Blog Post

The Case For Using Novel Value Elements When Assessing COVID-19 Vaccines And Therapeutics

[Original post: Sachin Kamal-Bahl, Richard Willke, Justin T. Puckett, and Jalpa A. Doshi, The Case For Using Novel Value Elements When Assessing COVID-19 Vaccines And Therapeutics, Health Affairs Blog, June 23, 2020. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200616.451000/full/. Copyright ©2020 Health Affairs by Project HOPE – The People-to-People Health Foundation, Inc.]

In the span of mere weeks, the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) has upended modern life. Schools and businesses across the country have been shuttered, and the global economy faces the worst downturn since the Great Depression. While the pandemic itself is unprecedented, the situation is particularly alarming given the absence of virtually any therapeutics or vaccines that can treat or prevent COVID-19. Pharmaceutical companies large and small have rapidly expanded research efforts over the past weeks, and there are now more than 70 COVID-19 drug and vaccine trials registered with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

While a transformative therapeutic is several months away (and a vaccine will likely take at least a year or longer), discussions and debates on the potential value and appropriate price of these treatments are already taking place. These conversations became far less theoretical last month with the FDA’s issuance of an emergency use authorization for remdesivir to treat hospitalized COVID-19 patients. The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) immediately released results of two analyses that offer a lower and upper bound for an appropriate price for remdesivir. The cost-recovery approach that ICER used to determine a lower bound has been widely criticized, particularly with respect to the negative impact such a pricing scheme would have on innovation. ICER’s proposed upper-bound price, developed using a traditional cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) approach commonly used to capture value of a treatment, has received a more mixed response and is worthy of further exploration.

The Limitations Of Traditional Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

Traditional CEA is regularly used by organizations such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK to determine the value and appropriate price for new treatments. ICER also uses traditional CEA for all its value assessments. Traditional CEA focuses on incremental costs and incremental benefits generated by a new treatment relative to available alternatives. Incremental benefits offered by the treatment are typically measured using quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), a generic measure combining how well a treatment extends life or improves quality of life. However, QALYs are an imperfect metric and capture only a subset of the benefits that may be produced by a treatment. Traditional CEA based on QALYs often neglects additional benefits that accrue to patients or society at large and does not always provide a comprehensive view of the value of a treatment.

So what elements of value are not incorporated in traditional CEA? A 2017 paper by Louis Garrison, Sachin Kamal-Bahl, and Adrian Towse identified and discussed five novel elements of value that are traditionally not incorporated in CEA, but which may be relevant to fully quantifying the value of a treatment. These novel value elements were expanded upon in a report from the International Society of Pharmacoeconomic and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) Special Task Force on Value Assessment Frameworks.

