Health Care Access & Coverage

Blog Post

Addressing Out-Of-Pocket Specialty Drug Costs In Medicare Part D: The Good, The Bad, The Ugly, And The Ignored

A Health Affairs blog

[Reposted: Jalpa A. Doshi, Amy R. Pettit, and Pengxiang Li. Addressing Out-Of-Pocket Specialty Drug Costs In Medicare Part D: The Good, The Bad, The Ugly, And The Ignored, Health Affairs Blog, July 25, 2018. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20180724.734269/full/: Copyright ©2018 Health Affairs by Project HOPE – The People-to-People Health Foundation, Inc.]

The cost of prescription drugs in the United States has been a popular topic of debate in recent years, particularly when it comes to specialty drugs with very high price tags. High-profile proposals and reports—including this year’s President’s Budget; the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine’s report on making medicines affordable; the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) annual report to Congress; and the recent Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Blueprint to Lower Drug Prices and Out-of-Pocket Costs—have made a variety of recommendations, leading to a flurry of reactions from all segments of the health care industry.

But how would these recommendations directly or indirectly affect out-of-pocket costs for elderly and disabled individuals who are actually taking the most expensive medications? The combination of high drug prices and cost-sharing requirements under Medicare Part D’s current benefit structure results in a high out-of-pocket burden for patients needing specialty drugs. Our research offers insights into how key recommendations would alleviate some burdens, intensify others, and fail to address additional concerns. In particular, many proposals to date have omitted a critical issue: It’s not just how much Medicare Part D patients are asked to pay out of pocket in a given year, but when they are required to pay it.

Specialty Drugs And Cost Sharing: Promise And Perils

Specialty drugs typically offer major treatment advances for patients with serious, chronic, or life-threatening diseases for whom prior treatments were ineffective, highly toxic, or previously unavailable. Many have been shown to reduce the risk of disease progression or costly complications for chronic diseases or to improve survival for life-threatening conditions.

Until recently, there was a serious gap in knowledge regarding how out-of-pocket costs under Medicare Part D impact specialty drug utilization. A series of recent studies, including several published by our team, have found that higher out-of-pocket costs under current Medicare Part D policies are associated with markedly higher rates of abandonment of new specialty drug prescriptions; reductions and delays in treatment initiation following a new diagnosis or disease progression; delays between refills or treatment interruptions; and earlier discontinuation of treatment. These patterns are consistent across each of the disease areas we have examined, including multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and a variety of cancers such as chronic myeloid leukemia and metastatic renal cell carcinoma.

The Current Rollercoaster

Any proposed changes must be evaluated in the context of the current standard Part D benefit design, which has variable cost-sharing requirements across the coverage year. Patients who are not eligible for low-income subsidies are subject to a deductible (up to $405 in 2018), followed by an initial coverage phase with 25 percent coinsurance. However, Part D plans may place drugs costing $670 or more per month on a “specialty tier,” where they may be subject to up to 33 percent coinsurance during this phase. Virtually all plans now have a specialty tier. Unlike copayments of a fixed dollar amount, coinsurance payments vary based on the list price of the medication.

Once total (patient plus plan) prescription spending hits an initial coverage limit ($3,750 in 2018), beneficiaries enter a coverage gap, or “donut hole” phase. Whereas beneficiaries were originally responsible for 100 percent of their drug costs during this phase, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has gradually reduced this obligation by requiring manufacturers to provide a discount on brand-name medications. Today, beneficiaries pay 35 percent coinsurance for brand-name medications during the donut hole; the recent Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 will further reduce this to 25 percent beginning in 2019.

During the coverage gap, manufacturer discounts are credited toward patients’ true out-of-pocket costs (TrOOP). Once this combined TrOOP spending reaches a catastrophic coverage limit ($5,000 in 2018), beneficiaries are required to pay 5 percent coinsurance for the remainder of the coverage year. The annual benefit resets on January 1 of the following year, and the cycle begins again.

