News

Is The Threat of COVID Vaccine Hesitancy Getting Enough Attention?

Penn LDI Experts Weigh in on the Latest Developments - or Lack Thereof

Splashy news coverage of the first wave of COVID-19 clinical vaccine trials has triggered a similarly high-profile debate about “Who Should Be First?” to get the vaccine when it does become available. But there is one equally important question being asked much less frequently: what happens if not enough people get vaccinated to establish the herd immunity crucial to ending the pandemic and returning the country and its economy to some semblance of “normal”?

This latter concern is widely shared throughout the highest levels of the national public health community.

(Photo: Aspen Ideas)

Herd immunity ‘unlikely’

Speaking in late June at the annual Aspen Institute’s Ideas Festival, which brings together leading minds from around the world to discuss health and other global issues, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Director Anthony Fauci, MD, acknowledged the first versions of a COVID vaccine would only be 70-75% effective. He went on to say that level of effectiveness, paired with the fact that one-third or more of the U.S. population doesn’t intend to get vaccinated, makes it “unlikely” the U.S. will reach sufficient levels of herd immunity.

The latest scientific assessment of this probability arrived earlier this month in a special report from the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security and Texas State Anthropology. Its nationwide team of 23 epidemiologists and behavioral scientists concluded that unless critical steps are taken by federal and state governments to address vaccine hesitancy, “a future COVID-19 vaccination campaign may fall short.”

‘A real and present danger’

Entitled “The Public’s Roles in COVID-19 Vaccination,” the Hopkins/Texas State report came out just weeks after the Sabin Vaccine Institute and Aspen Institute’s “Meeting the Challenge of Vaccination Hesitancy” was released. That latter book-length report said, “COVID-19 arrived at a time when hesitancy about long-established vaccines has become a real and present danger.”

“It is a serious problem,” emphasizes University of Pennsylvania researcher Damon Centola, PhD, who wrote part of the Sabin/Aspen report. “Vaccine hesitancy has become politicized and, as a result, increasingly entrenched within specific communities.”

Network analysis expert

A professor at both the Annenberg School for Communication and the School of Engineering and Applied Science, Centola specializes in network analysis, and has pioneered an experimental online method for evaluating the effects of network structures on the spread of health and other behaviors, like vaccine hesitancy.

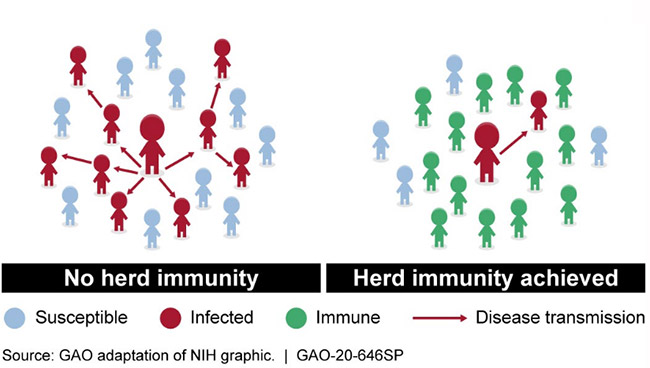

“The model of herd immunity works if a small number of unvaccinated individuals are randomly distributed throughout a population,” he said. “But if the members of a particular community coordinate on choosing not to vaccinate, then the entire community is vulnerable to an epidemic outbreak. Once a critical mass of infected individuals is reached, it enables a contagion to spread much farther throughout the rest of the population, even if a significant fraction of the population is vaccinated.”

What actually happens if the U.S. fails to reach herd immunity to the coronavirus?

“I don’t care to imagine it,” said Centola. “The clearest implications are rising death tolls, increased burden on the health care system — potentially to the point of rationing care — and, as a secondary result, a severe economic recession.”

Last year, just before COVID-19 hit, vaccine hesitancy was officially recognized by the World Health Organization as one of the top ten threats to global health. The widespread public backlash and distrust of a vaccine produced at “Warp Speed” has now increased the level of vaccine hesitancy further.

‘A contagion of doubt’

In his chapter in the Sabin/Aspen report, Centola explains how anti-vaccine propaganda is turned into credible beliefs by media-savvy communications activists exploiting social media and other venues to spread “a contagion of doubt” about vaccine safety. The goal is to repeat and echo their messages constantly through the media to turn junk science claims with no factual basis into a seemingly legitimate point of view.

Penn epidemiologist, vaccine hesitancy expert and LDI Senior Fellow Melanie Kornides, ScD, MPH, APRN, is worried. “I don’t think the public is fully aware of the link between misinformation and vaccine hesitancy. And I don’t think the public appreciates the implications of one third-to-one half of the population rejecting the vaccine.”

‘Dangerous advice’

“We have a large amount of both information and misinformation flowing across four levels of discourse — scientific, political and practice, news, and social media,” Kornides continued. “It becomes very hard for the public to discern which information is credible and which is not. This is increasingly difficult when political leaders give contradictory, and sometimes dangerous, advice.”

