Substance Use Disorder

Blog Post

Responding to the Opioid Epidemic: There’s an App for That

Real-time tracking of opioid overdoses

Earlier this year, Pennsylvania Governor Wolf declared the opioid epidemic a disaster emergency. Pennsylvania has the fourth highest rate of overdose deaths in the country, and its rural counties experienced a 42% increase in drug overdose deaths from 2015 to 2016. But to successfully treat the epidemic as a disaster, the Commonwealth needs timely overdose data. An effective disaster response requires up-to-date information, to allocate resources efficiently and promote recovery. A new app may provide a way to track overdoses in real-time.

With only 10 health departments for all 67 Pennsylvania counties, it is challenging for county officials to provide accurate and timely overdose data. Investments in data systems–including the federal Enhanced State Opioid Overdose Surveillance grant–have improved reporting times from Emergency Departments and first responders, but a lag remains.

Pennsylvania emergency medical services (EMS) agencies must report all patient care, including overdoses using an approved electronic patient care report (ePCR) data system. These data are then transferred to CloudPCR, which serves as the Commonwealth’s data bridge system. According to an official at the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Bureau of Emergency Services, statewide reports specific to overdoses in which naloxone is used are generated and shared weekly with the Opioid Operations Command Center. This means overdose data may not be viewed at the command center until a week or more after the incident.

Moreover, there is no state mandate to report nonfatal overdoses, unless naloxone provided through the Pennsylvania Naloxone for First Responders program was administered. Nonfatal overdoses are a risk factor for fatal overdoses, and an essential measure for the evaluation of key public health programs and for determining the resources required to meet a community’s need.

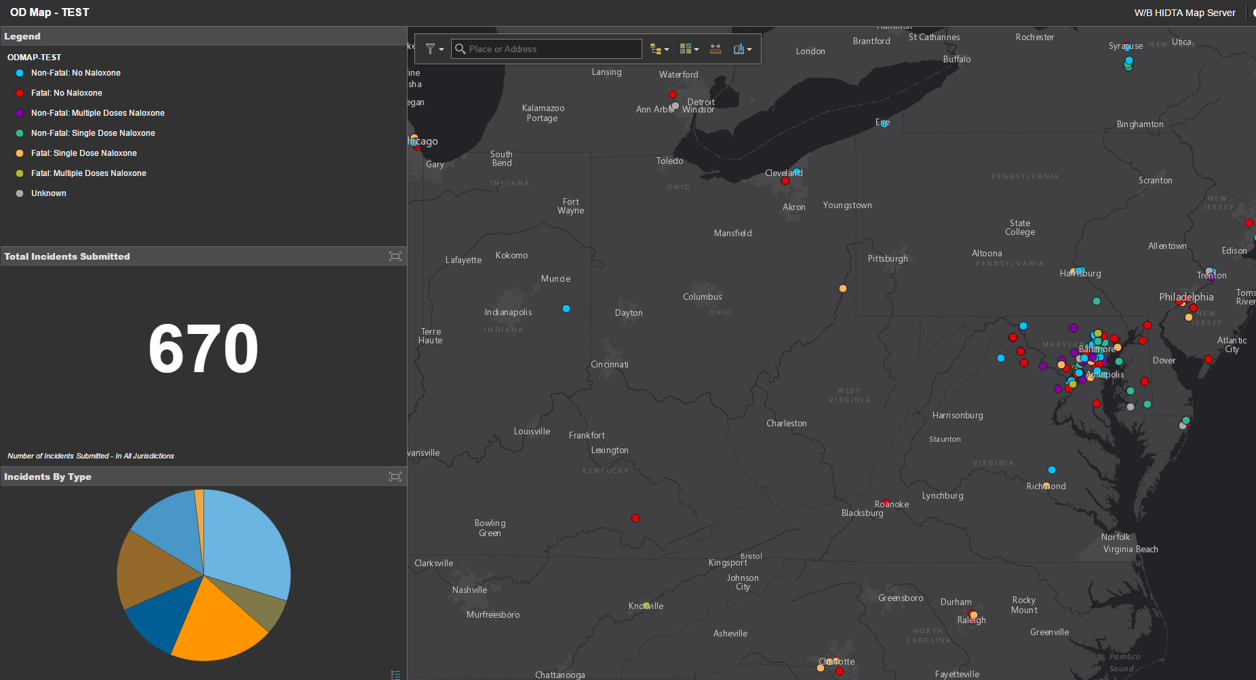

Other states and localities have improved the timeliness of data on opioid both fatal and nonfatal overdoses though adoption of real-time reporting systems such as the Overdose Detection Mapping Application Program (ODMAP), a free program developed by the Washington/Baltimore High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas (HIDTA). Launched as a pilot in January 2017, it is now used by more than 900 agencies across 40 states. In the first year after its national launch, first responders logged more than 18,000 overdoses on the map. The system allows first responders to log overdose data through an interface that can accessed through any mobile device. ODMAP collects, date, time, location, as well as naloxone administration (number of doses given) and the status of the patient (fatal/nonfatal) at the scene of an overdose. Florida and Maryland recently passed legislation mandating the use of ODMAP and effective July 1, Maryland is submitting all overdose data to the system.

The application has several capabilities that make it especially useful to public health and law enforcement officials. It provides “spike alerts” to identify overdose outbreaks. This allows public health officials to immediately dispatch additional units or a rapid response team, essential to curb the rise in potent synthetic opioid (such as fentanyl) deaths. Overdose deaths with fentanyl occur more rapidly and may require additional medical intervention than heroin alone.

Real-time tracking also offers opportunities to identify trends using geolocation, as shown below. This interface is available to public health and safety officials with log-in credentials. With this information, public health officials can design interventions to target high-risk populations, while law enforcement agencies can identify drug routes.

Real-time reporting apps can also be continuously updated to improve software capabilities. Jeff Beeson, Deputy Director at Washington/Baltimore HIDTA, said that ODMAP will be used by law enforcement in New Jersey to document naloxone administrations statewide, reducing the reporting burden on local agencies. Beeson noted that statewide movements to use the platform would give leverage to those states and their priorities as HIDTA continues to expand system capabilities. This could include new features, such as naloxone inventory, which would improve the Commonwealth’s ability to track and manage its naloxone supply. This would ensure counties have doses on hand before reaching dangerously low levels.

Finally, the platform can serve as the state’s standardized reporting system. County agencies utilize various methods of reporting, including fax in some instances. A standard platform across the state will reduce the current lag time, providing the Opioid Operations Command Center real-time overdose information, and increase data sharing across jurisdictions, to better coordinate responses to the epidemic.

There is anecdotal evidence of ODMAP’s law enforcement and public health success. In Anne Arundel County, Maryland law enforcement officials credit ODMAP for linking overdoses to a drug-trafficking organization, which helped lead to its ultimate dismantling. In contrast, ODMAP was used to connect peer recovery specialists with individuals who overdosed in Erie County, New York to discuss treatment options. Of the first 35 individuals referred to the peer support program, 19 agreed to enter substance use disorder treatment within the first 60 days.

Despite the rapid early adoption, rigorous process and outcome evaluations are warranted to overcome barriers to use and to assess the platform’s effectiveness in improving responses to the opioid epidemic. With increased adoption across jurisdictions and more complete datasets to work with, researchers will be able to more fully evaluate the process and outcomes of this innovative program. Ultimately, however, it is the local first responder buy-in that will be critical to successful implementation.