Health Equity

News

The Afterlife of a Controversial Scientific Debate

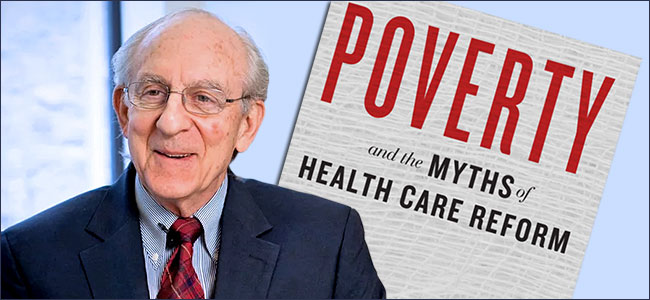

Buz Cooper's New Book as Finale Research Paper

Richard (Buz) Cooper, MD, would not back down when he was alive and now, his new book published posthumously catapults him beyond the grave in his ongoing philosophical assault on the prevailing assumptions that underpin much of the Affordable Care Act.

Published in August, the new book from Johns Hopkins press — “Poverty and the Myths of Health Care Reform” — is a 300-page, data-rich argument about why the late Cooper’s views are accurate and other scientists are not.

Primary driver of excessive health costs

Cooper, who died of cancer in January, is a former Penn Medicine oncologist who later morphed into a renowned health policy analyst at Penn’s Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics (LDI). His new book contends the currently dominant view — that the primary drivers of variation and excess health care costs across geographic regions are physician induced demand, entrepreneurial pricing, waste and fraud — is wrong.

Cooper’s hypothesis is that the primary driver of excessive health care costs is directly related to the number and density of the “poverty corridor” populations that sprawl across such large sections of the country’s metropolitan areas.

His contention is that the Affordable Care Act is exclusively focused on reducing costs by reducing waste, low-value care and treatment pricing with a complicated national overlay of new rules, measurement standards, payment procedures, incentives and penalties focused on these cost drivers.

‘At the core of America’s high health spending’

“Sadly,” Cooper writes, “the role that poverty plays in health care spending was not considered in formulating (the ACA’s) conceptual framework. In fact, it was denied. Yet,… poverty is at the core of America’s high health care spending. This may have eluded policymakers, but it confronts physicians, nurses, and hospital administrators daily as they cope with poor patients, whose high burden of disease and high rates of health care utilization overwhelm the system.” This is a point Cooper and scientists at the Dartmouth Atlas Project have debated back and forth for some time.

The eleven chapters of the Cooper’s book seek to peel the onion of poverty-related health care costs as viewed from Cooper’s interpretation of ZIP code and Hospital Referral Regions (HRRs) data in places like Milwaukee.

Cooper uses overlays of ZIP code income maps to identify “poverty corridors” — the neighborhoods with the densest population of low-income residents.

He reports that one-quarter of the residents in Milwaukee’s largest poverty corridor “lack adequate social and emotional support, which is double the state average.” They also lack convenient access to supermarkets and medical facilities. Hospital utilization in the corridor is “about double the rate” of other areas. Among other trends, it has the highest rate of hospitalization for obstetrical complications.

‘A direct reflection’

“This,” Cooper writes, “is a direct reflection of the characteristics of the poverty corridor, an area in which mothers are poor, mostly single, many are in their teens, and a high percentage do not receive early prenatal care. It is not difficult to understand why the infant mortality rate is high or how the high health care spending caused by social factors adds to the total costs of health care in the community.”

“Low income and related socioeconomic factors such as failure to complete high school and lack of social support are clearly associated with high levels of disability and greater amounts of health care utilization,” he continues.

Cooper notes that within HRRs, poverty is so heavily concentrated that the poverty corridor ZIP codes of low-income neighborhoods can be conveniently cut out for separate analysis. Overall, this found that “utilization was 35% greater in the Milwaukee HRR than in other Wisconsin HRRs.

“Most of this increment,” he writes, “was due to very high rates of admission for chronic diseases, such as congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and diabetes, which were fourfold to sevenfold more frequent among residents of the poverty corridor than among those residing in Milwaukee’s affluent suburbs.”

‘Stunning observation’

“However,” he says, “the stunning observation is that when the poverty corridor is removed from consideration, hospital utilization in the remainder of the Milwaukee HRR was no different than in other HRRs in Wisconsin.”

“Poverty,” Cooper said “is not just a major contributor (to excess costs). The high rates of hospital utilization in Milwaukee’s poverty corridor entirely explain the (spending) difference between Milwaukee and other Wisconsin HRRs. If Milwaukee were able to lift the lives of its poor and near-poor residents, hospital utilization could decrease by as much as 35%.”

Using this same analytical approach, Cooper’s book flies the reader across the poverty corridor utilization disparities of Los Angeles, New York, Boston, New Haven, southern Florida and other sections of the country.

He notes that the U.S. is the world’s highest-cost health care system at the same time it consistently ranks poorly on the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s list of countries’ comparative health measures.

High prevalence of U.S. poverty

“There are two principal reasons that health care is more costly in the United States,” Cooper writes. “First, and most readily understood, is that prices are higher. Second, but least appreciated, is that poverty is more prevalent. Compared with other OECD countries, the United States has more people who are low-income and socially disadvantaged, who tend to have greater need for health care services, but whose social circumstances and prior life experiences diminish the effectiveness of care and whose access to the kinds of social services that might enhance their life changes is disproportionally low.”

“The inescapable conclusion,” Cooper says, “is that solutions to America’s high health care spending do not lie in reengineering the fundamental structures of its health care system or in limiting the availability of its care. They live in strengthening elements of our economic and social infrastructure that would enable the poorest members of society to experience healthier lives and, ultimately, draw less upon health care resources.”

Related Items

Panel Discussion Honoring Richard A. “Buz” Cooper, MD

“Healthcare Workforce Policy: Balancing Quality, Costs and the Impact of Poverty”