Health Care Access & Coverage

Blog Post

Being Uninsured in America

High costs, hard choices

For the nearly 30 million people in the United States who have no health insurance, gaining access to care and paying for that care can be a challenge. A new “secret shopper” study explores whether the uninsured can get a new primary care appointment, and at what price. To understand what it’s like to be uninsured, a new Bloomberg News project provides the personal stories behind the statistics, highlighting why and how some Americans are going without health insurance.

In Health Affairs, Brendan Saloner and colleagues, including LDI Executive Director Dan Polsky, report findings from a secret shopper study they conducted in 2012/13 and in 2016. In brief, trained auditors called primary care offices in ten states seeking a new patient appointment. The investigators assessed whether appointment availability differed by insurance type and status, both before and after Affordable Care Act (ACA) coverage expansions. This latest study reports the results for callers who said they were uninsured. Would an uninsured caller be offered an appointment, and if so, how much it would it cost? Could the patient make any arrangements to bring less than the full amount to the initial visit (and pay the rest later)? In 2016 the callers also asked about a discount for low-income patients.

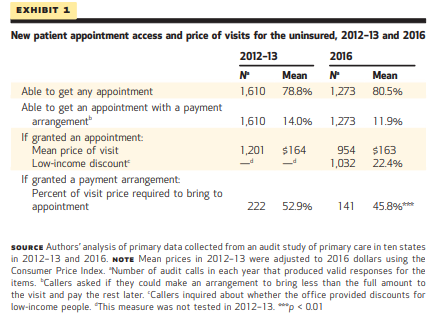

As shown in Exhibit 1, in both time periods, about 80 percent of uninsured callers could get an appointment, at an average cost of about $160. Of those that got appointments, fewer than one in seven could make an alternative payment arrangement, and fewer than one in four (22.4 percent) were offered a low-income discount.

These outcomes differed for different types of primary care practices. In 2016, Federally Qualified Health Centers provided the highest rates of appointment availability (95 percent), at an average price of $89, and were far more likely than other practices to offer a low-income discount (79 percent vs. 19 percent). Practices participating in Medicaid managed care and those with mid-level providers were more likely to offer alternative payment arrangements and low-income discounts.

The average cash price of $160 for a primary care appointment would be unaffordable to many people. In a new Bloomberg News series, journalists John Tozzi and Emma Ockerman provide the human stories that illustrate what the secret shoppers encountered. For example:

Sarah Yoder and her 8-year-old daughter walked out of their pediatrician’s office in early February before the appointment began. Her family dropped their health insurance plan the month before, and the clinic didn’t offer a discount for paying cash. The checkup would have cost $150.

The Bloomberg project is following people who are ‘risking it’ and going without health insurance in the U.S. The series highlights that many individuals are making a choice that the health insurance options available to them, especially with rising deductibles, are too expensive. They’ve had to make tough choices, including insuring some members of the family and not others, and are able to lay out an economic argument for it.

This is consistent with a 2016 Kaiser Family Foundation poll in which 45 percent of uninsured adults said they remained uninsured because the cost of health insurance was too high. And a Commonwealth Fund finding that 85 percent of uninsured adults who shopped for coverage on the individual market, but did not enroll, said it was because they could not find an affordable plan.

The individuals included in the series are somewhat surprising. There’s a middle-age couple from North Carolina with an income that puts them in the top fifth of households, as well as a family of four in Louisiana that are small business owners with an annual income of nearly $150K.

Some are paying cash prices for care, or going without it. Some have chosen to enroll a high-need member of their household while the rest of the family remains uninsured. A few interviewees mentioned enrolling in direct primary care, a form of ‘retainer based medicine’ in which the patient pays a physician directly for services (see more about this and related models here). Others mention seeking out religious health-sharing ministries.

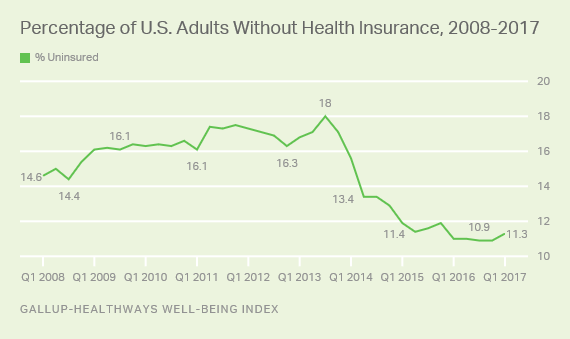

The number of uninsured in the U.S. has been trending upward, after reaching a record low following the ACA’s implementation (see chart). The cost of health insurance clearly contributes to this trend. And for people without insurance, the price of care may often be an insurmountable barrier to care. As we watch the trend line, and debate the reasons for its upturn, we cannot lose track that behind it are real people struggling to afford health coverage and care.