News

A Cyber Solution to Barriers that Previously Thwarted Medical Food Distribution

LDI Senior Fellow Jaya Aysola Details Pilot Project’s Creation of a Central Digital Hub to Coordinate Regional Services

The idea that adequate food intake is a crucial element of a person’s medical conditions and overall health has gained a lot of traction in recent years. So has the suggestion that health systems and their clinicians have an obligation to somehow directly address this issue. But that concept turns out to be as easy to say as it has been challenging to achieve. While there are substantial numbers of community-based organizations (CBOs) like food banks and food pantries that distribute food and facilitate other social support services in any given city, they tend to be logistically and financially siloed from each other and difficult to coordinate into an efficient and stable city-wide medical food resource.

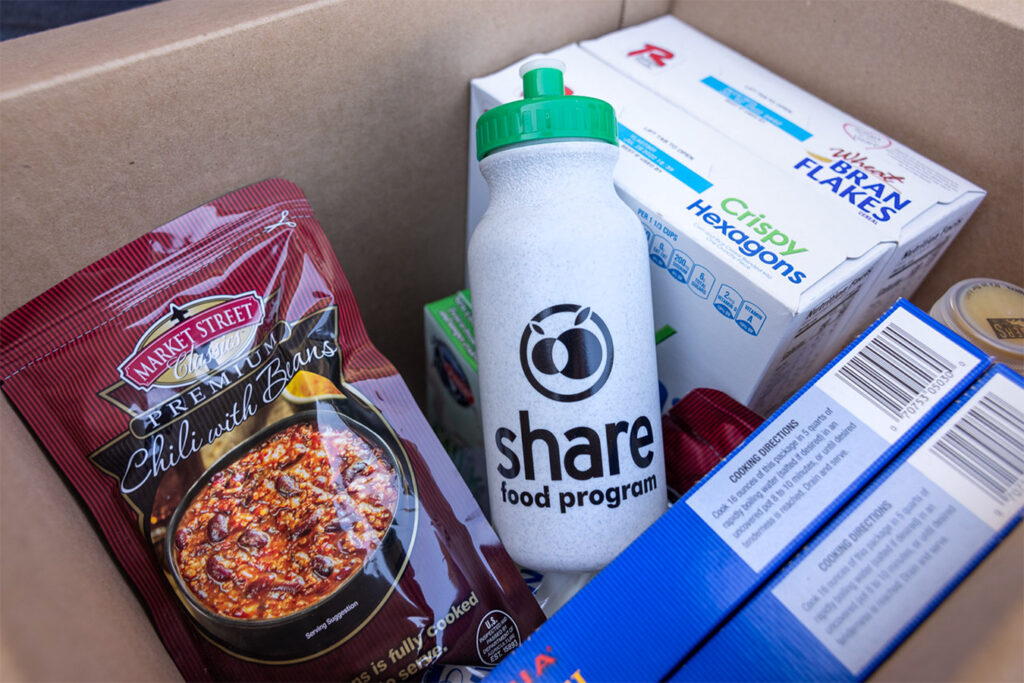

In a new study published in the July Journal of General Internal Medicine, LDI Senior Fellow and University of Pennsylvania Health System Associate Professor Jaya Aysola, MD, MPH, and her team detail how they set out to change this reality by developing a centralized digital platform designed to reinvent the communication and logistics of medical food delivery. The study’s title is “Food Access Support Technology (FAST): a Centralized City-Wide Platform for Rapid Response to Food Insecurity.” The platform directly links the University of Pennsylvania Health System, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and Jefferson Health with the region’s community-based social service organizations, food banks, and two food delivery companies.

The essential goal of the program is to immediately provide food to patients who need it during the period of waiting before they are connected to other longer-term benefit sources, such as COMPASS, the Pennsylvania State Department of Human Services’ application system that provides a wide range of social services, including food assistance programs and/or financial assistance programs that help individuals buy food.

With automated algorithmic match-up capabilities, the FAST platform centrally connects all participants in real-time ways that enable a care team member’s request for a food service for a patient to be entered, claimed, and filled with the first delivery to their home occurring within 24-48 hours. The same process previously took weeks and frequently broke down without knowing if the food was delivered to the patient. Since early 2020, the FAST pilot project has facilitated food services to over 1,700 households, reaching over 4,500 people.

Central Communications Hub

“We think the system is unique and are unaware of anything like it,” said Aysola. “We’re not merely servicing patients. We were working with the health systems and other players that were all grappling with similar needs and barriers. Now, they have a centralized hub they can access by desktop or smartphone to share resources and engage in real-time communications. It’s an environment that is dramatically different from prior operations, where organizations communicated by phone, fax, or in person. For example, this platform now provides an ability to get assistance and meet the needs of challenging cases in real time rather than retrospectively at monthly meetings that convene community organizations to discuss such cases and brainstorm about possible future solutions.”

