Health Equity

News

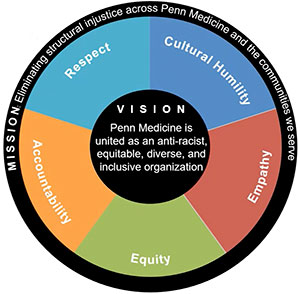

Penn Medicine Implements Anti-Racism Program Across Health System

Debuts New Anti-Racism Award at Martin Luther King Jr. Health Equity Symposium

Speaking on the third day of Black History month, in the post-George Floyd era of COVID disparities, Penn Medicine’s CEO, Medical School Dean, and Vice Dean of Inclusion and Diversity announced the implementation of a new institution-wide program aimed at eliminating structural racism.

As part of their appearance in Penn’s annual Martin Luther King, Jr. Health Equity Symposium, CEO Kevin Mahoney, Dean Larry Jameson, and Vice Dean Eve Higginbotham detailed the new Action for Cultural Transformation (ACT) initiative designed to “develop strategies to ensure equity, mitigate bias, and eliminate racism at Penn Medicine.”

Inflection point

“This year has been an inflection point,” said Dean Jameson, MD, PhD. “We’ve seen an outpouring of a deep understanding of the biases and structural racism in our society. And I think we’ve come to recognize that it’s important for all of us not only to look at the external society, but to look internally at our own organizations.”

CEO and LDI Senior Fellow Mahoney said, “Dr. King’s ability to turn the Montgomery bus boycott into a civil rights movement is exemplary of what we want to achieve with ACT at Penn Medicine: to turn moments of sickening injustice against people of color into a movement that will unite us as an anti-racist, equitable, diverse and inclusive organization.”

“The ACT movement is still in its beginning phase,” Mahoney continued, “but it’s one that has already brought about real change. We will approach this work the same way we’ve always done for the last 250 years to benefit those we serve and to do it together.”

Vice Dean and LDI Senior Fellow Higginbotham, SM, MD, ML, who heads the Penn Medicine Office of Inclusion and Diversity, explained that “ACT is a grassroots effort. This is not top down. This did not start in Dean Jameson’s or the CEO’s office. This came from you. We heard over 5,000 voices as part of this process and synthesized 160 recommendations into the program. You can also see the many solidarity statements we’ve received on the ACT section of our website.”

New Penn Medicine award

Also inaugurating a new feature of the MLK Health Equity Symposium, Mahoney announced the first annual winner of Penn Medicine’s Champion of Inclusion, Diversity and Equity Award: The Department of Family Medicine & Community Health Anti-Racism Task Force (ARTF). Founded in 2019 by a small group of faculty and residents, ARTF now has 60 members, including residents, faculty, clinical support staff, researchers and administrative personnel.

“The Task Force has developed meaningful interventions to significantly increase the amount of underrepresented minority candidates interviewed to become residents working together to increase diversity,” said Mahoney. “This will ultimately lead to better outcomes, better patient satisfaction and a more diverse faculty and workforce.”

He noted that the Task Force has also advocated for equitable COVID-19 testing at Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, and addressed disparities through the removal of race-based anemia guidelines. It is also working closely with the Department of Pathology and Nephrology on removal of the race-based version of the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) test for kidney function.

Photo: Britannica

Keynote Dorothy Roberts

Keynote speaker of the Symposium was Dorothy Roberts, JD, FCPP, Penn PIK Professor of Africana Studies, Law, and Sociology; Director of the Penn Program on Race, Science & Society, and author of a number of books, including Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics, and Big Business Re-create Race in the Twenty-first Century.

She spoke on an aspect of Dr. King’s work that hasn’t gotten a lot of attention: his philosophy about the relationship between science and religion and justice.

“In a series of sermons, he pointed out that people had ‘twisted the insights of religion, science and philosophy to give sanction to the doctrine of white supremacy,'” said Roberts, quoting from Dr. King’s 1963 collection Strength to Love. “‘The idea was embedded in every textbook and preached in practically every pulpit.’ He was talking about how white supremacy became part of the scientific, religious and social culture of America, and how it was embraced ‘not as a rationalization of a lie, but as an expression of a final truth.'”

