Patients Face New Barriers for GLP-1 Drugs Like Wegovy and Ozempic

Even With Lower Prices, Medicare, Medicaid, and Other Insurers Tighten Coverage for Drugs Like Mounjaro and Zepbound Using Prior Authorization and Other Tools

Brief

Community health centers (CHCs) are a bedrock of the social safety net in the United States, providing care to vulnerable people in their communities, often for little or no cost to them. CHCs operate through funding streams and reimbursement mechanisms that pose challenges to participating in newer forms of value-based payment. This issue brief provides a snapshot of CHCs and the people they serve, how they currently are funded and reimbursed, how they fit into the landscape of value-based payment, and how alternative payment policies can align with their mission and mandate.

As public and private payers move toward strategies that pay for value rather than volume, they rarely consider community health centers (CHCs) in the design of alternative payment models. These models seek to move away from paying providers for services or encounters and toward rewarding providers for measurable outcomes.

Value-based payments represent an opportunity to improve care to underserved populations and address health disparities, although most payment models have not focused on these goals.1

For more than 50 years, CHCs have provided comprehensive, coordinated primary care to medically underserved populations. Although CHCs face obstacles to participating in existing value-based payment models, these safety net providers represent a key constituency for achieving health equity goals and addressing health disparities. In this brief, we highlight the challenges in implementing value-based payment in CHCs, and promising ways to promote value-based care in these centers.

For our purposes, we define a CHC as a center that provides primary care in an underserved area or to an underserved population. Included in this definition are federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), FQHC look-alikes, and rural health clinics (RHCs). We exclude free and charitable clinics, an important part of the social safety net, because they operate largely outside of the health insurance system. Instead, they rely primarily on donations, grants, and a volunteer workforce.2

In 2022, 1,370 FQHCs served 30.5 million patients in more than 16,000 sites across the country. Some FQHCs are funded to serve specific populations, including 299 centers providing health care for people without housing, 175 serving migrants and seasonal agricultural workers and 175 delivering primary care to residents of public housing. Across all sites, FQHCs serve about one of six Medicaid beneficiaries. About two-thirds of patients identify as racial or ethnic minorities, including 38% Hispanic/Latino and 21% Black/African American. About half of all patients are covered by Medicaid, 11% are covered by Medicare, 20% have private insurance, and 19% are uninsured.9 In 2022, 117 FQHC look-alikes served about one million patients in more than 600 sites, with demographics similar to FQHCs.10 Compared to FQHCs, FQHC look-alikes see a smaller percentage of uninsured patients and slightly higher percentages of patients with Medicaid and private insurance.

Partly because RHCs do not receive federal Section 330 grants, there is far less information on RHCs and the demographics of their patient populations. In 2023, more than 5,200 RHCs served rural populations in 45 states. The centers are concentrated in the South and Midwest. About 65% of RHCs are provider-based, meaning they are part of a hospital, nursing home, or home health agency, while 35% are operated independently.11 Nearly three-quarters of independent RHCs are for-profit, compared to just 11% of provider-based RHCs. The National Association of Rural Health Clinics estimates that in 2022, RHCs served more than 37 million patients, representing about 11% of the entire population and about 62% of the 60.8 million people living in rural America.12

CHCs rely heavily on Medicaid and Medicare as sources of revenue, but the distribution of these sources varies by the type of health center. FQHCs receive substantial funding from the federal government to help cover the cost of providing free and reduced-cost care to their patients.

FQHCs receive about 12% of their revenues from Section 330 grants, which amounted to an average of $3.7 million for each FQHC in 2022.13 Figure 1 shows the various sources of FQHCs revenues. More than one-quarter of their revenues come from federal, state, and local grants and contracts, which complicates FQHC participation in alternative payment models. Because they do not receive Section 330 grant funding, FQHC look-alikes have a slightly different mix of revenues, with nearly 20% coming from private insurance. However, they also derive a significant portion of their revenues from nonpatient care sources, including 18% from grants and contracts (primarily state, local, and foundation grants). There is far less information on the precise distribution of revenue sources for RHCs, which do not receive federal grants and are not required to charge on a sliding fee basis. These sources will vary by whether the RHC is independent or provider-based. In general, RHCs are more reliant on Medicare revenues than FQHCs, because rural populations are older and reimbursement can be higher than Medicaid. In 2021, traditional Medicare paid RHCs more than $1.3 billion, covering almost 2.2 million individual Medicare beneficiaries and about 9.3 million visits. In contrast, traditional Medicare paid FQHCs $976 million, covering about 1.8 million beneficiaries and about 8.2 million visits.15

Acknowledging the important role of health centers in the safety net, Congress established special Medicare and Medicaid payment rules for FQHCs and RHCs.16 Instead of using a fee schedule for clinician services, Medicare and Medicaid pay FQHCs and RHCs a rate that generally bundles all professional services furnished in a single day into one payment. The FQHC and RHC payment bundles cover professional services but exclude other services commonly provided in conjunction with a visit, such as lab tests and imaging services. FQHC look-alikes are paid similarly.

