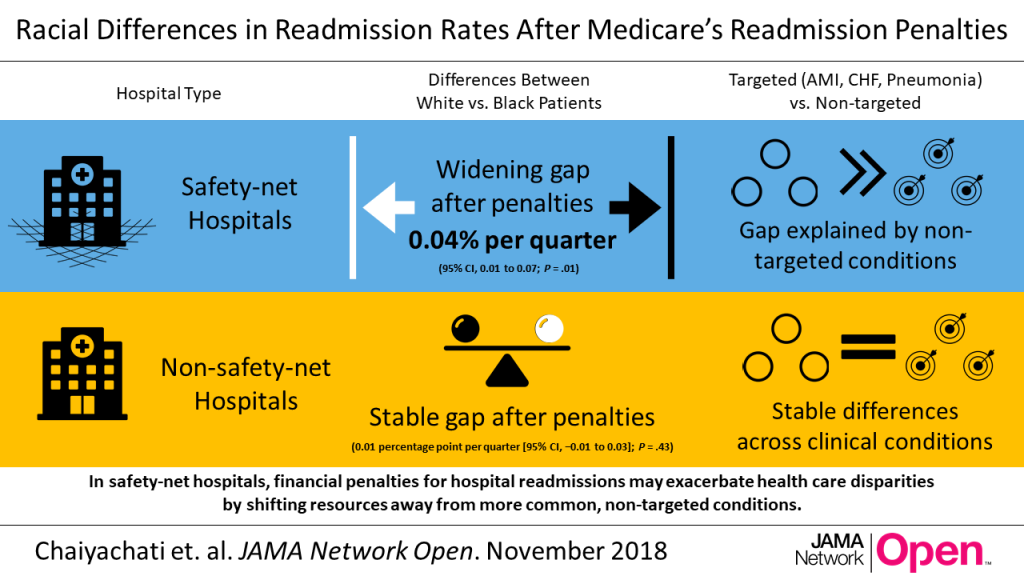

After the Medicare Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program began enforcing financial penalties, disparities in readmissions between white and black patients widened at safety-net hospitals for conditions not targeted by the program. Disparities were stable for conditions targeted by the program. At non-safety-net hospitals, disparities were unchanged for both targeted and non-targeted conditions.

The Question

Medicare’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) financially penalizes hospitals with higher-than-expected 30-day readmission rates for select clinical conditions (acute myocardial infarction, pneumonia, and heart failure). Since its implementation, readmission rates have declined for the HRRP-targeted conditions, and to a lesser degree, for non-targeted conditions. There are, however, concerns that the program could exacerbate health care disparities by harming “safety-net hospitals” – institutions that disproportionately serve minority patients.

This analysis looks across three time periods: 2007-2010, prior to the Affordable Care Act (ACA); 2010-2012, during HRRP implementation; and, 2012-2015, after the HRRP enforced penalties. It evaluates how readmission disparities between black and white patients changed within safety-net and non-safety-net hospitals after the HRRP began enforcing financial penalties, and how these trends differed for conditions targeted and not targeted by HRRP penalties.

The Findings

During the implementation phase of the HRRP, disparities in readmission rates were improving within both safety-net and non-safety-net hospitals, irrespective of the clinical condition. After the enforcement of the HRRP penalties, disparities in readmission rates widened within safety-net hospitals, specifically for conditions not targeted by HRRP penalties.

Comparing safety-net and non-safety-net hospitals

Before the ACA (2007-2010), white and black patients discharged from safety-net hospitals had relatively higher risk-adjusted readmission rates than those from non-safety-net hospitals. The racial disparity remained stable during this time, in both safety-net and non-safety net hospitals.

Overall, readmission rates for black and white patients across safety-net and non-safety-net hospitals declined during HRRP’s implementation (2010-2012). In safety-net hospitals, black patients had a steeper decline in readmission rates than white patients, resulting in a slight narrowing of disparities in readmission rates. Non-safety-net hospitals also saw a narrowing of disparities in readmission rates during this time, but at an even smaller magnitude.

Readmissions disparities stopped improving during the HRRP penalty period (2012-2015). During this time, readmission disparities widened in safety-net hospitals (0.04 percentage point per quarter), whereas they remained stable in non-safety-net hospitals.

Changes in readmission disparities for targeted and non-targeted conditions

During the pre-ACA and HRRP implementation periods, the observed trends in black and white readmissions did not differ for HRRP-targeted conditions and non-targeted conditions in either safety-net or non-safety-net hospitals.

However, when the authors compared readmissions by condition during the HRRP penalty period, readmission disparities widened (0.05 percentage point per quarter) within safety-net hospitals for conditions not targeted by the HRRP, while disparities for HRRP-targeted conditions did not change. Readmission disparities were stable for both targeted and non-targeted conditions in non-safety-net hospitals during this period.

The Implications

This study shows that hospital-based financial incentives may exacerbate health care disparities. It highlights how financial penalties for hospital readmissions have potential consequences for conditions not targeted by the penalties, and that safety-net hospitals are particularly sensitive to this risk. The findings suggest that when readmission penalties target certain clinical conditions, scarce resources could shift away from other operational objectives and affect quality for non-targeted conditions.

Although the increases in racial disparities in hospital readmission rates observed in this study are relatively modest, conditions not targeted by the HRRP represent six times more discharges than targeted conditions (86.5 percent vs. 13.5 percent). This means that even small increases in disparities could have consequences for a larger portion of the population.

The HRRP has reduced Medicare payments to safety-net hospitals by one to three percent. If payments are reduced, safety-net hospitals have less revenue to invest in quality-improvement programs, thus potentially widening existing disparities. These findings point to the HRRP’s potential longer-term consequences on readmission disparities between white and black patients, especially for those served by safety-net hospitals.

Reducing disparities in readmission rates will require an understanding of hospital strategies that lead to persistent reductions among vulnerable populations. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the National Quality Forum are considering hospital-wide readmission measures, which may help to mitigate differences in trends by clinical condition. However, these programs may impose higher penalties on more hospitals, penalties to which safety-net hospitals are already particularly sensitive.

The Study

This study looked at nearly 60 million discharges of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries with any clinical condition from 3,871 acute-care hospitals between January 1, 2007 and September 30, 2015. About one fifth of discharges were from safety-net hospitals, defined as the those with the highest proportion of Medicaid discharges in each state.

The analysis relies on three data sources: (1) Medicare Provider Analysis and Review files and the Medicare Beneficiary Summary File, which include data on demographics and enrollment, and hospital claims for fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries; (2) Medicare Provider of Services files, which include hospital characteristics; (3) the American Hospital Association Annual Survey of Hospitals, which includes data on Medicaid discharges at each hospital. All estimates were adjusted for patient and hospital characteristics.

The authors were primarily interested in whether a patient had an unplanned readmission within 30 days of hospital discharge. They assessed the patient’s race (white or black), the quarter in which the patient was discharged, the clinical condition, and whether or not the discharging hospital was a safety-net hospital. They measured changes in disparities in safety-net and non–safety-net hospitals after the HRRP penalties were enforced and compared with prior trends.

Lead Author: Dr. Krisda Chaiyachati

Krisda Chaiyachati, MD, MPH, MSHP, is an Assistant Professor of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. He designs, studies, and implements innovative strategies for improving health care accessibility, addressing social barriers to care, and managing population health goals. His research seeks to understand how to improve health outcomes for low-income and minority populations.