Blog Post

What’s In A Name: Will BPCI-Advanced Hold Back Or Advance Bundled Payment Policy?

Amol Navathe and colleagues on the Health Affairs Blog

[Reposted: Amol S. Navathe, Rebecca E. Anastos-Wallen, Ezekiel J. Emanuel, Joshua M. Liao. What’s In A Name: Will BPCI-Advanced Hold Back Or Advance Bundled Payment Policy?, Health Affairs Blog, February 5, 2018. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20180131.50449/full/: Copyright ©2018 Health Affairs by Project HOPE – The People-to-People Health Foundation, Inc.]

On January 9, 2018, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Advanced (BPCI-Advanced), a forthcoming Medicare bundled payment program that pays physicians and health care organizations for a defined episode of care, instead of individual services, to encourage clinicians and hospitals to improve quality and lower costs.

Prior to the announcement, the future of bundled payment programs under the Trump administration appeared unclear. Former secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Tom Price and CMS administrator Seema Verma were openly critical of several mandatory bundled payment programs designed under the Obama administration. Under their direction, mandatory models aimed at bundling cardiac care were cancelled and an existing orthopaedic joint replacement model was substantially scaled back.

Along with these policy shifts, however, HHS also indicated openness to continuing bundled payment through voluntary participation. The administration left the voluntary BPCI program in place, which represents the largest bundled payment program by any payer to date. HHS also implied a continued focus on bundled payment as a cornerstone alternative payment model, noting that a new voluntary program would be on the horizon. BPCI-Advanced is that program.

BPCI-Advanced And BPCI

As its name implies, BPCI-Advanced aims to build off of its predecessor BPCI and carry forward Medicare’s mission to “align incentives among participating health care providers for reducing expenditures and improving quality of care for Medicare beneficiaries.”

The two programs share a number of features. Both are voluntary programs that pay for all care associated with a set of specific clinical episodes. Both allow hospitals or physician group practices to assume responsibility for bundles of care, with emphasis on inpatient hospital care for orthopedic and cardiac conditions. Bundling is permitted through the same set of enhancements and incentives for example, waiver of the three-day hospital stay requirement for skilled nursing facility payment) in both as well.

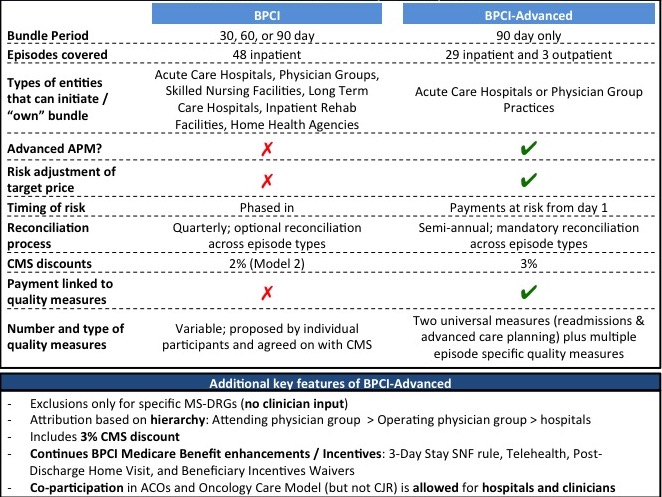

However, BPCI-Advanced diverges from BPCI in several substantive ways (Exhibit 1). Some changes represent improvements that will advance bundled payment policy, while other differences are missed opportunities or steps backwards.

Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Comparison tables of bundled payment models. Baltimore (MD): CMS; 2018 Jan.

How BPCI-Advanced Could Make Bundled Payment More Effective

BPCI-Advanced reflects continuity in Medicare’s approach to reining in health care spending using alternative payment models. The forthcoming program also clarifies the current administration’s commitment to bundled payment over the next five years, which is particularly notable in light of the early evidence that bundled payment can generate savings. Beyond that, BPCI-Advanced also pushes forward bundled payment policy in several specific ways.

First, it establishes the first-ever outpatient episodes, which are likely to be high-volume and high-savings opportunity areas for Medicare. The inclusion of these bundles addresses concerns about the “hospital-centricity” (that is, eligibility limited to inpatient hospitals only) of prior bundled payment programs.

