Health Care Access & Coverage

Blog Post

Tracking a Trend: Nursing Home Specialists

Early evidence on outcomes, costs

The world of health care is divided into many areas of specialization. At one point or another, we may have seen a podiatrist for a foot problem or a dermatologist for skin issues. Not all of us realize that – in addition to specializing in, say, the lungs – clinicians can devote their practice to providing general care to patients in a specific setting. For example, some physicians, called ‘hospitalists,’ see all or most of their patients in a hospital environment. A more recent illustration of this concept is nursing homes specialists, or ‘SNFists,’ who focus on caring for patients in nursing homes (skilled nursing facilities). Nursing homes deliver short-term post-acute care to patients after discharge from the hospital, as well as long-term care to patients with more extensive needs.

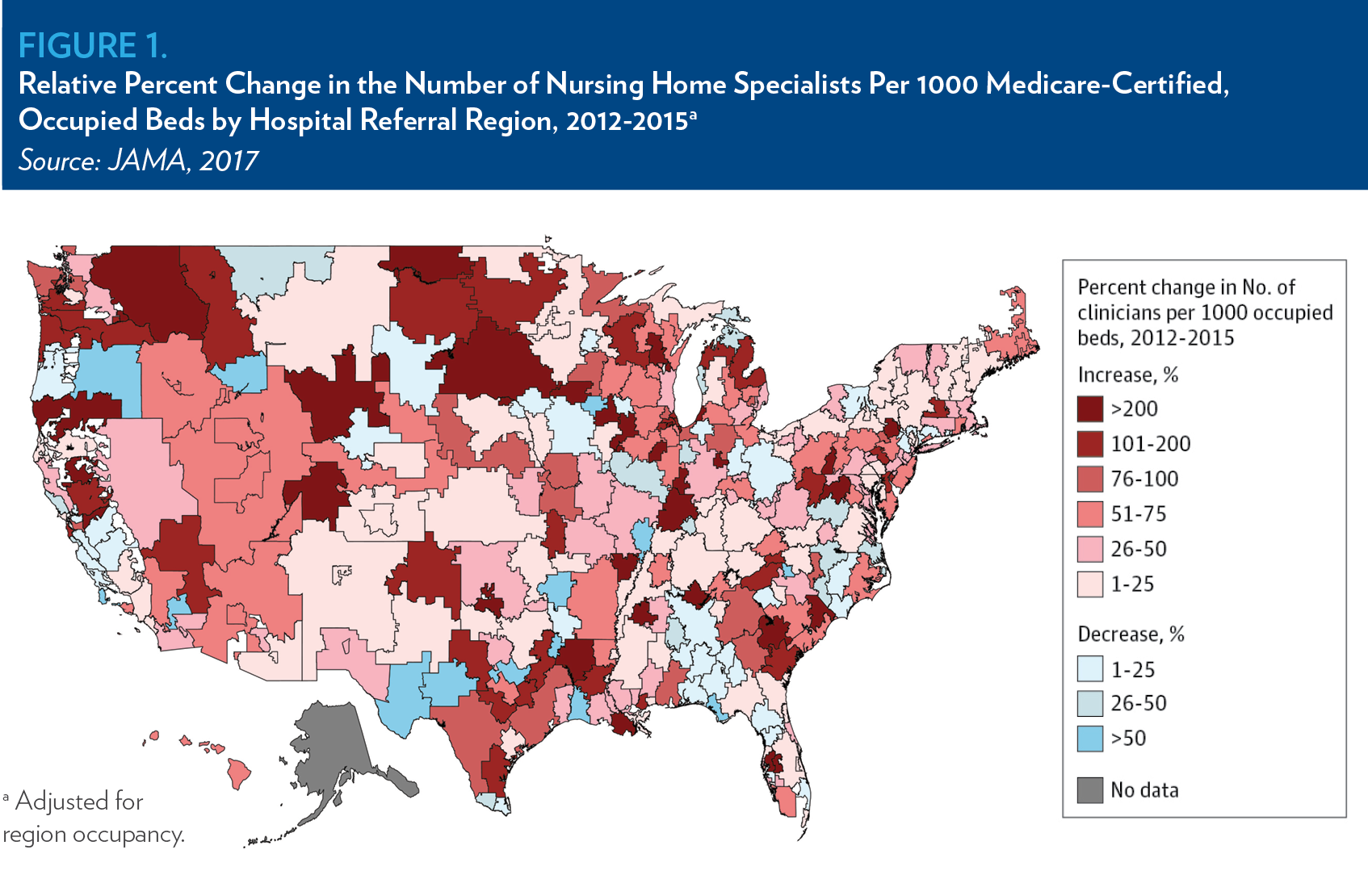

A 2017 JAMA research letter from LDI senior fellows Kira Ryskina, Dan Polsky and Rachel Werner measured the prevalence of nursing home specialists in the US between 2012 and 2015. In that paper, a nursing home specialist was defined as a generalist physician, nurse practitioner or physician assistant that provides at least 90% of billed care in nursing homes. This contrasts with the traditional model of care in which clinicians may ‘follow’ their patients who’ve been admitted to nursing homes, spending a couple of hours a week treating patients there. Although specialists only accounted for 1 in 5 clinicians practicing in nursing homes in 2015, they provided a disproportionate share of visits to patients. The number of these specialists in the United States grew by 33.7% between 2012 and 2015.

