News

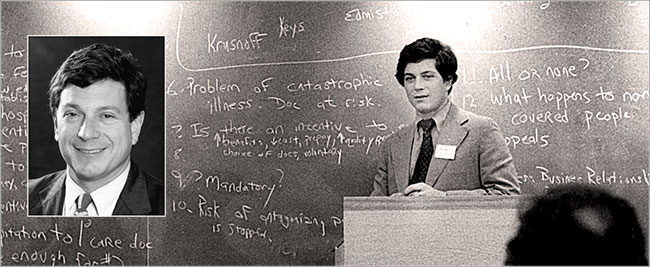

Beyond ‘John of AHRQ’ — John Eisenberg at Penn Medicine, Wharton and LDI

A Profile of One of the True Greats of Health Services Research

When Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Director John Eisenberg was struck down by brain cancer in 2002 during his fifth year in that post, it was a major emotional moment for the health services research field that viewed him as one of its most inspiring and influential leaders. The aching sadness expressed in an outpouring of academic journal memorials and remembrances during the rest of that year was also tempered by a communal sense of regret about what could have been.

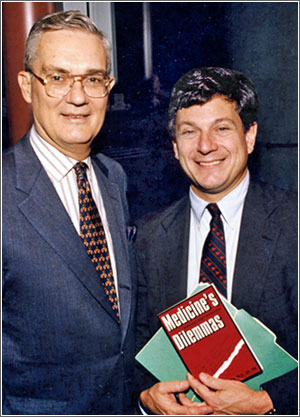

“I think John was on track to become the Health and Human Services Secretary with perhaps a stop-over as Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Administrator,” said University of Pennsylvania Wharton School Professor and LDI Senior Fellow Arnold Rosoff.

Rosoff, a Professor Emeritus of Legal Studies and Health Care Management who joined Penn in 1968, was Eisenberg’s teacher and publishing collaborator when the freshly minted MD and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholar was in Wharton’s Health Care Management MBA program in the 1970s.

‘Larger than life’

“John was as exceptional a student as he was a person,” said Rosoff. “It wasn’t just his intellect and drive. He had a kind of larger-than-life personal charisma similar to that of a Ted Kennedy or a John McCain that touched people, pulled them in, and made them excited about whatever he was excited about. He was very special.”

Indeed, a broad range of leaders across the highest levels of academia, government and business mourned his passing and hailed his extraordinary accomplishments. In an article titled “A Remarkable Legacy of Science,” Medical Care, a journal of the American Public Health Association, called Eisenberg “a true scientist as well as a practicing primary care physician [who] brought an evidence-based approach, a fundamental understanding of the nature of science, and a clinical sense of what patients and their providers needed to improve the quality of care and its outcomes. AHRQ blossomed under his guidance, developing a strategic plan for enhancing the science of assessing health care and fostering methods to improve the health care system and the people it serves.”

Writing in Health Affairs, Sen. Edward Kennedy, then Chair of the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee, noted “there are few in this world who can say that their work has helped millions of people have fuller, better lives. But John was in that extraordinary group of people who have done so much for so many. He has left a very special mark on the AHRQ. For those who really know, AHRQ has done for health services research what the NIH has done for biomedical research. In the long run, he made a great difference in people’s lives.”

LDI 50th Anniversary

As part of its 2017 50th Anniversary celebration, LDI is spotlighting a number of its former directors, students and researchers like Eisenberg who have gone on to careers characterized by significant health services research achievements. Although nationally best known for the last five years of his career in federal service, Eisenberg was heavily involved with LDI from his earliest days at Penn as a student in both Penn’s RWJF Clinical Scholars program and the Wharton School Health Care Management MBA program, both of which have long been closely affiliated with LDI.

He quickly became an LDI Senior Fellow and was invited to join LDI’s Executive Committee, whose members then included Samuel Martin III, William Kissick, William Pierskalla and Sankey Williams. In 1981, as a member of the Executive Committee of LDI’s National Health Care Management Center, Eisenberg participated in the two-day meeting at LDI that brought together the federal government’s top health services research managers. That gathering approved a plan to create the independent national health services research organization that would later change its name to AcademyHealth. Ten years later, while still at Penn, Eisenberg became the first physician to become President of that organization.