Funded by the TD Charitable Foundation, FAST has now received additional support from the Equity and Access Fund, founded by Penn Medicine Associate CMO David Horowitz, MD. A Penn Medicine page facilitating donations to the project has also been established. As they continue to refine their model and evaluate its impact in areas like patient health outcomes, Aysola’s team believes the system has broad potential applications beyond Philadelphia.

“I think in cities where multiple health systems are tasking the same community-based organizations there also needs to be dedicated thought and effort to find better ways to collaborate on food distribution,” said Aysola. “This is particularly critical as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has mandated social needs screening for all inpatient admissions starting January 2024.”

How it Began

In an effort to address the problem in its own Philadelphia region in 2019, Penn Medicine established the Social Determinants of Health Enterprise-Wide Workgroup, with the Center for Health Equity Advancement (CHEA) as the convener. CHEA is headed by Aysola and her team, Rose Thomas MPH Director of Operations, Ana Bonilla Martinez BS, CHES Project Manager of their social accountability initiatives, along with Heather Klusaritz PhD, Director of Community Health Services. The CHEA team along with Patricia Meehan, LSW Deborah Lowenstein, LCSW and Preeti Advani, MSW, LSW from HUP Case Management and Social Work Department created the Social Needs Response Team (SNRT), a virtual resource staffed by social workers and medical students. Its initial research across the Philadelphia region found that local food banks had plenty of food but no way of getting it to elderly patients then quarantined by COVID-19 or other outpatients lacking transportation or otherwise isolated in their homes.

“The Social Needs Response Team was initially born out of necessity to bridge an educational mission as well as a service mission gap,” said Aysola. “We had a rise in patients with social needs at the same time we had a dearth of clinical-facing electives for medical students that needed elective time to graduate. We created this virtual team of social workers and medical students to directly help patients with their social needs and we got a huge uptake. We also started attending food insecurity working groups at the public health level around the region and it quickly became clear that we all needed a way of collaboratively communicating about these challenges and sharing messages and resources in real time.”

Social Needs Focused Team

That began the project that became the Food Access Support Technology (FAST) pilot in which Penn Medicine’s Social Needs Response Team continues to play a major role.

SNRT is a five-day-a-week operation staffed by medical and social work students and a licensed clinical social worker who work to determine and assist patients with their social needs, distress, or safety concerns.

When a care team member determines that a patient needs food, a request is entered into FAST, which goes through algorithmic permutations, returns a list of the community-based organizations that could match that request, and pushes a notification out to those organizations. The organizations are monitoring incoming requests on their own FAST dashboards and can “claim” a request they are capable of fulfilling.

Once claimed, the system automatically sends a notification alerting the user that the request has been accepted. Then, the request is processed, and a FAST request is sent to coordinate drop off to the patient’s home by the delivery service companies. When the accepted request has been fully completed, the system also notifies the person who submitted the request.

The health systems, community-based organizations and food banks participating in the FAST hub all have their own established financial resources but the critical element that doesn’t yet have sustained funding is the local Black-owned businesses that provide the home delivery services across the Philadelphia region.

“I think there are three reasons why private insurers and hospital systems will ultimately carry these costs,” said Aysola. “It’s been demonstrated that food provisioning reduces readmissions. There have already been some negotiations with insurers on rates for subsidizing patients’ food and transportation needs. So, there is a model for that on the private side. And I believe future studies will additionally confirm that providing social needs support improves outcomes and lowers costs.”

Aysola also believes that CMS’s intention to make the use of its Accountable Health Communities (AHC) Health-Related Social Needs (HRSN) Screening Tool mandatory for all inpatient admissions will provide a strong incentive for health systems to explore new technologies that pull together a region’s social resources and health providers in centralized ways similar to FAST.

CMS: Widespread Patient Food Insecurity

The CMS program she refers to was launched in 2017 by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation’s (CMMI). Called the Accountable Health Communities (AHC) Model, it was designed to test whether systematically connecting Medicare and Medicaid patients to community resources to address health-related social needs could improve health outcomes and reduce costs. Over a five-year period ending in 2021, it conducted the social needs screening of more than 1 million patients and found that the single social determinant of health cited by 63% — or over 600,000 patients — was food insecurity.

Author

Hoag Levins

Editor, Digital Publications

More Food Insecurity News

Expiration of the USDA Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Emergency Allotments

Increased Food Insufficiency Highlights Inadequacy of SNAP Benefits After Thrifty Food Plan Revisions

Senbagam Virudachalam Named to Food Trust Board of Directors

LDI Senior Fellow Deeply involved in Health Equity and Nutrition Research

Food Prescription Programs: Future Potential and Current Obstacles

Penn LDI Seminar Convenes a Panel of Top Food-as-Medicine Experts

In The Media VeryWell Health

Rising Food Insecurity Connected to Higher Cardiovascular Mortality, Study Finds

Interview