Health Care Access & Coverage

Blog Post

Fast-tracking Behavioral Health Care

Replacing red tape with integrated care (part 1 of 2)

Imagine struggling with a behavioral health issue, searching for a local psychiatrist, and finding out the provider you’ve chosen doesn’t accept insurance. You wouldn’t be alone: most psychiatrists in the United States don’t. But let’s say your plan has some out-of-network benefits, which means you pay the full cost up front and request an itemized receipt for every appointment. If you put together your receipts, fill out a lengthy form, and send them to your insurer, you could get a fraction of your money returned to you in a couple of months…. as long as you’ve met your deductible, and your paperwork is completed and processed correctly.

Deciding to get help from a behavioral health professional in the United States is a major step, especially when you or a family member are already struggling with the symptoms of a serious mental illness or substance use disorder. Unfortunately, this obstacle course may be your best-case scenario when you do. Many health plans don’t have out-of-network benefits for behavioral health, and many individuals don’t have the savings to front hundreds of dollars while waiting for reimbursement. Moreover, hundreds of thousands of Americans with behavioral conditions experience homelessness or are incarcerated each year, further complicating access to high-quality care. And acknowledging and seeking treatment for behavioral health conditions is still stigmatized in the United States for people from all walks of life.

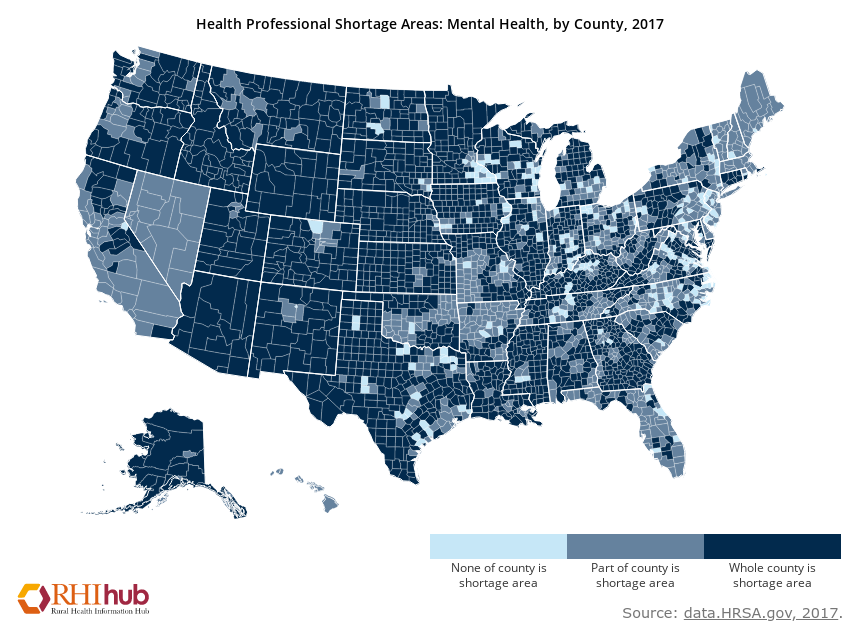

The key driver of inadequate access is that the demand for behavioral health care far exceeds the supply of clinicians specializing in this area. By some estimates, nearly half of us will experience a behavioral health condition—a catchall term for psychiatric disorders and conditions like substance use disorder—in our lifetime. Yet the Health Resources and Services Administration reports an ongoing shortage of psychiatrists and projects shortages of clinical, counseling, and school psychologists, mental health and substance abuse social workers, school counselors, and marriage and family therapists by 2025. Lack of access to these providers is particularly acute for male, African-American, lower-income and rural patients, who struggle more often than their counterparts to find a therapist.

But what if patients could access behavioral health care through a regular visit to a primary care office or during a hospital stay? This is the premise of integrated care, a promising strategy for addressing shortcomings in the traditional model of behavioral health care provision. Though the concept of integrated care isn’t new, changes in reimbursement are hastening its implementation. While integrated care can address many supply-side issues, it may also encourage demand, as patients have reported a preference to receive behavioral health care in a non-psychiatric setting.

