Substance Use Disorder

News

Kit Delgado ‘Nudge’ Study Lowers ED Opioid Prescribing via EMR Defaults

Latest in both "Nudge" Work and Collaborative Penn Initiatives Related to Opioid Issue

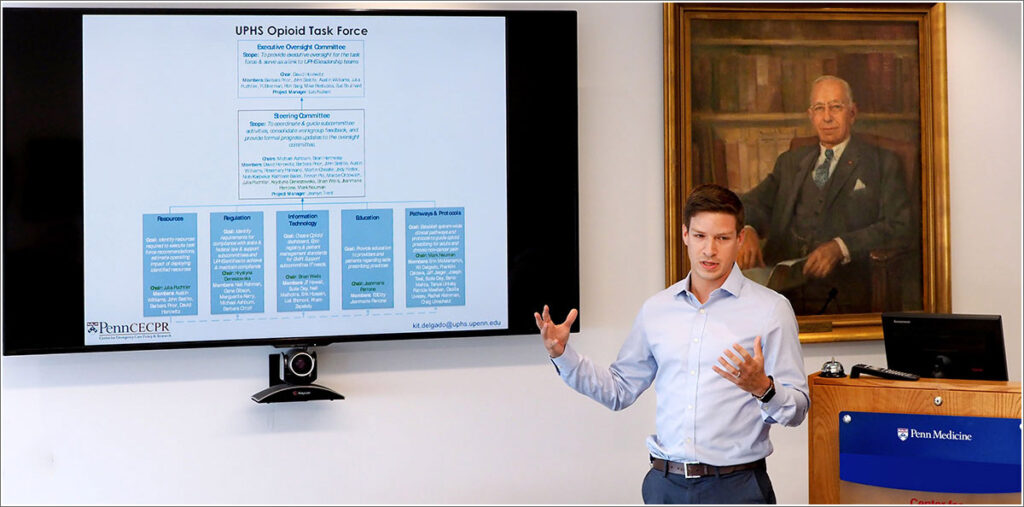

Penn Medicine researcher and LDI Senior Fellow M. Kit Delgado presents the findings of his opioid study to committee of Penn behavioral scientists.

A new study led by Penn emergency medicine physician and LDI Senior Fellow M. Kit Delgado has shown that slight “nudges” in the default settings of two large urban hospitals electronic medical records (EMR) systems can effectively lower the number of opioid pills prescribed by ED physicians.

The findings are the subject of an article in the Philadelphia Inquirer which also notes that Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf last week declared the state’s substance abuse crisis an official emergency. A recent University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy analysis estimated that the state had 3,900 overdose deaths in 2016.

Prescription of excessive amounts of opioid medications by clinicians has previously been identified as one of the factors driving the current national epidemic of opioid addiction and drug overdose mortalities. In its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report published last March, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said “The probability of long-term opioid use increases most sharply in the first days of therapy, particularly after 5 days or 1 month of opioids have been prescribed.”

Number of pills

In the past, it has been common for emergency department patients to be prescribed 30 or more opioid pills at a time. The latest ED prescribing guidelines suggest no more than 10 or 12 pills, although physicians are still free to prescribe more.

Published this week in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, the new Delgado-led study, “Association Between Electronic Medical Record Implementation of Default Opioid Prescription Quantities on Prescribing Behavior in Two Emergency Departments,” sought to determine if setting the details of the digital medical records system could increase the number of times the lower number of pills were prescribed.

The result over the 41 weeks of the investigation was that the proportion of prescriptions written for 10 tablets increased from 20.6% to 43.3%.

Delgado, MD, MS, an Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine at Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine and emergency medicine physician at Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, told Penn Medicine News “prescribing too many opioid tablets for acute pain increases a patient’s risk for long-term use or the potential to be abused if left in the medicine cabinet, so making it easier to prescribe quantities consistent with current guidelines while still keeping physician autonomy is an important part of addressing the opioid crisis we’re facing in this country.”

Multiple ‘nudge’ studies

The work is the latest in a growing body of “nudge” studies focused on drug prescribing and other aspects of the clinical environment fostered by Penn Medicine’s creation the Penn Medicine Nudge Unit, the first behavioral studies unit established inside a major health system.

In a related development in November, Penn Medicine researchers and LDI Senior Fellows Amol Navathe and Mitesh Patel received a $600,000 grant from the Donaghue Foundation for further studies of how best to reduce physician opioid prescribing in 50 emergency departments and urgent care centers affiliated with 24 hospitals operated by the Sutter Health System throughout northern California.

The CHERISH project

And yet another Penn opioid crisis initiative is the NIH-funded Center for Health Economics of Treatment Interventions for Substance Use Disorder, HCV, and HIV (CHERISH) that is a collaboration of LDI, Cornell University’s Weill Cornell Medical College, the Boston Medical Center and University of Miami Miller School of Medicine.