Improving Care for Older Adults

Blog Post

Medicare SNF Payment Policy: What a Difference a Day Makes

Length of stay linked to readmissions

It is hardly surprising that there’s a spike in the number of Medicare patients discharged from postacute care in a skilled nursing facility (SNF) the day before their copayment jumps from $0 to more than $150. However, the question remains whether this payment policy – which completely covers the first 20 days of a SNF stay – affects patient outcomes in any way. If it induces longer-than-needed stays up to the payment “cliff,” patients are not likely to suffer, though the Medicare budget might. If it induces shorter-than-needed stays (even by a day), patients may be harmed.

A recent study by Rachel Werner, Norma Coe, and colleagues now gives us some answers, and heightens concerns that Medicare’s SNF payment policy is having negative, unintended effects on patient outcomes, measured by readmissions to hospitals.

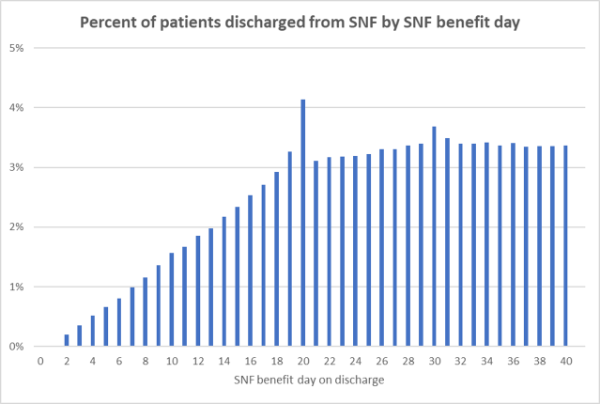

Earlier research found that Medicare patients were more likely to be discharged from a SNF if they were nearing the 20th day in their “SNF benefit period.” That benefit period begins on the day of admission to a SNF, can last up to 100 days, and can span multiple SNF stays. Under the current policy, Medicare pays for the first 20 days of a patient’s SNF benefit period; on benefit day 21, patient copays increase from $0 to over $150 per day. Reflecting this spike in copays, patient discharges increase by 60 percent between days 19 and 20.

In the recent study, Werner and colleagues identified a cohort of about 300,000 Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries who went to a SNF after hospital discharge between 2012 and 2016. These beneficiaries had a recent, prior SNF stay, so had already used part of their SNF benefit period. The authors leveraged day-21 discharge patterns to examine the impact of the SNF payment policy on patients’ SNF length of stay and outcomes after discharge. They found:

- SNF benefit day on admission predicts SNF length of stay. Patients who had used more SNF benefit days upon admission had shorter stays: having used one additional benefit-day at the time of SNF admission was associated with a 0.3-day shorter stay.

- Patients with longer SNF stays were less likely to be readmitted to a hospital within 30 or 90 days of hospital discharge. Focusing on patients discharged on day 20 versus day 21, one additional day in a SNF was associated with a 1.5 and 1.1 percentage point-reduction in hospital readmissions within 30 and 90 days of hospital discharge, respectively.

- Shorter SNF stays led to only partial savings for Medicare. In the 90 days after SNF discharge, spending one less day in a SNF cost Medicare $179. This higher spending after SNF discharge was driven by higher rates of hospital readmissions. However, one less day in a SNF also saved Medicare $591, offsetting those higher costs from hospital readmissions and leading to partial savings.

This study demonstrates that Medicare’s SNF payment policy is associated with shorter SNF stays and higher hospital readmission rates. Although value-based care efforts focus on reducing unnecessary spending and utilization, in the case of SNF payment, the pendulum may have swung too far in the other direction. These results suggest that the copayment policy prompts early discharges that are less-than-optimal for patients’ health, while generating only modest savings to Medicare. Further, given that patients discharged earlier in their benefit period are more likely to be racial and ethnic minorities living in high poverty areas, the policy also could worsen health disparities.

Policymakers looking to cut health care spending must consider the potential unintended and negative consequences of payment policies for patients. A better approach than an arbitrary copayment cliff is sorely needed. You can read the full study here.