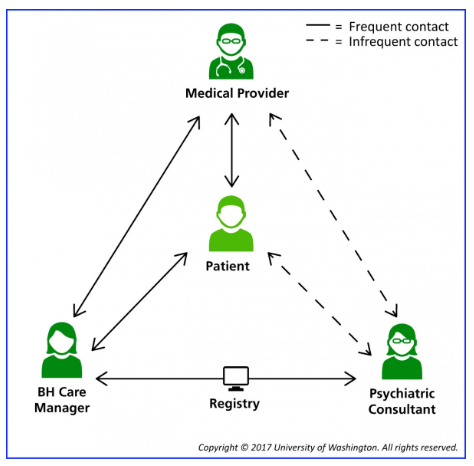

A gold standard of integrated is the evidence-based collaborative care model. In this model, a non-psychiatrist — typically a primary care physician or nurse practitioner — delivers behavioral health care directly to patients in consultation with a psychiatric expert (either a psychiatrist or, when permissible, a psychiatric nurse practitioner) and behavioral health manager.

Collaborative care encompasses screening and assessment, medication management, and case management, and emphasizes coordination of care for physical and behavioral health conditions, which are often intertwined. Studies have demonstrated that collaborative care can benefit adults with depression and anxiety disorders, adolescents with depression, and children with behavioral problems, ADHD and anxiety. And while collaborative care is not feasible for all practices, the concept of integrated care is flexible enough to adapt to many modes of care delivery.

Models of integrated care can also address the opioid epidemic by increasing timely access to evidence-based treatments for patients with opioid use disorder. For example, expertise from psychiatric consultants and behavioral health managers can guide primary care providers through the maze of medication therapy and psychosocial services in a collaborative care model. This support is critical for increasing access to buprenorphine in particular, which currently requires a waiver from the Drug Enforcement Agency. (An ongoing movement to eliminate waivers for buprenorphine would make substance use treatment even more accessible in primary care settings.)

Of course, many Americans reside in areas with a severe shortage of not only behavioral health providers, but also primary care providers. Tools like mobile units and telepsychiatry can be leveraged to address these shortages when integrating care. Moreover, expanding scope of practice for psychiatric nurse practitioners, licensed clinical social workers, and psychologists could support the implementation of integrated care in underserved areas. In these scenarios, psychiatric experts and pharmacists can serve as ongoing resources to increase the use of best prescribing practices among non-psychiatrists providing behavioral health care.

As evidence of its efficacy grows, payers have begun showing support for integrated care. In 2017, Medicare led the way by introducing a set of payment codes that directly reimburse behavioral health care delivered by non-psychiatrists and incentivize collaborative care with higher payments. These payment codes are flexible enough to reimburse services provided in the offices of primary care providers and non-psychiatric specialists, as well as remotely via telehealth. State Medicaid programs and some self-insured employers have begun adopting similar reimbursement codes as well. However, the introduction of new reimbursement codes has not been without its growing pains. Some providers and payers have expressed confusion about what kind of care is covered.

Because behavioral health care has been historically siloed from physical health care in terms of both delivery and reimbursement, the fixed costs associated with integrated care –and particularly collaborative care –may pose more challenges than making changes to behavioral health care delivery alone. Integrated care approaches will only sustain themselves if they prove to be a clinically effective and cost-effective model. One important consideration is triage to primary versus specialty care, which entails practices optimizing the use of personnel to increase efficiency.

In our next blog post, we’ll highlight a number of ongoing initiatives at health systems, including Penn Medicine, that use interdisciplinary, team-based approaches to integrate behavioral health care in hospital acute care wards, primary care clinics, emergency rooms and beyond. As these models of integrated care are adapted to new settings, the hope is that fewer patients will face an obstacle course in order to receive the behavioral health care they need.