Health Equity

Blog Post

Responding to the Trauma of COVID-19

Individual and Community Actions

As the country looks to reopen and epidemiologists anticipate future waves of coronavirus (COVID-19) cases, we must address an equally important “pandemic:” the virus’ far-reaching mental health and trauma-related consequences. Whether balancing activities of essential work with exposure risk, bearing witness to suffering or loss, or feeling anguish or guilt for not “doing more” during this time, our society is facing great adversity with potentially devastating consequences.

Moreover, the trauma of COVID-19 does not stand alone. It layers on top of the trauma and grief of watching the death of George Floyd and remembering Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and many others. It layers on top of the intergenerational trauma of racism rooted in slavery, mass incarceration, police brutality, and Black oppression.

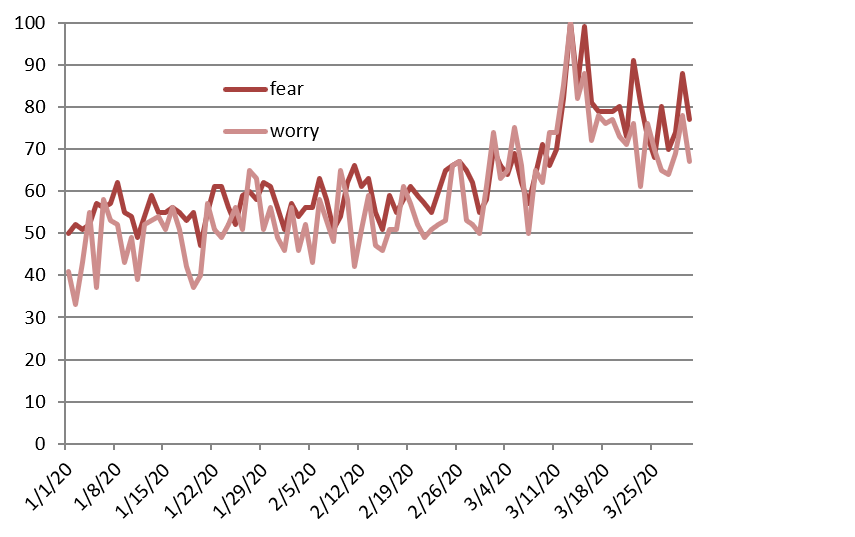

Trends in online data reveal a mounting wave of trauma as a result of COVID-19. Google searches for terms like “fear” and “worry” surged beginning in March (Figure 1). This foreshadowed the recent Census Bureau data showing almost a third of Americans are suffering from clinical symptoms of depression or generalized anxiety, currently doubling from the prior national survey in 2014.

Evidence-based frameworks exist to guide our individual and collective response and prevent the pandemic’s trauma-related effects. While racial trauma is currently being exposed alongside the trauma of COVID-19, it is important to distinguish that while these traumas may result in similar symptoms, they are not the same, nor are their solutions. What does a trauma-informed framework tell us about how to respond to this mounting crisis to mitigate the aftershocks from the pandemic?

Trauma-Related Effects During COVID-19 and Other National Emergencies

According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), trauma consists of: 1) an event, like illness and disruption related to COVID-19; 2) the experience of the event, such as feeling sick, grieving loss, or fearing death; and 3) the ultimate effect, which may range from mild anxiety to severe symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This can predispose people to serious acute and chronic health conditions, as observed with other national emergencies and tragedies. For example, prior work has demonstrated that isolation alone can increase the risk of suicidality and chronic health conditions like cardiovascular disease. Additionally, longitudinal follow-up after September 11th, 2001 demonstrated that the post-traumatic stress of large-scale devastation can increase cardiovascular risk and all-cause mortality in both responders and civilians.In the case of COVID-19, children may suffer mental health and lifelong physical health consequences associated with adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), such as separation from caregivers on the front lines, or exposure to violence in our society or within their own homes due to shelter-in-place policies.

