Substance Use Disorder

Blog Post

Better Prescribing for Bad Backs

Patients with Low Back Pain Receiving Fewer Opioids

Low back pain is a major cause of disability among adults and a top reason patients are prescribed opioids. However, a recent study in the Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine finds that patients with new low back pain are receiving opioids less frequently, though prescribing rates remain uneven across the country. Given opioids’ limited effectiveness for low back pain and risk of harm to patients, these results are heartening.

In the study, LDI Associate Fellow Jina Pakpoor and co-first author Micheal Raad found that the percentage of patients who filled opioid prescriptions after visiting primary care for new low back pain declined from 29% in 2011 to 20% in 2016. The authors examined the private insurance claims of over 400,000 individuals who visited primary care with new low back and measured whether these patients had filled an opioid prescription within 30 days of their visit. They excluded patients who had visited a subspecialist for their pain, had an additional spinal diagnosis, or had filled opioid prescriptions in the 90 days prior to their encounter.

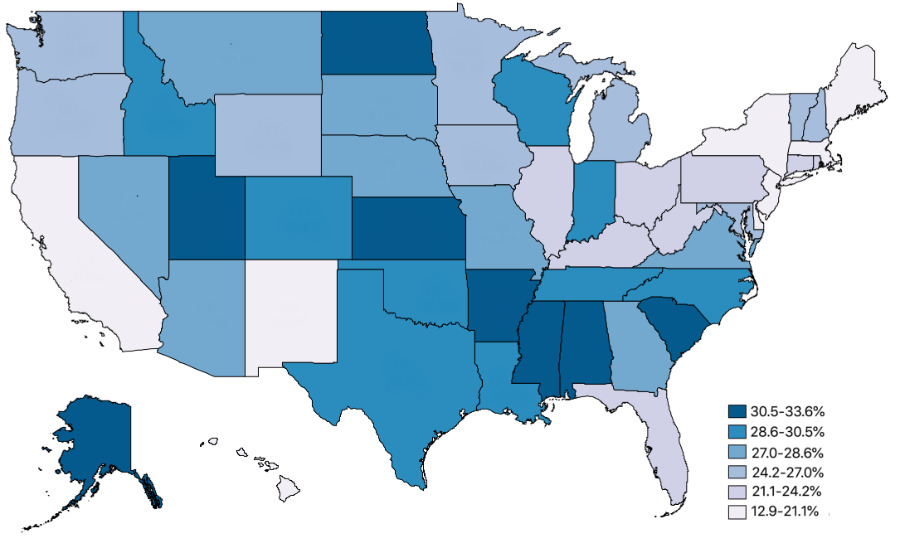

While the percentage of new low back pain patients who received opioids declined overall, prescribing remains substantially different across states. In Hawaii, only 13% of patients had filled prescriptions after their primary care visit, compared to 34% of patients in Arkansas (Figure 1).

These results echo a previous study by Delgado et al. that found significant state variation in opioid prescriptions after an emergency department visit for ankle sprains. Delgado et al. and Pakpoor et al. also identified similar geographic trends. Opioid prescriptions for both low back pain and ankle sprains were concentrated in the South and Midwest, with some states seeing prescribing rates upwards of 30%. However, other states saw stark differences; North Dakota had an opioid prescribing rate of 32% for low back pain, but only 3% for ankle sprains – raising questions around whether local differences in prescribing culture, professional norms, morbidity, or other factors might be influencing these trends.

Pakpoor et al. suggest that the overall decline in opioid prescriptions for new low back pain is likely attributable to greater physician education, statewide prescription drug monitoring programs, and increased awareness around the epidemic. However, the continued high rates of prescribing in some states is alarming. It is important to consider what might be driving state variation in prescriptions, and to ensure that new evidence-based guidelines and local health policies reflect these differences. Prescribing practices also must take into account individual patient needs and circumstances.

This study indicates that progress towards reducing inappropriate opioid prescribing for low back pain in primary care has been steady, but far from uniform. Ultimately, Pakpoor et al. suggest that reducing inappropriate opioid prescriptions for low back pain will demand a multifaceted and collaborative approach across patients, physicians, and payers. Although national guidelines advise against using opioids for low back pain until other treatments have been tried, insurance coverage for other therapies is often scarce or restricted. Reductions in prescribing must be paired with further research into more effective treatments for low back pain, as well as better coverage of non-opioid alternatives.

The January 2020 JABFM article, Variability in Opioid Prescribing Practices for New Low Back Pain in the Primary Care Setting, was authored by Micheal Raad, Jina Pakpoor, Andrew Harris, Varun Puvanesarajah, Majd Marrache, Joseph K. Canner, and Amit Jain.