This trend is not uniform across the country. While 80% of hospital referral regions saw an increase in specialists, some regions saw no increase – or even a decrease – in nursing home specialists between 2012 and 2015. For example, while the number of specialists per occupied nursing home beds in parts of North Dakota and Washington increased by more than 200%, some regions in Texas and Oregon saw a decrease of more than 50%.

There may be some advantages to nursing home specialization from a patient perspective. By focusing on a narrower set of patients, specialists may develop additional expertise in the specific clinical and psychosocial challenges nursing home patients experience. Additionally, the ongoing presence of specialists in nursing homes may lead to improved communication with administrators, patients, and their families. These qualities, in addition to their familiarity with navigating the unique logistics of nursing homes, could make specialists more efficient at providing high quality care. If so, we’d expect to see improved outcomes, such as lower hospital readmissions, in patients receiving care from a specialist.

The first evidence we’ve seen on this topic shows a trend toward (mostly) better patient outcomes and marginally higher costs. In their recent study, Ryskina and colleagues found postacute care patients treated primarily by nursing home specialists were less likely to be rehospitalized (-1.5% absolute difference) and more likely to be successfully discharged into the community (+0.8% absolute difference) than those treated by non-specialists. Medicare payments between the two groups of patients differed unsubstantially over 60 days: $31,628 (specialists) vs $31,292 (non-specialists) on average.