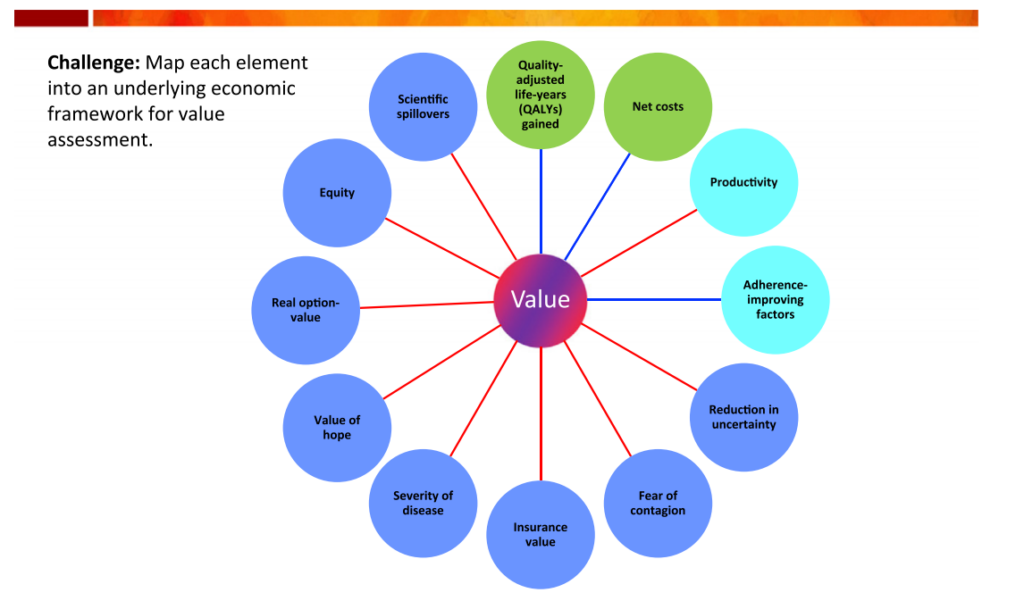

Exhibit 1 is the so-called “value flower” from the ISPOR Special Task Force Report, wherein the novel elements of value are displayed in dark blue circles. Traditionally incorporated value elements and occasionally considered value elements are shown in green and light blue circles, respectively. While the ISPOR Special Task Force discussed these novel elements of value in broad strokes, many of these elements have particular significance in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and are discussed below.

Exhibit 1: Elements of value

Fear Of Contagion

By limiting the spread of disease, an infectious disease vaccine or treatment is beneficial to both untreated patients and society at large. In the context of infectious disease, traditional CEAs often include benefits that extend beyond the treated patients, but they do not normally include the benefits of reducing the fear of contagion. There has been widespread media coverage of severe COVID-19 cases, and thus the public is acutely aware of the threat that disease severity poses. A potential COVID-19 vaccine or therapeutic could significantly reduce the anxiety associated with the risk of contracting the disease or of hospitalization and death among all individuals, not just those who are exposed or sick. Hence, the value of reducing the fear of contagion should not be underestimated. In addition, fear of contagion is one of the key drivers behind stay-at-home orders, social distancing practices, and limits on social engagement. The ensuing economic losses—measured in trillions of dollars in the US alone—may have been averted by the ready existence of effective COVID-19 treatments. A future COVID-19 vaccine could alleviate concerns about disease spread, which have fueled the global economic slowdown. A proper value assessment should factor in these possible benefits when assessing potential treatments.

Insurance Value and Reduction in Uncertainty

New options to treat or prevent COVID-19 also reduce both physical and financial risks in the ongoing pandemic. The willingness to pay for coverage of such options constitutes the insurance value of a given treatment, which is based on most people being risk-averse. Traditional CEA has historically ignored the role of risk and uncertainty in mediating the value of new treatments by focusing on only measuring the benefits accruing among patients with the illness. To individuals not yet infected by the coronavirus, COVID-19 represents a risk rather than a certainty. New COVID-19 vaccines or therapeutics will reduce their physical risk of getting sick or experiencing severe complications; availability of such treatment options will also make insurance coverage more useful by reducing the financial risk. Most people would likely be willing to pay for insurance coverage of treatments for COVID-19 to reduce their physical and financial risks in this pandemic. A related element is the psychological benefit that comes through the concept of “reduction in uncertainty,” sometimes called the “value of knowing” that an effective treatment or vaccine for COVID-19 could significantly reduce the probability of a bad outcome. Methods to quantify such value elements have been developed and should be accounted for in value determinations of COVID-19 therapeutics and vaccines.

Severity of Disease

The value of a treatment can also be impacted by the severity of an illness. For a given size health gain (as measured by QALYs), there is greater willingness to pay the greater the severity of the disease. This may be due either to the patient’s own valuation or to the priority that society places on relieving extreme suffering. Consider the more severe cases of COVID-19, which have required hospitalization and have involved cytokine storms and often the use of a ventilator to assist in breathing. The potential for severe disease outcomes exacerbates the fear of contagion and elevates concerns about normal levels of social engagement. The COVID-19 situation is a dramatic illustration of the importance of those two value elements.