Science and race

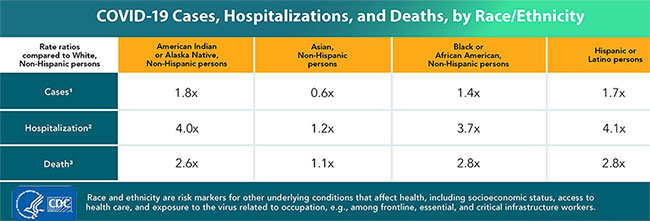

“Science and religion promoted the false idea of biological races and the superiority of the white race over other races. Today, these false ideas are promoted in debates about COVID-19 and its devastating impact on African-American communities. Some scientists claim there might be some unknown or unmeasured genetic or biological factors, suggesting something innate in Blacks and people of color that causes them to have higher rates of infection and death.”

“Another view, however, which I believe to be correct, is that it’s not about some innate racial difference but rather about the long-term impact of structural racism and the social determinants of health,” said Roberts.

Justifying slavery

“Dr. King pointed out that men convinced themselves that a system of slavery ‘that was so economically profitable must be morally justifiable.’ Science provided the justification by claiming human beings were divided into races and that white people were at the top of a racial hierarchy. This system viewed Black people as closer to being animals than to being human being like Europeans.”

“Doctors were very important in promoting this and the idea of a racial concept of disease — that people of different races have different diseases and experience common diseases differently. This supported the false biological concept of race, because if nature created the races differently enough that we can distinguish one from the other, that means that it’s likely that their bodies function differently.”

“Nineteenth-century reports about the diseases and peculiarities of the Negro Race claimed Black people had lower lung capacity than white people and therefore had to be enslaved and forced to work by white people in order to be healthy.”

Innate disparity

“This led to the idea that racial differences in various kinds of body functions have to be measured in different ways because of an innate disparity between how bodies work, depending on their race,” Roberts explained. “The spirometer of the 1800s automatically corrected for assumed racial differences in lung capacity — Black people’s was assumed to be lower.”

“Today, this same thing is embedded in the test for kidney function or the estimated glomerular filtration (eGFR) rate in most hospitals. It’s still typical that the measure of kidney function is adjusted upward to a healthier number automatically if the patient is identified as African American.”

“So African-American patients are categorically and automatically given a different number for the same amount of the telltale protein in the blood then all other human beings. And because of recent research, we know that this has a harmful impact on black patients. It steers them away from specialty care and even can disqualify them for being put on a kidney transplant waiting list. In other words, if they weren’t black, they would get a number that would signal they should be seen by a specialist or would signal that they qualify to be on a waiting list for a kidney transplant,” said Roberts.

Human Genome Project

“In 2000, when the draft mapping of the human genome was unveiled at a White House ceremony, the scientists in charge and President Clinton all pointed out that it showed human beings were not genetically divided into races but were very much genetically the same — the vast amount of human genetic diversity isn’t divided into biologically distinguishable races.”

“In my book, Fatal Invention, I point out that despite these findings of the Human Genome Project, there was nevertheless a resurgence in defining race as a genetic grouping and looking for genetic explanations for racial inequities, combined with biotech and pharmaceutical companies producing race-specific remedies for these so-called biological differences.”

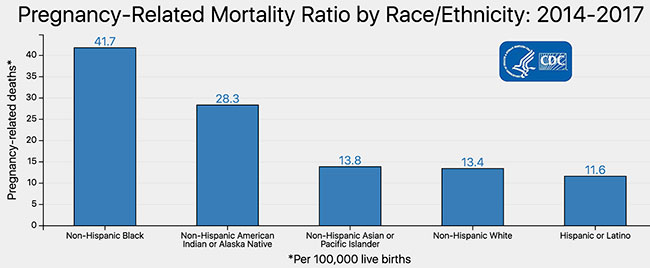

“For instance, some research continues to look at differences in maternal death rates and higher infant mortality rates among Blacks by exploring hypotheses that they are caused by ‘Black race independent of other factors’ — as if you can identify something called Black race and separate it from all other factors. But social factors are much more plausible explanations for why we see these disparities in health.”

“This also led to the development of race-specific drugs like BiDil, a drug for heart failure, that the FDA allowed to be marketed specifically for Black patients. The justification for it was that the FDA was using self-identified race as a surrogate for genetic markers, again promoting this idea that a self-identified race somehow is reflective of genetic differences.”

‘Poverty of the spirit’

“Dr. King pointed out that, in spite of the strides of science and technology, there was nevertheless ‘a poverty of spirit which stands in contrast to our scientific and technological abundance. We have learned to fly the air like birds and swim the sea like fish, but we have not learned the simple art of living together as brothers.'”

“For me, King’s message was that without justice, science and technology can separate us and not necessarily advance the health of everyone. A more equal and just society would be a healthier one.