After spending the first 20 years of his medical career at Penn, Eisenberg moved to become Chairman and Physician-in-Chief of the Department of Medicine at Georgetown University.

‘John of AHRQ’

In 1997 he was named Director of the government’s highest health services research agency that was then under political siege threatening its defunding and closure. Eisenberg reorganized and resurrected the nearly moribund AHRQ, making it a vibrant national champion of evidence-based medicine and care quality — a success that earned him the moniker “John of AHRQ.”

More seriously, he became so politically adept and respected in the highest federal government circles that, for a time, as detailed by former JAMA Editor-in-Chief George Lundberg, he simultaneously served as both ad hoc U.S. Surgeon General and Assistant HHS Secretary both those positions were temporarily rendered vacant by Capitol Hill politics. Lundberg declared that his achievements and leadership skills had made Eisenberg the country’s “Top Doc” — a term originally coined a decade before by the media to describe C. Everett Koop, who revolutionized the Surgeon General’s office.

EISENBERG’S INTEREST AREAS

The areas of research and interest for which John Eisenberg is best remembered include:

- Modifying the practice behavior of physicians.

- Making evidence-based medicine the touchstone of health care policy, practice, and management.

- Establishing general internal medicine as a legitimate partner in academic medicine.

- Enhancing the assessment and control of health care quality.

- Strengthening and expanding health services research training and career development.

- Addressing health care disparities of race, ethnicity, income and sex.

During his two decades at Penn, Eisenberg was a clinical scholar, an LDI Senior Fellow, an innovative researcher willing to pursue uncommon topics, a beloved Penn Medicine professor and mentor, and ultimately, a highly influential faculty member who played a pioneering role in the creation of Penn Medicine’s Division of General Internal Medicine of which he was the founding chief.

~ ~ ~

Born to a family of modest means in Atlanta, Georgia, John Meyer Eisenberg grew up in Memphis, Tennessee, one of four sons of a department store men’s clothing buyer. His early life was made all the more traumatic by the loss of his father to brain cancer in 1971.

During his elementary and high school years in the late 1950s and early 60s, Memphis was one of the country’s most segregated cities with educational, social and commercial institutions regulated by laws that prohibited African Americans from “Whites Only” public places and services.

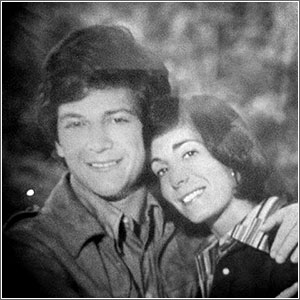

“We were sheltered from it,” remembered DD Eisenberg, John’s high school sweetheart who later became his wife of 32 years. “Memphis was so segregated that we didn’t have any interactions with blacks. I remember as a youngster going into a store and asking my mother about the ‘Colored Water.’ I didn’t understand what it meant.”

She also remembered that her high school, which was under court order to desegregate, didn’t have a prom during her senior year because the class included three African Americans. She said the school administration decided to cancel the dance rather than allow blacks to attend.

As the young couple left Memphis to attend college — he to Princeton in 1964 and she to the Missouri Journalism School in 1965 — the Civil Rights movement led by Martin Luther King Jr. was engaged in ever-larger protests in cities across the south.

Civil rights protests

“John had never been north of the Mason-Dixon Line before Princeton,” Mrs. Eisenberg said. “Getting away gave him a new perspective that there was a black/white, rich/poor dichotomy in Memphis and he got more involved with the idea of what medicine could do for people who couldn’t afford to get medicine. From that he drifted toward the larger issues of Civil Rights and took part in a lot of Civil Rights protests at Princeton.”

During this same period, the leader of that national movement, Martin Luther King Jr., was regularly in the headlines. At a Chicago news conference in 1966, for instance, he called for government action to force doctors and hospitals to comply with the Civil Right Act and desegregate their practices and admission policies. The Associated Press headline was “King Berates Medical Care Given Negroes.”

King told reporters, “We are concerned about the constant use of federal funds to support this most notorious expression of segregation. Of all the forms of inequity, injustice in health is the most shocking and most inhumane because it often results in physical death.”