Applying the SAMHSA Framework for Disaster Response

SAMHSA’s trauma-informed approach to disaster response—realize, recognize, respond, and resist re-traumatization—offers a framework for mitigating the aftershocks of the pandemic.

1. Realize our collective, yet different, experiences of trauma

Though no individual’s situation is the same, the COVID-19 pandemic has created a shared human experience of remarkable uncertainty, isolation, and hardship. Thus, realizing and acknowledging trauma within our own lives and the lives of others is an important first step to mitigate its impact. Previous research has outlined the diverse manifestations of psychological distress during national emergencies, mostly stemming from uncertainty and fear. Even empathizing with vivid images on the news while sheltering in place could lead to increased anxiety and stress with negative long-term health consequences. However, the COVID-19 pandemic adds a layer of isolation and hardship due to our need to cope with this reality collectively while remaining physically distanced.

The risk of experiencing trauma is heightened for certain groups, including frontline clinicians, ill patients, and the families who have lost loved ones. Other vulnerable groups include those at high risk for serious complications of the virus, as well as individuals with limited access to information and care because of socio-structural disparities. For these groups in particular, we need to apply “psychological first aid,” or mental health support to reduce distress and foster adaptive functioning long-term. For example, some hospitals have made multidisciplinary mental health teams immediately available to frontline providers, while New York State is waiving mental health costs. Rehabilitation for recovering COVID patients has begun to include screening for mental health impacts such as “post-intensive care syndrome.” Moving forward, health systems should use “disaster psychiatry” frameworks to implement standardized assessments of primary and secondary trauma responses along with targeted interventions.

2. Recognize the signs, symptoms, and impacts of trauma

Trauma can manipulate our neurobiology, manifesting in physical symptoms such as poor gastrointestinal function, loss of energy, or pain, and mental symptoms such as poor memory and concentration, mood swings, and feelings of guilt. Such symptoms were prevalent in up to 7% of the population in China just one month into the coronavirus crisis. Recently, American clinicians have highlighted how COVID-19 stress can manifest in many different forms in the body. In youth, physical symptoms such as aches or pains and behavioral symptoms such as withdrawal, regression, and agitation can indicate trauma. Unaddressed symptoms in children can also lead to misdiagnosed behavioral health problems, increasing the risk of mental illness, cancer, heart disease, and mortality later in life. Persistent trauma that is not buffered by early intervention and social support can permanently alter our DNA and promote vulnerability to future stressors. As evidenced by Holocaust survivors, psychological wounds can be transmitted to future generations.

3. Respond individually and at the community level

Individuals can take steps to disrupt negative responses to trauma. The CDC and the American Psychological Association recommend actions such as preparing meals with whole fresh foods, mindful breathing, and grounding exercises. Families can have open discussions with children about the pandemic, follow regular routines, and prioritize wellness activities and bonding time. People with existing mental health or substance use disorders can find virtual help through SAMHSA, and for families, the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Communities can respond by enacting equitable policies to help those most vulnerable to trauma and by treating neighbors with empathy and kindness, given evidence that compassion fosters resilience. Acts of compassion can involve delivering groceries or masks to those more vulnerable, posting motivational signs in windows for essential employees, or disseminating mental health resources and hotline numbers to reach those suffering in silence. We can advocate for community needs by attending virtual town halls and contacting local policymakers. The Campaign for Trauma-Informed Policy and Practice recommends policies that prevent and respond to childhood trauma and build resilience.

