Brief

Networks in ACA Marketplaces are Narrower for Mental Health Care Than for Primary Care

Raises Parity Concerns

Jane M. Zhu, Yuehan Zhang, Daniel E. Polsky: Health Affairs, September 2017

Key Findings

In 2016, ACA marketplace plans offered provider networks that were far narrower for mental health care than for primary care. On average, plan networks included 24 percent of all primary care providers and 11 percent of all mental health care providers in a given market. Just 43 percent of psychiatrists and 19 percent of nonphysician mental health providers participate in any network. These findings raise important questions about network sufficiency, consumer choice, and access to mental health care in marketplace plans.

The Question

Forming networks of low-cost providers is one way that insurers can control costs and offer lower premiums in ACA marketplace plans. Nearly half of plans offer “narrow” networks, generally defined as networks with less than 25 percent of providers in a given market. Networks that are too narrow, however, may jeopardize access to primary or specialty care. This is particularly true in mental health care, where many providers did not participate in any insurance networks before the ACA.

Thus, the authors sought to answer two questions: first, how mental health care providers compare to primary care providers in terms of their participation in ACA networks and the size of the networks they are in; and second, in the context of efforts to achieve parity between mental health care and general medical care, the extent to which parity in network size exists. The study looked at both physicians and nonphysician providers.

The Findings

The study identified 531 unique provider networks offered by 281 different insurers on the marketplaces. It analyzed data from 535,114 primary care providers [52 percent physicians, 48 percent nurse practitioners (NPs) or physician assistants (PAs)] and 562,379 mental health care providers (9.2 percent psychiatrists, 18.4 percent psychologists, 71.2 percent nonphysician behavioral specialists, counselors, or therapists; 1.3 percent NPs or PAs).

Network size. Mental health care networks were more narrow than primary care networks. For example, 57.4 percent of plans had narrow networks of psychiatrists, compared to 38.7 percent of plans with narrow networks for primary care physicians. The difference holds for networks of nonphysician providers as well, where nearly 90 percent of plans had narrow networks of mental health care practitioners, compared to about 75 percent of plans with narrow networks for primary care practitioners.

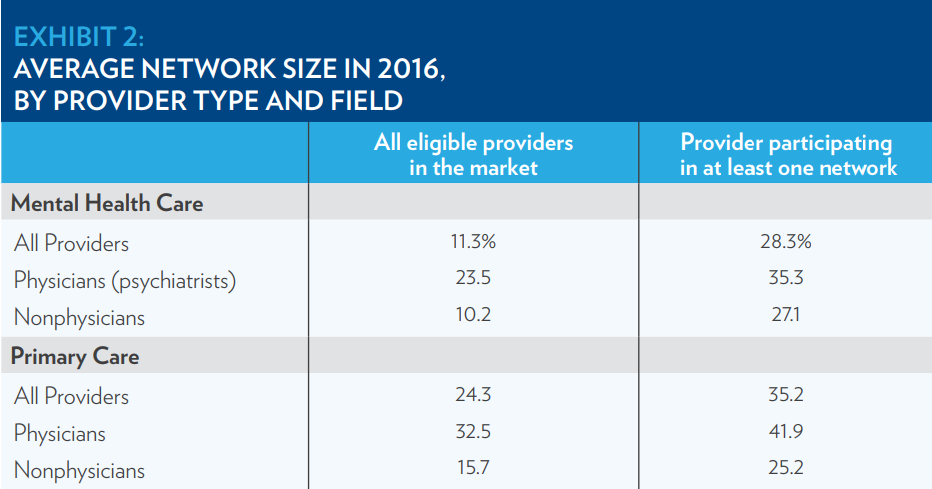

On average, plan networks included only 11.3 percent of all mental health care providers and 24.3 percent of all primary care providers in a given market.

