Can AI Hear When Patients Are Ready for Palliative Care?

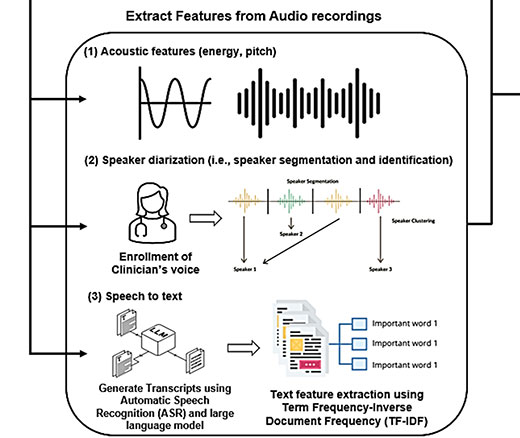

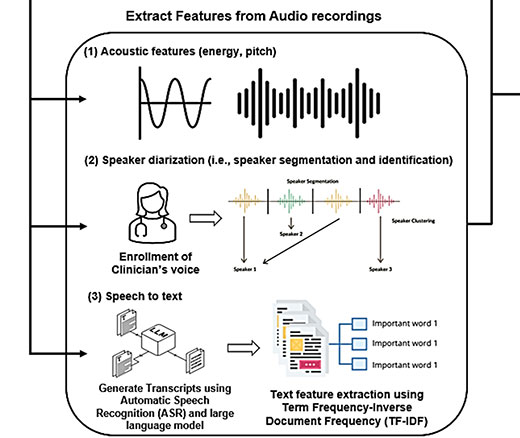

Researchers Use AI to Analyze Patient Phone Calls for Vocal Cues Predicting Palliative Care Acceptance

Blog Post

Follow the money is time-honored advice for journalists. Two LDI Fellows recently took that adage to heart, conducting the first comprehensive analysis of industry payments to doctors who use AI-powered medical devices.

Companies paid nearly $60 million to 46,000 doctors for AI-enabled devices from 2017 to 2023, according to the study by LDI Fellows Alon Bergman and Kaustav Shah in Health Affairs Scholar. The biggest recipients were cardiologists, but brain surgeons and radiologists were also in the mix.

The payments favored doctors at well-endowed academic hospitals, suggesting that artificial intelligence may not spread evenly to under-resourced hospitals in rural and urban areas.

A few firms also dominated the spending, raising concerns about market domination. The Johnson & Johnson unit Biosense Webster accounted for 82.5% of payments in cardiac electrophysiology, which focuses on the heart’s electrical systems. Device giant Medtronic distributed its payments around several specialties ranging from neurosurgery (23.1% share) to orthopedic surgery (18.5%).

Payments to doctors have long been a practice used to develop new technology and spread it to hospitals and beyond. However, doctors are more likely to use devices from manufacturers who pay them, studies show. Devices with artificial intelligence raise deeper concerns for their opaque operations, evolving effects, and lack of oversight.

FDA-approved AI devices are surging in popularity. By mid-2025, over 1,200 AI-enabled devices had received Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s stamp of approval, representing a 350% rise in clearances over five years.

But that regulatory process is full of gaps. Most devices have been cleared through the FDA’s 510(k) pathway, which requires manufacturers to show only substantial equivalence to a previous product that often lacked AI and was used for different purposes.

In addition, many AI tools now bypass FDA reviews altogether — such as AI scribes that record medical encounters — because they aren’t considered medical devices.

The authors call for reimagining the FDA approval process to recognize that AI-enabled devices continue to learn and adapt and must be regulated differently from earlier products.

We also need to send funds and infrastructure to help weaker rural and urban hospitals to adopt AI medical devices, the authors say. Health systems that lack their own robust evaluation capabilities may become even more reliant on vendors when making purchasing decisions.

“We’re laying the groundwork for how AI will function in medicine,” Bergman said, “How it’s built will determine whether AI closes gaps in care or widens them.”

For more, read Shah’s comments below:

Shah: AI medical devices are becoming more common in all healthcare settings. The FDA publishes a list of devices approved that have an AI/ML component and we have seen this grow from < 10 for the early 2010s, to over 200 last year. These devices are most commonly in radiology. We don’t have a good sense of how often these devices are being used in day-to-day clinical practice. Importantly, many AI tools in healthcare that are widely known and used– for example ambient technology like AI scribes — have no FDA review because they are not classified as medical devices.

Shah: Tracking day-to-day clinical usage is difficult since a lot of these devices don’t have a reimbursable code that can be easily tracked through medical claims, and we have seen so much growth over the past year. With those caveats, we have seen that larger, academic hospitals typically located in non-rural and higher-income areas have reported more use of AI devices and other predictive AI tools.

Shah: Most devices have been cleared through the FDA’s 510(k) pathway – this requires proving a new device is similar to a previously approved or predicate device. Other researchers have shown these predicate devices often do not use AI, do not have robust patient data in their training set, and have limited to no trial data proving their effectiveness.

Shah: I am a physician and focus on how health systems adopt and govern new digital technologies. Alon is an expert in medical devices and industry partnerships. We had a shared interest as we saw the emergence of AI medical devices and wanted to tell the story of industry-physician partnerships in this new space.

Shah: First, there is a large volume of payments going from AI device vendors – nearly $60M between 2017 and 2023 and the share of overall device payments from AI devices nearly doubled. Most of the payments are in radiology, heart (cardiology), and brain (neurology and neurosurgery), which makes sense since these fields have a lot of imaging and physiological data. General medical device payments are often made to procedural specialties, and some fields — general and orthopedic surgery — don’t have high AI payments yet despite high general payments. We also see that payments are flowing to physicians that work at larger, urban, teaching hospitals. These are hospitals that tend to be on the leading edge of research and development and use more AI in clinical care.

Shah: As I mentioned before, many of AI services physicians and patients are used to –ambient scribing, automated responses to patient messages — are not currently evaluated by the FDA and are not included in this analysis. Next, the physician analysis focuses only on those parts of the Medicare program, which is most but not all physicians. Most importantly, we don’t know how the industry relationships impacted clinical use of the AI medical devices.

Shah: First, transparent reporting of industry relationships is important for both device makers and clinicians. Next, strengthening or re-imagining the FDA approval process for AI medical devices is important – the underlying architecture that powers these devices is different from a traditional device and so proving quality and safety requires a different style of evaluation. Lastly, as these devices become more common and improve in quality, targeted funding and infrastructure will be needed to help smaller, rural hospitals adopt and implement AI medical devices.

Shah: We are hoping to study clinical usage of AI medical devices and see if we can link industry relationships to changes in practice patterns.

The study, “Characterizing Industry Payments for FDA-Approved AI Medical Devices,” was published in Health Affairs Scholar on November 10, 2025. Authors include Alon Bergman, Tej A. Patel, and Kaustav P. Shah.

Researchers Use AI to Analyze Patient Phone Calls for Vocal Cues Predicting Palliative Care Acceptance

A Licensure Model May Offer Safer Oversight as Clinical AI Grows More Complex, a Penn LDI Doctor Says

Study of Six Large Language Models Found Big Differences in Responses to Clinical Scenarios

Experts at Penn LDI Panel Call for Rapid Training of Students and Faculty

One of the Authors, Penn’s Kevin B. Johnson, Explains the Principles It Sets Out

More Focused and Comprehensive Large Language Model Chatbots Envisioned