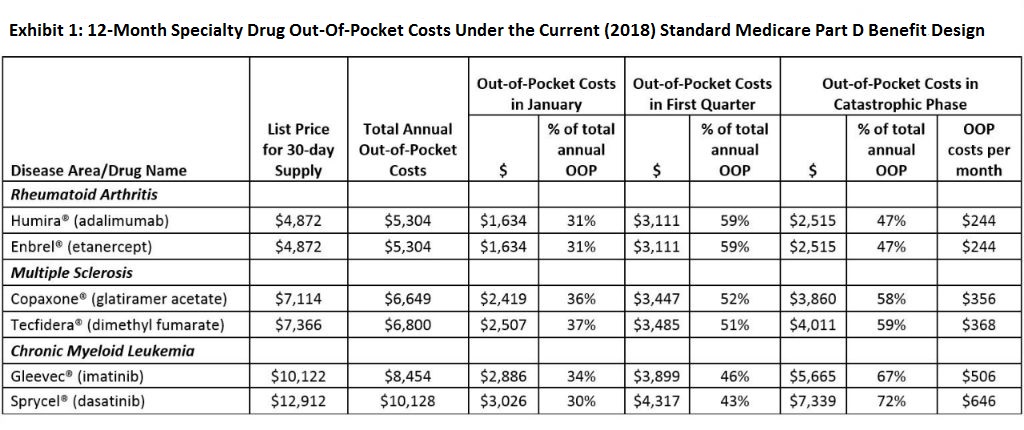

We examined what a variety of specific recommendations in recent high-profile proposals might mean for Part D patients needing specialty drugs. To illustrate anticipated impact, we applied the 2018 standard Part D benefit design and calculated patient out-of-pocket costs for the two most frequently used Part D drugs in three of the top specialty drug disease areas: rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and chronic myeloid leukemia, a type of cancer where treatment has the ability to restore near-normal life expectancy (see Exhibit 1).

The Good

Introduction Of An Annual Out-Of-Pocket Maximum

The Medicare population is the only insured segment of the US health care system that is not protected by a cap on annual out-of-pocket spending. (Even ACA health insurance exchange plans, which offer varying levels of coverage, have this protection.) Most high-profile proposals recommend converting the catastrophic coverage limit into an out-of-pocket maximum, eliminating 5 percent cost sharing during the catastrophic coverage phase.

This recommendation has been widely praised, and as we have shown previously, it would indeed offer meaningful relief for many patients taking specialty drugs. For example, this year patients with rheumatoid arthritis taking one of the two most frequently used specialty drugs would face cumulative 12-month Part D out-of-pocket costs of $5,304 for that medication alone, 47 percent of which occurs after reaching the catastrophic coverage limit. Patients with multiple sclerosis currently face $6,649–$6,800 in annual out-of-pocket costs (nearly 60 percent during catastrophic coverage), and those with chronic myeloid leukemia pay $8,454–$10,128 annually (67–72 percent during catastrophic coverage) (see Exhibit 1). Even 5 percent cost sharing in the catastrophic coverage phase results in out-of-pocket payments of $244 to $646 per monthly prescription for these patients.

Action On Biosimilars And Generics

Several proposals have recommended easing the way for introduction of new and presumably less expensive generic versions of brand-name drugs as well as biosimilars, which are considered to be interchangeable with branded biologic specialty drugs. MedPAC has also recommended that the 50 percent manufacturer discounts currently applied only to brand-name drugs during the donut hole be extended to include biosimilars. This is a positive step. Patients using (or switching to) a biosimilar would pay the coinsurance on a lower list price while also continuing to benefit from the lower cost share during the donut hole.

However, these changes will not be revolutionary: Unlike generics for traditional drugs, which can cost a small fraction of the brand-name price, biosimilars (and generics for non-biologic specialty drugs) still have substantial price tags and may face multiple barriers to uptake. Prior projections of the short- to mid-term savings from biosimilars arrived at a reduction in drug price of 10–50 percent, as opposed to the typical 80–85 percent reduction in generic versions of traditional brand-name drugs. For instance, if a biosimilar for Humira® were to be introduced to the US market at a price 25 percent below the current brand-name list price, 12-month out-of-pocket costs for a patient with rheumatoid arthritis switching to the biosimilar would drop only 14 percent (from $5,304 to $4,573) under the 2018 Part D cost-sharing structure.