Value of Hope

The concept of the value of hope is based on our tendency to focus on the potential for the optimal outcome, rather than focusing on the average outcome—such as the reason for buying a lottery ticket. It has been applied mainly in cases such as cancer immunotherapies that completely cure a subset of patients, even though median or mean survival across all patients may not be greatly improved. In the case of COVID-19, patients who must be put on a ventilator have a high risk of mortality, and even those who survive may have continuing respiratory problems. A treatment that would increase the likelihood of long-term survival without any problems in some patients—even if the average patient still has a bad outcome—would likely be more highly valued by patients than the average QALY gain would suggest. There has been significant work on quantifying the value of hope in the context of CEA. Stakeholders should apply this knowledge to their assessments of new COVID-19 treatments.

Real Option Value

Although numerous clinical trials are ongoing for COVID-19 therapeutics and vaccines, it is not clear whether, or when, significant future advances will occur. Thus, a treatment that extends life can provide patients with an option to enjoy these uncertain future benefits: This is the real option value generated by the treatment. Consider again the use of a drug such as remdesivir in treating COVID-19. If it does not cure a given patient, it may still be valuable in the sense that it may extend the patient’s survival long enough for other treatments just coming on line or in short supply to be used to help the patient. While prior empirical research has shown real option value to have a large impact on the valuation of oncology treatments, it may be worth exploring this value element in the context of COVID-19.

Scientific Spillovers

The value of a treatment is also related to its potential for scientific spillovers, whereby the work done on an existing treatment, such as remdesivir, informs subsequent research and innovation on other COVID-19 therapeutics. For instance, in response to data from a remdesivir trial, Anthony Fauci, MD, suggested that the findings were important because they represent “proof of concept…that a drug can block this virus.” Other researchers and manufacturers can build upon the knowledge that a particular approach works to combat the coronavirus and may offer a path to even more transformative COVID-19 therapeutics and vaccines in the future. In fact, it is likely that early innovators may not benefit as much from their scientific discoveries as other companies able to build upon these discoveries and develop more successful treatments later. Hence, scientific spillovers occur “when the benefit of scientific advances cannot be entirely appropriated by those making them.” To account for this, some value assessment frameworks have an allowance for the scientific novelty of a therapy, but traditional CEA does not incorporate this value element. Quantifying and operationalizing scientific spillover effects is difficult, but the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of this component of value.

Equity

The value element of equity is based on placing greater priority on treatments that reduce health inequities. Given that certain underserved minorities, mainly African Americans, are being infected and dying disproportionately with COVID-19, effective treatments for COVID-19 could reduce such inequities. Several approaches have been proposed for incorporating equity into health technology assessments and should be considered in the context of valuing COVID-19 therapeutics and vaccines.

Additional Value Elements: Family Spillover Effects

The traditional approach to CEA relies almost exclusively on the value of improved health to patients and does not account for the value of improvements to the lives of family members and loved ones. It fails to recognize that “life is valuable not just to those whose life is at stake but also to loved ones.” Family spillover effects are particularly relevant in the context of COVID-19, wherein family members are not even permitted to visit their sick loved ones in the hospital given how contagious it is. The disutility to the family members and friends is enormous, and prior research has shown that incorporation of such family effects in CEA may better reflect the value of treatments.

Conclusion

To incentivize product innovation at a level that recognizes its full value to patients and society, there is a clear need to move beyond the traditional cost per QALY approach and consider novel elements of value in the context of COVID-19. As scientists continue their efforts to develop new therapeutics and vaccines to treat and prevent COVID-19, other stakeholders—health technology assessment bodies, payers, policy makers, manufacturers, and health economists—have a responsibility to also ensure innovation in value assessment. The recent ICER analysis of remdesivir failed in this respect by not adequately addressing novel elements of value (even as contextual considerations) that are of particular relevance in the ongoing pandemic. While contentious debates surrounding the value and price of new therapies are likely to continue, the COVID-19 saga should make clear the importance of rethinking the existing paradigm and avoiding business as usual.