While these special payment rules provide CHCs with enhanced funding, they can pose challenges to CHC participation in alternative payment models, especially those built on the fee-for-service chassis. Operationally, different billing and reconciliation systems can complicate the transition to value-based payments; financially, federal payment requirements may limit CHCs’ ability and willingness to take on financial risk.

Since 2014, traditional Medicare has paid FQHCs based on a per-visit national rate. The base rate was set on FQHCs’ reasonable historical costs, adjusted annually for inflation. In 2023, the base rate was $187.19. This rate is adjusted to reflect differences in practice costs across geographic areas. For a new patient or an annual exam, the rate increases by 34%. For Medicare Advantage (MA) enrollees, FQHCs contract with each plan, but they receive supplemental payments from Medicare to make up any difference between the traditional Medicare rate and what the MA plan pays.

State Medicaid programs have two options for paying FQHCs: programs pay using a prospective payment system (PPS) that includes a per-visit bundled payment, based on the historical costs; or they pay through an alternative payment methodology (APM). By federal statute, the APM must be at least what the FQHC would have received under its PPS per-visit rate (or the state must make up the difference), and the FQHC must agree to the APM. As of 2020, about half of the states use an APM to pay FQHCs for their Medicaid beneficiaries.18

Traditional Medicare pays RHCs a facility-specific rate for each visit, which is calculated annually by dividing the facility’s total allowable costs by the total number of visits.19 The payment rates and limits were changed significantly in 2021 to address historical inequities between independent and provider-based RHCs. The all-inclusive rate for independent RHCs and for provider-based RHCs that are part of a hospital with 50 or more beds is now subject to a national statutory payment limit, which was $126 in 2023. The national payment limit will be increased each year until 2028, when it will be $190. Historically, provider-based RHCs that were part of a hospital with fewer than 50 beds were not subject to the national statutory payment limit. In 2020, Medicare’s all-inclusive rate for these RHCs averaged about $255 per visit. However, since 2021, the payment limit per visit for these RHCs is equal to the greater of their 2020 payment rate (increased by inflation) or the national statutory payment limit.

For Medicare Advantage enrollees, RHCs negotiate rates with each Medicare Advantage plan. However, unlike FQHCs, there is no statutory requirement that Medicare make up the difference between what traditional Medicare pays and what the health plan pays. The National Association of Rural Health Clinics surveyed its members and found that about half reported that Medicare Advantage plans paid less than traditional Medicare.20

Like FQHCs, state Medicaid programs can pay RHCs through the PPS per-visit rate or through an APM. The RHC must agree to the method, and the reimbursement rate must be at least as much as would be paid under the PPS methodology.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, CHCs delivered most services in-person and could only bill Medicare for telehealth services if the patient was located at the clinic and the provider was in a different location. In response to the pandemic, however, federal regulations were relaxed, a move that has been extended through 2024. Many CHCs pivoted quickly to furnishing telehealth services to patients at any location, including their homes. One study found that nearly one-third of visits to FQHCs from June-November 2020 were conducted by telehealth.21

These changes had implications for CHC revenues because telehealth services (except for mental health visits) are not reimbursed at the standard bundled visit rate. Instead, they are paid a rate similar to comparable telehealth services billed under the Medicare fee schedule. In 2023, that rate was $98.27.22 The disparity between reimbursement for in-person visits and telehealth visits may be a barrier to continued use of telehealth, as by 2022, 87% of medical visits in FQHCs were conducted in-person.23 In contrast, mental health visits, when provided through interactive, real-time telecommunications, is reimbursed at a bundled rate and can be billed as a separate visit on the same day as a clinic visit. In 2022, 46% of mental health visits in FQHCs were conducted through telehealth.24

Medicaid reimbursement policies for telehealth vary by state. As of fall 2023, 37 states and District of Columbia reimburse FQHCs for telehealth services, including 25 states and DC that explicitly state that FQHCs can receive the PPS visit rate when serving as a distant site (that is, when the provider is located at the FQHC and the patient is not).25