In a recent editorial using somewhat starker language, Science magazine Editor-in-Chief H. Holden Thorp, PhD, wrote “the scientific community is up against a sophisticated, data-driven machine devoted to making sure that science doesn’t fully succeed…there is a massive, churning, finely-tuned digital misinformation machine that has seized social media to ensure that a portion of the population doesn’t accept science; the scientific community is losing the battle against this digital leviathan of misinformation.”

There is a massive, churning, finely-tuned digital misinformation machine that has seized social media to ensure that a portion of the population doesn’t accept science; the scientific community is losing the battle against this digital leviathan of misinformation.

H. Holden Thorp

The Hopkins/Texas report recommends that “federal health agencies should develop a coordinated national promotion strategy, employing human-centered design to develop interventions that help a broad network of champions communicate effectively with the public about risks, benefits, allocation and targeting, and availability.”

CDC Director

CDC Director

Earlier this month, in testimony before the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, Robert Redfield, Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), said his organization is working on a plan to increase confidence in a COVID-19 vaccine, but provided little detail.

It’s not clear how much progress states or cities have made on their own in planning and producing educational and promotional campaigns to increase public confidence in a COVID-19 vaccine. When asked in June if Philadelphia was preparing educational and promotional campaigns focused on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among adult residents, Department of Health Communications Director James Garrow said, “Not at this point. Right now our focus in the Health Department is very much just on essentially what’s happening NOW. We are pulling ten and twelve hour days trying to get folks to wear masks and stay six feet apart. I definitely think that there is a concern that when we get to that point (of having a vaccine) we’re going to have to do work to sell this.”

Black community mistrust

The same month, Carmen Guerra, MD, MSCE, LDI Senior Fellow and Vice Chair of Diversity and Inclusion in the Perelman School of Medicine’s Department of Medicine, testified before a committee of Pennsylvania State senators investigating the impact of coronavirus infections throughout the region’s African American communities. She told legislators, “We have staff and experiences in the community that already tell us there’s misinformation circulating that makes many of our Black residents fearful of a COVID vaccine; makes them mistrustful of a vaccine.”

“I think we need to prepare for that with really accurate information and ways of disseminating information through people we trust,” Guerra continued. “Then, once a vaccine does become available, we should establish policies that provide for free vaccines.”

COVID racial disparities

Testifying at the same state senate hearing was Vice President of the Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR), former CDC senior Senior Behavioral Scientist, and infectious disease researcher, Gregorio Millett, MPH. He provided the legislators with a statistical overview of the coronavirus pandemic’s heavy impact on Black communities across the country:

“COVID-19 cases and deaths were higher in counties with a greater proportion of black residents than all other counties. Despite representing 22% of US counties and only 35% of the US population, disproportionally black counties accounted for 52% of COVID-19 cases nationally and 58% of COVID-19 deaths. Disproportionally black counties were also impacted earlier than other counties. We also found that it did not matter whether counties were in urban, small metropolitan areas or rural areas, COVID-19 cases were greater in communities with a higher number of black Americans.”

Centola and Kornides are among the many scientists worried about how this disparately high rate of African American COVID infection and mortality will intersect with that same community’s equally high rate of vaccine hesitancy.

‘Compounding inequities’

“This is a great concern,” said Centola. “And the issues surrounding it are subtle. For generations, the African American community has been subject to institutional discrimination and racism in health care. As a result of this history and its implications for vaccine hesitancy, its members are subject to greater risk from COVID-19 exposure. The danger of these compounding inequities is a primary concern for me, and I am currently developing several projects to study how to address health inequities that emerge as downstream effects of the history of discrimination and racism in health care. My belief is that using online and offline social networks to engage community members’ existing biases regarding public health information will be an important part of the solution to vaccine hesitancy.”

Kornides agreed. “This is the optimal time to get ahead of the misinformation surrounding the COVID-19 vaccine and protect the public against vaccine hesitancy. My group is working on a messaging strategy that can be deployed through social media and used to encourage vaccination acceptance and protect people from accepting dangerous, misinformed beliefs.”

Others point out that health services research’s evidence-based insights could be very relevant to this quest.

Behavioral economics

Writing in USA Today, a newspaper that has a national readership of 2.3 million, LDI Senior Fellows Katherine Milkman, PhD, and Mitesh Patel, MD, MBA, along with Angela Duckworth, PhD, MSc, discussed how behavioral economics principles might be brought to the task of increasing COVID vaccination rates.

Milkman is Professor of Operations, Information and Decisions at the Wharton School; Patel is Director of the Penn Medicine Nudge Unit at the Perelman School of Medicine; and Duckworth is a Professor of Psychology at the Penn School of Arts & Sciences.

“The good news is we don’t have to start from scratch,” the trio wrote. “We already have scientifically-tested ways to encourage people to make healthier decisions, and there are many more approaches to encouraging vaccination that haven’t been tested.”

“Pharmacies, health insurers, and health systems have an opportunity to collaborate with behavioral scientists on massive research efforts to learn what works,” the authors continued. “We should be testing everything from cash rewards to psychologically wise reminders delivered by text, email, snail mail, and phone. And we should be running these studies at an unprecedented scale given the hundreds of thousands of lives and trillions of dollars we stand to lose if the pandemic isn’t stopped as quickly as possible.”