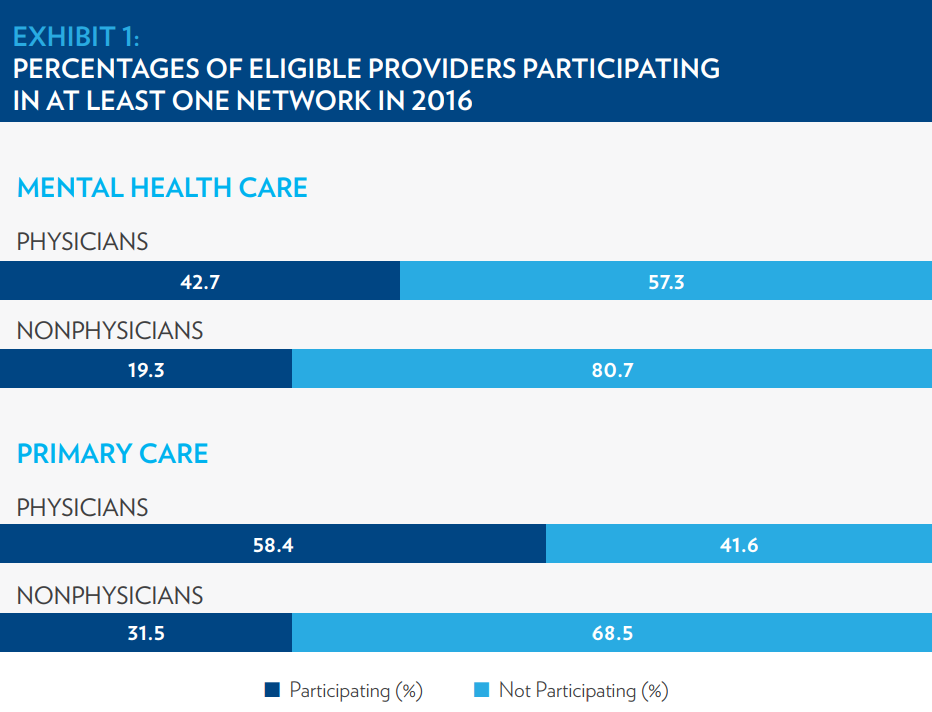

Network participation. Overall, 21.4 percent of mental health care providers and 45.6 percent of primary care providers participated in at least one network in their county. Participation was significantly different by specialty and by provider type (Exhibit 1). Specifically, 42.7 percent of psychiatrists participated in at least one network, compared to 58.4 percent of primary care physicians, a difference of 15.7 percentage points. Nonphysician providers had even lower participation; for example, just 19.3 percent of nonphysician mental health care providers were in any network (23.4 percentage points lower than psychiatrists.

To explore whether provider participation in networks could explain differences in network size, the authors looked at the subset of providers that participated in at least one network (Exhibit 2). In this subset, specialty differences decreased: the average network included 28.3 percent of participating mental health providers and 35.2 percent of participating primary care providers. This suggests that much of the narrowness of mental health care networks is due to low provider participation.

Parity. The authors found little correlation in network size for different specialties. Plans with broader networks of primary care providers did not necessarily have larger networks for mental health care providers. There was little parity in network size, with most plans having larger networks for primary care than for mental health care.

The Implications

This study highlights important structural barriers to adequate access to mental health care and parity with general medical care in marketplace plans. Mental health care is one of the ten “essential benefits” that must be offered in ACA plans, but network participation among mental health care providers remains low. This contributes to the narrowness of mental health networks and may undermine the ability of both federal parity laws, such as the 2008 Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, and the ACA to guarantee access to mental health care.

Previous research found that psychiatrists are the least likely physicians to accept Medicaid, Medicare, and commercial insurance, and therefore to participate in provider networks. Because of high demand for mental health services, psychiatrists have market power to choose not to participate in networks that reimburse them at low rates for time-intensive services. Improving consumer choice, therefore, will require provider interventions that tackle inadequate reimbursement rates, address the administrative burden of managed care, and relieve workforce shortages. There is a need to expand network participation among high-quality, lower-cost nonphysician mental health providers to supplement or substitute for some care usually provided by psychiatrists.

Furthermore, the authors’ findings of broader primary care networks and higher primary care provider participation suggest an important supplementary access point for mental health care. As primary care physicians provide more mental health services, implementing more effective models of collaboration between primary care providers and mental health care providers becomes critical.

These findings suggest that the use of narrow networks could exacerbate existing challenges in meeting mental health care demands. In response, federal and state policy should clarify network adequacy standards to assure mental health care parity and reasonable access to care.

The Study

The authors compared mental health and primary care providers in 2016 ACA plan using plan, network, and provider level data. They obtained a list of providers participating in each network from Vericred, a company that maintains complete provider-network data. Provider characteristics such as specialty and type were obtained from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and plan characteristics such service area were obtained from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Health Insurance Exchange data set. They identified 531 unique provider networks offered by 281 different insurers, representing a nearly complete picture of plans on the ACA marketplaces.

The mental health provider group included psychiatrists and nonphysician mental health specialists such as psychologists, specialized NPs and PAs, and other behavioral specialists, counselors, and therapists with masters or doctoral degrees. The primary care provider group included physicians with a primary care internal medicine specialty, and nonphysicians such as NPs and PAs.

Eligible providers for a network practiced in a county where a plan associated with the network was sold. Participating providers were those assigned to at least one plan network offered in the marketplaces. Network size was estimated by the ratio of the number of providers participating in each network to the total number of providers eligible for network participation in each state, and by the ratio of the number of providers participating in each network to the total number of providers participating in at least one network in each state. The authors also categorized network size with consumer-friendly groupings used in prior studies. Specifically, “narrow” networks were defined as including fewer than 25 percent of total providers in the state.

Study limitations included the absence of social workers in the dataset, and incomplete information on behavioral health carve-outs, which use specialized management firms to deliver mental health care to enrollees. These may result in under-reporting of mental health care providers.

Lead Author

Jane M. Zhu, MD, MPP, is a practicing internist, a 2016-2018 National Clinician Scholar, and an associate fellow at the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania. She is interested in how reforms in delivery systems organization, health insurance, and provider payment affect access to and quality of care, particularly in chronic disease management and mental/behavioral health. She received her undergraduate degree at Duke University, and obtained dual degrees in medicine and public policy from Harvard Medical School and the Harvard Kennedy School of Government. She completed her residency training in internal medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.