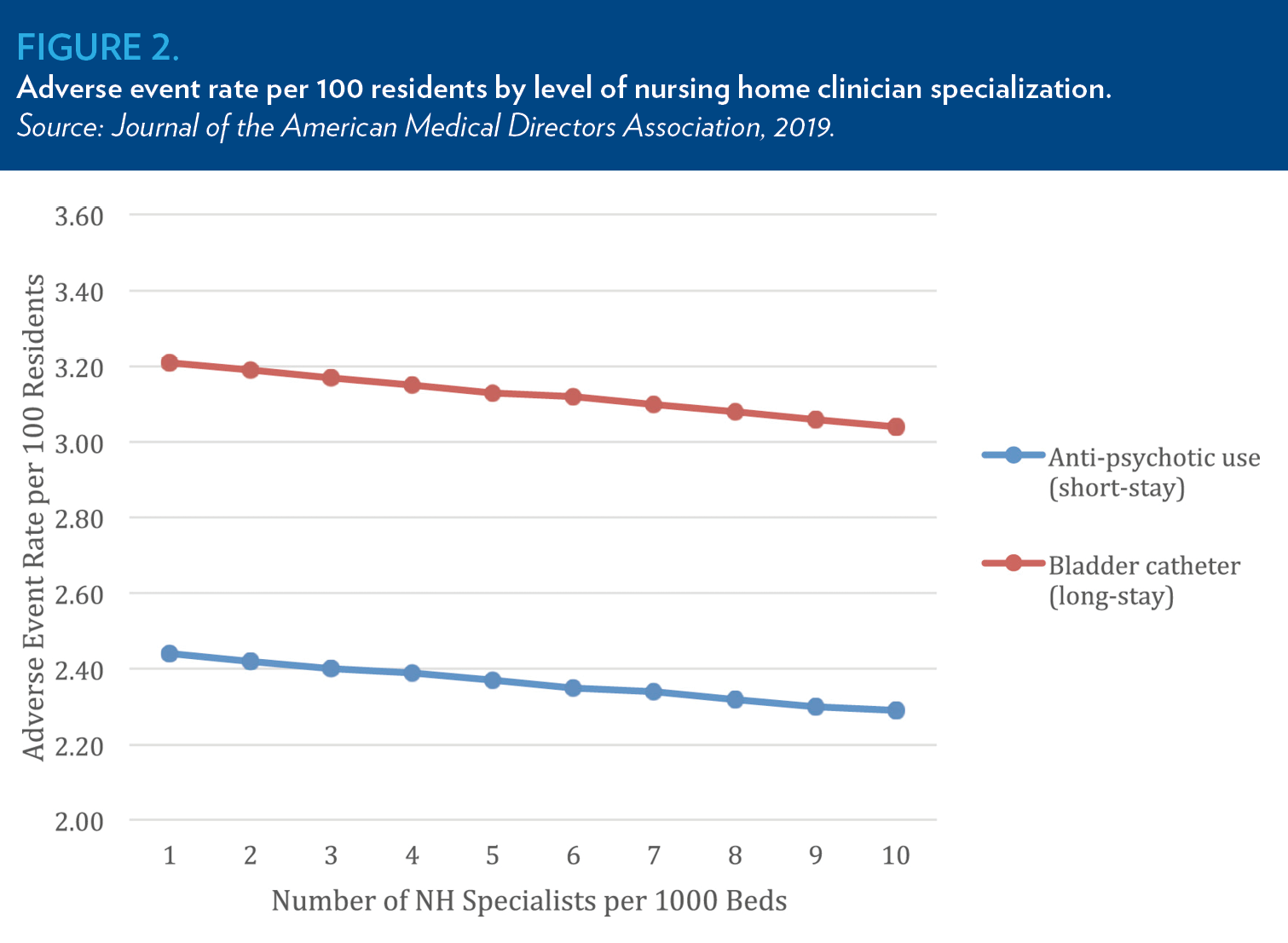

Another study from Ryskina compared nursing home clinical quality measures in hospital referral regions with a higher and lower prevalence of nursing home specialists. Between 2013 and 2016, regions in the top decile of nursing home specialization reported 5% fewer short-stay patients prescribed antipsychotics and 6% fewer patients with indwelling bladder catheters compared to regions in the bottom decile of specialization. Additionally, regions with a high prevalence of physician nursing home specialists reported significantly lower use of antipsychotics during short stays. Given a recent study finding that half of U.S. nursing home residents receiving antipsychotics did not have an approved indication for treatment, this suggests care provided by these specialists may be higher value.

On the flip side, the researchers found a link between increased depressive symptoms among nursing home patients and a higher regional prevalence of nursing home specialists. A possible explanation for this finding is that specialists could be more attuned to and likely to report depressive symptoms among their patients. Nevertheless, the relative influence of nursing home specialists on clinical outcomes in this study was low compared with other factors (such as direct care staff hours), and analyzing data at the regional level precluded the evaluation of some variables that may influence care quality.

Whether or not a trend toward specialization in the nursing home setting will be a good thing for patients remains an open question. It’s important to recognize that current evidence represents the tip of the iceberg in our understanding of a burgeoning field that will likely continue to develop in the years to come. Further study of this area will be important for determining if the trend toward specialization among nursing home clinicians endures, and, if so, whether or not this development is leading to a meaningful improvement in the quality and costs of care.