Passing On Rebates To Consumers

Under current practice, manufacturers offer significant rebates to Part D plan sponsors for certain specialty drugs, with the savings theoretically passed on to all consumers via lower premiums. However, patients still pay their coinsurance liabilities under Part D as a percentage of the original list price, so this system of rebates may actually increase beneficiaries’ out-of-pockets costs (and federal spending) under Part D.

Most high-profile proposals have recommended changes that would require Medicare Part D plans to apply a substantial portion of these rebates to help consumers at the point of sale, directly lowering out-of-pocket costs at the pharmacy counter. In cases where rebates are common, such as for large-volume specialty drugs for rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis, this should help reduce out-of-pocket burden. Unfortunately, this benefit will not be universal: Some specialty drug classes, particularly small-volume drugs such as those for specific cancers or drugs that face limited competition, are not typically subject to rebates, and classes with less competition tend to be significantly higher-priced.

Information on rebates is proprietary, making predictions difficult. Yet, even if we were to assume that a 25 percent rebate on a high-volume specialty drug such as Humira® were passed on to patients, their 12-month out-of-pocket costs would drop by only $731 (approximately 14 percent), comparable to the price reduction in the biosimilar example above.

Tying Cost Sharing To Value

Currently, cost sharing for specialty drugs under the Part D benefit is directly tied to the cost (list price) of the drug, regardless of its clinical benefit. The National Academies report, in particular, emphasized the importance of moving toward a system that determines cost-sharing rates in a way that “include[s] the costs and clinical effectiveness of prescription drugs.”

This shift away from relying solely on the cost of the drug to determine cost sharing is promising. We have previously recommended, as have others, that the widely used value-based insurance design approach that lowers out-of-pocket costs for evidence-based traditional medications (for example, antihypertensives, antidiabetic agents) be extended to Medicare Part D specialty drugs that offer high value. Depending on how much plans are willing to lower out-of-pocket costs for high-value specialty drugs, this approach could possibly lead to sizeable reductions in out-of-pocket burden.

The Bad

Eliminating Manufacturer Discounts From TrOOP Calculations

In an effort to contain overall Medicare Part D program spending, MedPAC and the President’s Budget have recommended discontinuing the policy of counting the 50 percent manufacturer discount toward calculation of beneficiaries’ TrOOP spending during the donut hole. As discussed in a prior Health Affairs Blog post, this change would effectively extend the time patients spend in the coverage gap, increasing the amount they must spend out-of-pocket before reaching catastrophic coverage and potentially increasing the risk of cost-related discontinuation during this coverage phase.

From our perspective, this proposed change is akin to the “copay accumulator” programs recently introduced by several payers to counteract manufacturer coupon programs in the commercially insured population; it exacerbates the out-of-pocket burden on patients needing expensive specialty drug medications. If this change were implemented without the proposed annual out-of-pocket maximum, then patients using specialty drugs would face an increase of up to $1,895 in their 12-month out-of-pocket costs (under the 2018 benefit design). If combined with an annual out-of-pocket maximum, then overall out-of-pocket costs would go down, but patients would face substantially higher monthly out-of-pocket costs at the beginning of the year (see “The Ignored” section below).

The Ugly

Shifting Part B Drugs To Part D

Under current policy, medications such as infused chemotherapies that are administered by, or under supervision of, a physician are typically covered by Medicare Part B (medical benefit). Since the federal government is unable to negotiate drug prices on behalf of Medicare, recent proposals, including the HHS Blueprint, have raised the possibility of transferring certain Part B drug classes to Part D, with the goal of empowering insurers and pharmacy benefit managers to negotiate better prices.