4. Resist re-traumatization by addressing disparities that will leave some individuals or communities to suffer

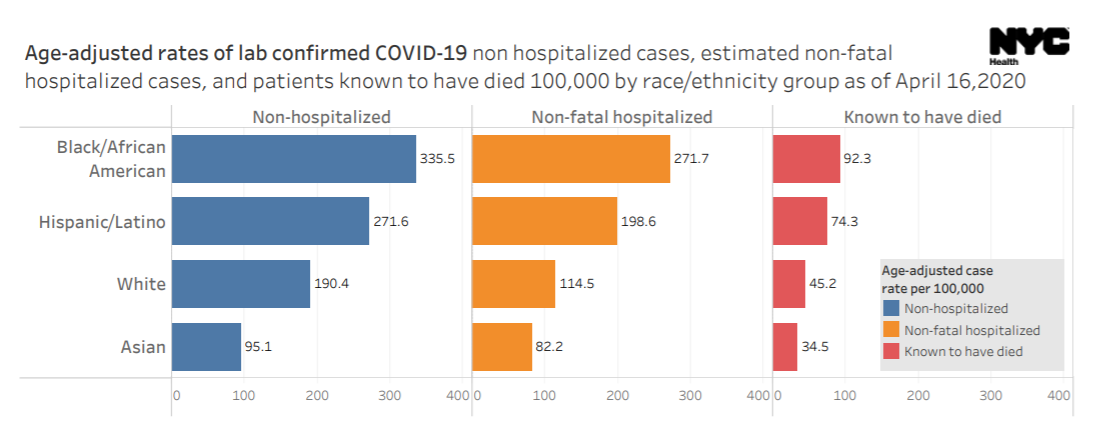

Like past epidemics, including cholera, tuberculosis, syphilis, and HIV, COVID-19 has created complex trauma and added a layer to pre-existing hardship, driving further disparities. Such disparities have likely paved the way for larger numbers of deaths in black communities who already experience high rates of economic hardship, morbidity, and premature mortality. Black Americans are experiencing double the death rate of White Americans from COVID, yet historically half the number of Black Americans compared to White Americans receive mental health services nationally (Figure 2).

Similar disparities may be expected for those who live in detention, homeless shelters, or around violence. Some members of other groups may be experiencing complex trauma at this time, such as those struggling to seek care for COVID symptoms with limited English proficiency, fearing for their lives in incarceration, or facing anti-Asian discrimination. Current events may aggravate past wounds for individuals who have experienced trauma in other areas of their life, requiring additional support measures. Avoiding retraumatization through the recognition of structural racism, action to provide inclusive and transparent COVID-19 testing, and distribution of equitable health care and financial resources is essential as we make a conscious effort to minimize unintended consequences for particularly vulnerable groups.

Federal and State Policymakers Need to Take Action

At the federal level, an inter-agency task force should be created among SAMHSA, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the National Institute of Mental Health. This task force should look beyond public education and research and create pandemic trauma responsiveness guidelines for states. The federal government should back up these recommendations with dollars to implement trauma-informed policies. Policymakers do not need to start from scratch. There are effective models to mitigate trauma and distress at the state, federal, and global level. For instance, New Hampshire has developed violence, substance use, and family resiliency support networks; the national CARES Act aims to support citizens in financial distress; and France has facilitated community partnerships to allow pharmacies to serve as social service emergency rooms.

To respond to the diverse needs of our communities, the country needs to build on these examples and embrace other innovative ideas. This could include: 1) states creating a centralized social resource center that can provide, track, and quantify changing community needs as a result of COVID-19; 2) health care delivery systems using prompts to promote provider screening of COVID-19-related concerns of home safety and stress exposure; or 3) the federal government sending stimulus funds for employers to provide mental health services. All policies and programs must be created with a conscious effort to aid communities equitably, and incorporate anti-racism and culturally responsive actions.

Community Healing and Resilience

In the aftermath of COVID-19’s trauma-related effects, harnessing a spectrum of resilience from individual and community-level acts – to paradigm and policy shifts that fight the inequities of complex trauma – will lay the building blocks for collective healing. By addressing the trauma that surrounds the pandemic now, we can create fertile ground for trauma-informed healing and recovery in our communities, well beyond when COVID-19 cases subside.

Robin Ortiz, MD, and Laura Sinko, PhD, RN, CCTS-I are Penn LDI Associate Fellows, National Clinician Scholars, and candidates in the Master of Science in Health Policy Research program.