Health Equity

News

Primary Care Access Mapped Across Entire City of Philadelphia

Study Finds Ten-Fold Variation in Geographic Availability

Geographic access to primary care facilities across the census tracts of the City of Philadelphia varies by as much as ten-fold, according to a new University of Pennsylvania study.

Commissioned by the Philadelphia Department of Public Health, funded by the local Independence Foundation, and conducted by a team of Penn health services researchers affiliated with the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics (LDI), the project was the first of its kind in the country’s fifth-largest city. The final report is titled Location Matters: Differences in Primary Care Supply by Neighborhood in Philadelphia.

Researchers identified all primary care practices in Philadelphia and calculated the population-to-provider average to be 863:1 or 863 adults for every primary care provider. Overall, that average is a healthy one, according to national benchmarks.

Lopsided pattern

But on a census tract-by-census tract analysis of physician locations, researchers found a very lopsided pattern in which primary care providers cluster heavily in some areas and very sparsely in others. The data indicates that the highest-access neighborhoods in the city have ten times more adults per provider than the lowest access neighborhoods.

Lead author Elizabeth Brown, MD, said, “it is a critical time to measure primary care in Philadelphia because it represents an indicator of ability to deliver better population health from the sweeping reforms the Affordable Care Act has set in motion.”

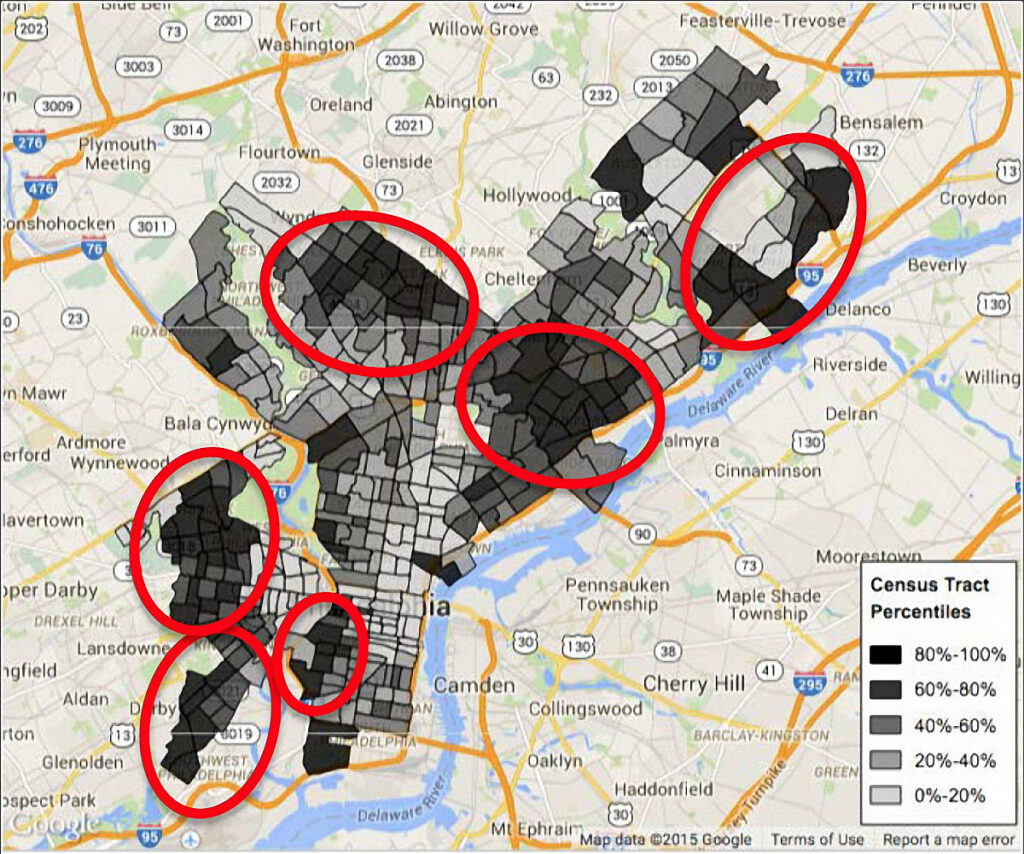

One of the many maps in the Penn study report released today shows six red circles around the areas of least primary care access in the city.