Just weeks before Eisenberg graduated from Princeton with a degree in history in 1968, Martin Luther King was assassinated on the balcony of a Memphis Hotel by a racist sniper.

Devastated by MLK’s murder

“Like the rest of us,” said Mrs. Eisenberg, “John was totally devastated by King’s killing — especially the fact that it happened in our hometown. He was in despair. I remember he contacted people back in Memphis saying he wanted to try to get work in a medical clinic or do something else that would honor Martin Luther King when he came back home to Memphis that summer.”

“In his later career, I don’t think most people really knew that John was from the South; some were shocked to hear that he was from Memphis,” said Mrs. Eisenberg. “But there was a lot of Memphis in him. We grew up on grits and ribs and greens and he loved those. When he was sick, that’s the comfort food that people would bring him. He also grew up on Memphis Blues and he loved that music along with jazz for the rest of his life.”

In 1972, after receiving his MD from the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri, John and DD Eisenberg headed to Philadelphia where he began his residency at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP) in the primary care track and she became a news reporter at the now-defunct Philadelphia Bulletin newspaper.

Primary care track

“People were always curious about why he went the primary care route because so many others were going the specialist route,” said Mrs. Eisenberg. “Some told him ‘primary care is death row, you’re committing professional suicide’. But that’s what he and Sankey Williams were determined to do.”

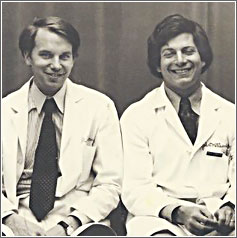

Williams, MD, was one of Eisenberg’s closest friends at Penn. Both men were residents, RWJF Clinical Scholars and students in the Wharton School’s Health Care Management MBA program. Williams is an LDI Senior Fellow and a Professor of both Medicine at Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine and Health Care Management at the Wharton School.

Along with all the other things he did during his 20 years at Penn, Eisenberg displayed a continuing interest in directly providing care to patients from low-income and racial minority communities in neighborhoods surrounding the Penn hospital. His wife remembers how he “kept hanging on to his group practice patients, who were predominantly African American women. He loved these patients and they loved him.”

After his death three decades later, he was lauded for playing a major role in pushing the broad issue of health care disparities to center stage in the world of both academic research and public policy. In its 2002 tribute, the journal Medical Care said, “Under John’s leadership, AHRQ emerged as a principal voice advocating for scrutinizing, understanding, and ultimately eliminating disparities in health and health care delivery. Consistent with these goals, AHRQ funded research that directly addressed gender and/or ethnic differences in health care processes and outcomes as well as research on vulnerable patient populations.”

AHRQ health disparities focus

During the last three years of Eisenberg’s tenure as agency chief, AHRQ supported nearly 200 major research grants and contracts related to health disparities.

An example of just one of them was a five-year, $45 million package in 2000 to fund research in the areas of “Racial and Ethnic Variation in Medical Interactions,” “Overcoming Racial Health Disparities,” “Improving the Delivery of Effective Care to Minorities,” “Access and Quality Care for Vulnerable Black Populations” and “Health Disparities in Minority Adult Americans.”

All in all, the record shows that the emotionally stricken Princeton grad who 35 years previous hoped to do something to honor the memory of Dr. Martin Luther King during that awful summer of 1968 had, in fact, continued that quest for the rest of his life.

~ ~ ~

As a HUP resident, LDI researcher and Wharton MBA student in an era when cost containment was emerging as a major health care concern, Eisenberg became interested in understanding the physician decision making process involved in ordering unnecessary care. In 1976, he published a study in the journal Clinical Chemistry documenting how a certain blood clotting test was being ordered for 87% of all new admissions at a Veterans Administration medical center even though only a small percentage of the admitted patients had a condition that warranted the tests.

A year later he published a related study in the Journal of Medical Education detailing his effort to determine the kinds of communication that might convince the same VA resident physicians to cease ordering the unnecessary clotting tests. The experiment employed posters, small conference meetings and mailings designed to change physician behavior. The strategy initially worked as the number of new admissions receiving those tests dropped from 87% to 55%. But in a follow-up 18 months later, Eisenberg found the pattern of overutilization had returned to its previous high level.

