Can AI Hear When Patients Are Ready for Palliative Care?

Researchers Use AI to Analyze Patient Phone Calls for Vocal Cues Predicting Palliative Care Acceptance

Blog Post

Generative AI already helps clinicians interpret lab results, dose antibiotics, and respond to patient queries. The current approval processes for health AI use the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s software-as-a-medical-device (SaMD) framework, which works best for single-manufacturer tools designed to perform narrow tasks, like classifying high-risk lung lesions. But modern generative AI products have a broader skill set, and may be built on a foundation created by one company, fine-tuned by another, and extended via third-party plug-ins, with no clear regulatory accountability.

Penn LDI Senior Fellow Eric Bressman and co-authors propose, in a recent JAMA perspective piece, a different approach: licensing AI in much the way we license human physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants, who practice in supervised and collaborative ways.

Bressman and his co-authors argue that the concerns about generative AI, such as hallucinations and performance drift, mirror worries from the late 19th century about quack remedies and variable clinician training. Licensure’s approach, combining practice standards with ongoing surveillance and education, can be adapted for AI regulation.

Ideally, a new federal digital licensing board would oversee the framework, Bressman and colleagues propose.

But existing federal and state bodies could play important roles: the FDA could retain its role in premarket assessments, preventing developers from needing to submit to 50 state licensing authorities.

Designated health systems with AI expertise could function as implementation centers, and continuing oversight and discipline could fall to state medical boards, with a federal coordinating body to harmonize standards.

“A licensure framework may help ensure that innovation scales with accountability and not ahead of it,” the authors write. Below is a table showing parallels between clinician licensing and a potential future AI licensing structure.

| Licensure concept | Human clinician | Generative AI |

| Prelicensure requirements | Accredited degree, and passing national board examinations Supervised period of clinical training | Technical validation for predefined competencies (AI national board examinations) Supervised pilot in nationally accredited “implementation centers” (AI “residency”) |

| Scope of practice | Delineation of approved medical services, in which populations, with degree of autonomy Collaboration or supervision agreements for PAs/NPs | Delineation of approved functions (eg, image interpretation), in which populations, with degree of autonomy Guidance on supervising clinician oversight for each function |

| Institutional credentialing | Health systems credential to perform specific procedures and review outcomes and can suspend privileges for safety concerns | Health systems’ AI governance committees vet site-specific implementation, determine local privileges within the licensed AI’s scope of practice and monitor local quality metrics, can revoke a privilege or deactivate a model if thresholds not met |

| Continuing oversight | Continuing education requirements and periodic knowledge assessments (for maintenance of board certification) | Annual rerun of updated benchmarks for each competence and reporting of clinical performance measures for review by board |

| Discipline/liability | State medical boards investigate complaints and can fine, suspend, or revoke license, or mandate retraining Actions reported to the National Practitioner Data Bank Manufacturers, health systems, clinicians potentially liable | Digital boards receive and process complaints and can place AI system on probation; require model patches or additional guardrails; suspend or revoke license Maintain a public database of disciplined models and corrective action plans For a restricted license, or for higher-risk functions, supervising clinician and institution liable; with higher degree of autonomy (e.g., for lower-risk functions) developers become liable |

The piece “Software as a Medical Practitioner—Is It Time to License Artificial Intelligence?” appears in the November 17, 2025 issue of JAMA Internal Medicine. Authors include Eric Bressman, Carmel Shachar, Ariel D. Stern, and Ateev Mehrotra.

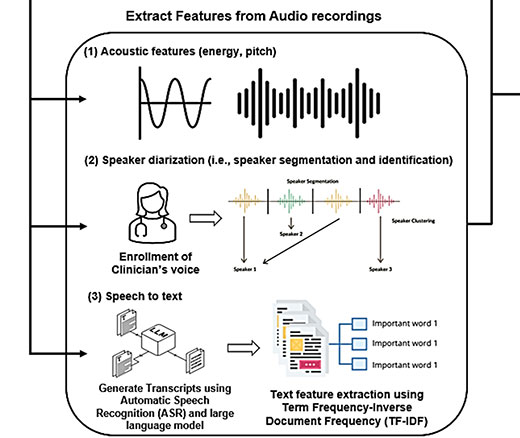

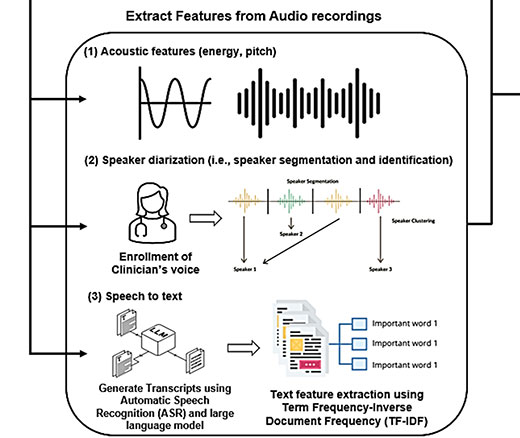

Researchers Use AI to Analyze Patient Phone Calls for Vocal Cues Predicting Palliative Care Acceptance

Study of Six Large Language Models Found Big Differences in Responses to Clinical Scenarios

Experts at Penn LDI Panel Call for Rapid Training of Students and Faculty

One of the Authors, Penn’s Kevin B. Johnson, Explains the Principles It Sets Out

More Focused and Comprehensive Large Language Model Chatbots Envisioned

2025 Penn Nudges in Health Care Symposium Focuses on the Human-Machine Interface