Six lowest access areas

When researchers matched these six clusters against U.S. Census Bureau data for Philadelphia’s population-by-race, they found that in three of the six areas of lowest primary care access 75% or more of the residents are African American. In a fourth, the African American population was 62%. A fifth circle in the city’s Lower Northeast had a majority population of African Americans and Hispanics. The sixth circle in the city’s Greater Northeast section had the lowest percentage of non-white residents but higher median age.

Brown cautioned that the study findings should be read narrowly and are only about geographic access to primary care facilities. Related Resources Location Matters: Differences in Primary Care Supply by Neighborhood in Philadelphia The Full 59-page Report Location Matters: Differences in Primary Care Supply by Neighborhood in Philadelphia The Full 6-page Executive Summary Study Author’s Blog Post

First of Its Kind Project Other LDI Primary Care Access Research Projects

A Synopsis of Policy and Practice Analysis

“We looked at where populations and primary care physicians are located; the findings don’t necessarily mean that people in these areas aren’t able to access primary care,” said the Penn Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholar and LDI Fellow. “Residents in one area may travel to another to access primary care.”

Further research needed

She emphasized that further research work is needed to tie the patterns of geographic primary-care access to actual patterns of health outcomes and other health care-related measures.

“Important next steps,” Brown said, “would include studies of primary care wait times and how different kinds of insurance or lack of insurance may affect the ability to get appointments in various areas.”

Institute of Medicine (IOM) landmark reports in 1988 and 2003, and a similar white paper from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) stress that it is now an essential job of state, county and municipal health departments to monitor the health care system in more detail, document the many ways that system engages (or fails to adequately engage) local populations, and make that information available to local health care delivery stakeholders and the public.

Lack of data and infrastructure

The Penn study’s executive summary starts off by noting that “Implementation of the Affordable Care Act has increased the number of Americans with health insurance and raised concerns about the capacity of the primary care workforce. Despite the importance of insurance access to health care, most local health departments do not have the data or infrastructure to monitor the availability of primary care.”

Aside from gathering and analyzing that data for the first time in Philadelphia, the project’s goal was to establish and validate a system and method that would enable the local health department to conduct ongoing monitoring of geographic primary care access patterns throughout all Philadelphia census tracts.

“Comprehensive data about where primary care physicians are located has previously been hidden from view or otherwise not readily available,” said study co-author David Grande, MD, MPA, who is Director of Policy at LDI and an Assistant Professor of Medicine at the Perelman School of Medicine.

Changing role

“Historically, local health departments have played a larger role in directly delivering care but today local governments are less likely to do so,” Grande said. “But health departments should absolutely be involved in monitoring the health services available in their region. This study is very relevant to that latter role.”

“In this new era of the Affordable Care Act,” he continued, “local hospitals face increasing accountability for conducting community health needs assessments and the methodology we document in this report could help them to make those assessments more accurate and meaningful.”

“For instance, in terms of primary care access, we’ve known for a long time that northeast Philadelphia has a problem,” said Grande who’s been a practicing physician and health services research scientist in Philadelphia for 12 years. “The main signal for that has been the incredibly long wait times at the city-run health center there. It can take as long as six months to get a new patient appointment.”

“What we haven’t had in the past,” he continued, “is clear signals about other parts of the city. But now several of the clusters identified in our study show where a deeper look is needed to assess potential problems. Our project is essentially a pointer directing the local health care establishment toward those areas it needs to pay closer attention to.”

The study-funding Independence Foundation is a private, not-for-profit philanthropic organization whose mission is to support organizations that provide services to people who do not ordinarily have access to them.