Physician behavior modification

“The major lesson to be learned,” he wrote of his findings, “is that an education program may have temporary effects, but without a continued program, physicians will probably lapse back into their old habits. The principles of behavior modification would predict such a result, since newly-learned behavior generally requires reinforcement to become installed as a regular part of behavior.”

A year after that as a student in Rosoff’s Wharton School course, Eisenberg wrote a term paper arguing that physicians should be responsible for the cost of the unnecessary medical services they order. Rosoff thought the paper was exceptional and helped Eisenberg turn it into a co-authored New England Journal of Medicine article. It concluded, “when overutilization is detected (by PSRO review), the patient often must pay the bill for costly unnecessary services… [We propose] to share the financial risk among parties other than the hapless patient. We propose that the physician, who has long been well rewarded financially, share this risk.”

“Physician decision making and overutilization,” said Williams, who collaborated with Eisenberg on some of this research, “were topics John got interested in early and never let go of throughout the rest of his career. His body of work in this area — papers, reviews, a book — played an important role in forwarding the idea that instead of just talking about this as a policy issue, we could actually collect data and treat it like any other clinical data; we could draw conclusions about physician decision making based on data rather than opinions.”

In 1981, Williams and Eisenberg collaborated to produce a grand overview of the subject as known at that time entitled “Cost Containment and Changing Physicians’ Practice Behavior: Can the Fox Learn to Guard the Chicken Coop.” Still regarded as a landmark paper, it emphasized that up to 80% of health costs are controlled by physicians and said “despite physicians’ power and responsibility as the patient’s representative in purchasing medical care, few physicians seem to know what it costs.”

~ ~ ~

Eisenberg’s most institutionally enduring project at Penn was his involvement in the creation of the Division of General Internal Medicine.

In the 1960s and 70s, changes in technology, bio-medical knowledge, training curriculums and patient demographics were coming together in ways that pushed ever larger numbers of med students toward lucrative specialist practices. This was depleting academic medical centers’ supply of primary care teachers as well as clinicians, creating serious new challenges for hospital managers. In the late 1960s, five teaching hospitals across the country were testing a new kind of “general internal medicine” unit focused on the recruitment, training and clinical integration of primary care doctors.

In 1974, then-Chairman of the University of Pennsylvania’s Department of Medicine, Arnold Relman, MD, convened a Committee on General Medicine to begin planning for HUP’s own general internal medicine division. It was an enormously complex undertaking that would potentially impact nearly all departments and have to be negotiated through a gauntlet of hospital traditions and logistics.

The working group selected a year later by new Department of Medicine Chief Martin Goldberg, MD, had 11 members, including 29-year-old HUP resident, Wharton MBA student and LDI Senior Fellow John Eisenberg, MD, and his similarly credentialed colleague, Sankey Williams, MD.

Founding GIM chief

Three years later, in August of 1978, the working group completed its plan and the new HUP General Internal Medicine unit was launched with Eisenberg — newly-named to a full professorship — as its first chief.

One of the common questions — and battles — academic centers then faced when creating these divisions was whether they should be exclusively focused on clinical tasks or enjoy broader mandates of academic teaching and scientific research duties. At Penn, Eisenberg championed the latter — and won.

“John’s great contribution,” said Williams, “was creating a division based on research AND teaching — the most important currency and credentials in the academic setting. He showed that a general medicine division could stand up with the cardiologists and nephrologists and infectious disease people and get the grants and write the papers and introduce the new ideas that attract the brightest of the bright medical students. Most other [academic medical centers’] divisions of general internal medicine were nearly all clinically oriented service departments delivering care but not generating papers or grants.”

“During the time John was Chief,” Williams continued, “when you asked almost anyone in medicine ‘which is the best general medicine research program in the country?’ they would have said ‘Penn.’ He’s the reason that today’s Penn Division of General Internal Medicine is one of our university’s most vibrant centers of education and high-level research as well as care.”

– – –

Hoag Levins is Editor of Digital Publications at the University of Pennsylvania’s Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics (LDI) and a former reporter and editor at newspapers and magazines in Philadelphia, New York and Washington, D.C.