Second, BPCI-Advanced qualifies as an advanced alternative payment model under the Medicare Access and Chip Reauthorization Act (MACRA) of 2015. It allows participants to engage in value-based transformation via a range of clinical conditions or procedures and makes them eligible for a meaningful 5 percent increase of professional fee payments. Ultimately, this designation strengthens the alignment between the BPCI-Advanced and national value-based payment transformation efforts.

Third, the new program accounts for patient case-mix by risk adjusting the target price, the benchmark price against which costs are measured. While more details are pending, this change is a welcome departure from BPCI and other prior programs (such as the scaled-back but ongoing mandatory joint replacement bundled payments program, Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement), which did not include risk adjustment beyond primary diagnoses. These programs were therefore easily susceptible to gaming from providers who could “cherry pick” lower-risk patients and exclude higher-risk patients from bundles.

How BPCI-Advanced Could Hold Back Bundled Payment Policy

Unfortunately, certain components of BPCI-Advanced may prevent the program from improving quality and reducing spending to its full potential.

First, even as it represents continued commitment to bundled payment overall, the program does little to improve coordination between bundled payment programs and other prominent alternative payment models such as accountable care organizations. Aligning payment models—and in particular avoiding of duplicative or counteracting incentives—will grow increasingly important as more Medicare beneficiaries receive care under them. Rather than augmenting incentives by allowing patients to be in multiple alternative payment models simultaneously with modified reimbursement, BPCI-Advanced continues the stepwise approach used in prior programs, excluding patients that fall under other payment models.

Second, despite Medicare’s stated goal to create payment models that are more physician-oriented, BPCI-Advanced does not appear to make progress toward this goal. Instead of creating physician-focused models, it largely replicates the approach used in BPCI that simply allows for simultaneous participation of hospitals and physician groups. Moreover, BPCI-Advanced removes the clinician-developed list of exclusions used in BPCI, a change that appears to be less, not more, physician-oriented.

Third, clinicians and organizations participating in BPCI-Advanced will work with Medicare on financial reconciliation (for example, determination of bonus payments or penalties) semi-annually. More timely reconciliation can increase the salience of financial incentives and the likelihood that clinicians and hospitals respond to them. A change from quarterly reconciliation in BPCI to semi-annual in BPCI-Advanced represents a step in the wrong direction.

Fourth, although it aspires to improve upon BPCI by requiring participants to meet quality measures, BPCI-Advanced misses the mark. For example, readmissions reductions are inherently incentivized through the financial structure of bundled payment (that is, reducing readmissions reduces episode use and spending). It is unclear what practice change or incentives are added by setting readmissions as a core quality measure across all episodes. The other core quality measure that spans episodes—advanced care planning—is only clinically relevant in certain conditions.

Questionable quality measure selection has important programmatic implications. Without comprehensive quality measures to ensure appropriate use and safeguard Medicare beneficiaries from unintended consequences, BPCI-Advanced would weigh financial incentives over quality or parity. One potential improvement and way to address this issue would be to require shared decision making across preference-sensitive episodes, such as orthopedic joint replacement or outpatient percutaneous coronary interventions.

Fifth, a major benefit of bundled payment is the ability to target incentives to the group of physicians primarily responsible for the care delivered over a defined episode. However, whereas BPCI afforded participants the option to apply financial reconciliation across episodes, BPCI-Advanced requires it. In other words, physicians participating in one episode (for example, cardiologist in the percutaneous coronary intervention episode) are penalized for poor performance by others in the participating organization (for example, orthopedic surgeons in joint replacement episodes). Not only does this design run contrary to hospital care delivery, which occurs through defined specialties and service lines, it also weakens incentives and their salience to clinicians.

Finally, by choosing a path that excludes testing of bundled payment through mandatory participation, Medicare is overlooking the problems inherent to voluntary programs. In particular, assessing the impact on cost and quality in a generalizable way will be challenging and may preclude a definitive answer on whether bundled payments are suited for expansion to the entire Medicare population.

Final Thoughts

Given the Trump administration’s earlier retreat from bundled payment by the cancelation of mandatory bundles, the announcement of BPCI-Advanced is welcome news to proponents of value-based payment reform, as well as clinicians and organizations considering bundled payment. However, there is more to advancing policy than a name. In several important areas, BPCI-Advanced misses opportunities to maximize the impact of bundled payments for participating physicians, health care organizations, and affected patients alike. Policy makers should address these issues as organizations around the country weigh and prepare for participation in BPCI-Advanced.