This proposed strategy overlooks key elements of Medicare coverage. Medicare covers 80 percent of the costs of Part B drugs, with patients responsible for the remaining 20 percent in the form of coinsurance. However, the vast majority of patients have supplemental insurance (that is, Medigap plans, employer-sponsored retiree coverage) that cover this coinsurance obligation, meaning patients actually face minimal or no out-of-pocket costs for Part B drugs. Prior research has shown that Part D patients not receiving low-income subsidies face financial barriers to Part D specialty drugs and opt for Part B specialty drug alternatives (if available), given the minimal or zero out-of-pocket costs.

Thus, even if payers were to succeed in negotiating comparatively lower prices for certain specialty drug classes, moving coverage to Part D would subject patients to dramatically higher out-of-pocket costs since Medicare supplemental insurance plans are not permitted to pay for Part D cost sharing under current law.

The Ignored

Timing Of Out-Of-Pocket Costs

All major proposals fail to address a key liability of the current Part D benefit structure: Out-of-pocket costs spike at the beginning of each calendar year. The more expensive the drug, the faster beneficiaries move through cost-sharing phases, and the more front-loaded their out-of-pocket payments become. This would continue to be true even if an annual out-of-pocket maximum limit were to be instituted. For older and disabled individuals who are often on fixed incomes, this can represent an unmanageable burden.

For example, Part D patients purchasing Sprycel® for leukemia in 2018 would have to pay an average of $3,026 in January alone, an amount more than twice the average monthly Social Security benefit. What’s more, approximately 43 percent of the total 12-month out-of-pocket costs for Sprycel® would be due in the first three months of the year. Patients treated with medications for multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis would face similar patterns.

Although the financial resources of Medicare beneficiariesvary greatly, median per capita income is $30,050 among white beneficiaries, $17,350 among black beneficiaries, and $13,650 among Hispanic beneficiaries. Thus, most Medicare beneficiaries likely struggle to afford these high front-loaded out-of-pocket costs, and the current Part D structure is likely to exacerbate health disparities. In addition to the stress this creates, our research examining drug use during specific benefit phases under Part D has found that these high out-of-pocket costs are associated with high rates of treatment interruptions and abandonment of newly prescribed medications at the beginning of the year.

To address this issue of “too much too soon” for patients on long-term specialty drug treatment, we have previously proposed the introduction of both monthly and annual out-of-pocket maximum limits to create more consistent and predictable monthly out-of-pocket costs throughout the year. In short, monthly limits could be set by dividing the annual out-of-pocket maximum by 12. Modeled after the payment options provided by energy companies to protect consumers against huge fluctuations in costs related to seasonal variability in consumption (such as high winter heating bills), this approach would distribute annual costs more evenly across the year and allow individuals to make steady monthly payments. Whereas the logistics of implementing this approach would take some working through, we have demonstrated that such adjustments could be financed via minor increases in Part D premiums (for example, approximately $2 per beneficiary per month).

A Moving Finish Line

Instituting overall protection in the form of an annual out-of-pocket maximum is the most important first step in addressing high out-of-pocket costs for specialty drugs under Medicare Part D. Without it, the impact of “The Good” changes will be diluted, especially by the continued trend toward higher drug prices and the fact that treatment advances are increasingly coming in the form of specialty drugs. Also, while some proposals have identified the catastrophic coverage threshold as the annual out-of-pocket limit amount, little attention has been drawn to the fact that this amount is continuing to increase. Over the past 10 years, the catastrophic coverage limit has risen $950, or 23 percent. This problem is scheduled to worsen over the next couple of years, with a major increase ($1,250) in the catastrophic coverage limit scheduled from 2019 to 2020. This underscores the importance of a more comprehensive approach to Part D reform.

Looking Forward

Solving the problem of high out-of-pocket cost burden will require a multipronged approach. Even sizeable decreases in very high specialty drug list prices are unlikely to lead to major improvements in access without instituting an annual out-of-pocket maximum and paying significant attention to the timing and magnitude of out-of-pocket costs under the current Part D structure. Options are available to redistribute and alleviate current out-of-pocket cost burden without substantially increasing overall costs.