One of the hallmarks of value-based payment is holding providers accountable for the quality of care they provide. That feature requires tracking and rewarding achievement of specific quality measures. CHCs often provide services to an entire community, and so clinical quality measures may not fully capture the value of what they provide. It is useful to think of value-based payment as one way to promote value-based care, in which care is designed (or redesigned) to focus on quality, provider performance, and the patient experience.26

FQHCs and FQHC look-alikes are required to report each year on a set of clinical quality indicators (see Table 2). Studies have consistently found that they perform as well as, if not better than, private practices on most metrics.27 In 2022, FQHCs performed better than comparable national benchmarks for four quality measures, including low birth weight, hypertension control, diabetes control, and dental sealants for children.28

A broader indicator of value-based care is recognition as a patient-centered medical home (PCMH), which reflects the presence of processes to improve access, continuity, and coordination of care.30 In 2022, 78% of FQHCs had been certified as PCMHs.31 Measuring quality in RHCs is more difficult because they are not required to participate in Medicare quality programs and do not report on a defined set of quality metrics. Further, the diversity of their ownership structures complicates the development of a set of metrics. In 2016, the Maine Rural Health Research Center piloted a small set of primary care-relevant quality measures for RHCs, including child immunization rates, diabetes and blood pressure management, tobacco use interventions, and documenting current medications.32 The study documented the feasibility of an RHC quality measurement system, as well as key barriers to RHC quality reporting, including data extraction difficulties from clinic records and limited staff time to collect and report data.

In the past decade, the federal government and many states have launched alternative payment strategies that hold providers accountable for the quality of the care they provide, rather than simply paying for the volume of care. These value-based payments can take many forms, including shared-savings, shared-risk, bundled payments, or population-based payments (see Figure 2).33 Many of these alternative payment strategies focus on care delivered in traditional Medicare. To the extent that these strategies are built on the architecture of fee-for-service payments, they are less relevant to CHCs that are paid through bundled, prospectively set rates. And they may be less attractive to FQHCs that derive only a small portion of their revenues from Medicare.

For example, in 2015 Medicare implemented its merit-based incentive payment system (MIPS) that adjusts clinician Part B payments based on certain quality performance measures, but the system is based on fee-for-service claims. FQHCs and RHCs are not required to participate in MIPS. In contrast, Medicare also implemented voluntary advance payment models, such as accountable care organizations (ACOs), in which groups of providers collaborate to coordinate care for traditional Medicare beneficiaries. Depending on the track, ACOs share in the savings and sometimes take on downside risk. CHCs can choose to participate in Medicare Shared Savings Program ACOs, and many have. As of 2023, more than 4,400 FQHC sites participated in a Medicare ACO, along with 2,240 RHCs.34 Medicare has recently implemented changes to its Medicare shared savings program that encourage participation of new ACOs, promote health equity, and support providers seeing rural or underserved beneficiaries.35

Meanwhile, as more and more state Medicaid programs implement APMs, some CHCs may see an APM as a means of overcoming deficiencies in the present system, including lengthy payment delays and lags in the reconciliation (wraparound) process.36 They also note that the COVID-19 pandemic drove home the fragility of a payment system heavily tied to the volume of face-to-face encounters, even in an age of telehealth. During the pandemic, contracts that involve capitated or other fixed payments helped sustain some CHCs as they curtailed in-person services and invested in telehealth.37 The Commonwealth Fund recently profiled several FQHCs that are participating in a range of Medicaid APMs, highlighting the need for a stepped approach that involves upfront funding for the data infrastructure and financial forecasting tools needed to succeed in APMs.38

In 2024, Medicare will launch a new model called “Making Primary Care” in eight states through a progressive, three-track approach to transforming care.39 It will provide a pathway for primary care clinicians with varying levels of experience in value-based care to gradually adopt prospective, population-based payments while building the needed infrastructure to improve care coordination, care integration, and community connection. It is the first model to explicitly include FQHCs and Indian health clinics, but it excludes RHCs.40 Across all tracks, FQHCs will continue to use the existing PPS methodology for reimbursement, which will be gradually shifted to a quarterly per-beneficiary-per month payment in later tracks.41 Although this program overcomes certain obstacles to FQHC participation in VBP models, the lack of a critical mass of Medicare patients may still prevent FQHC entry. One study found that less than half of all FQHC sites, nationally, would have enough attributed patients in traditional Medicare to meet the 125-patient threshold for eligibility.42

The RHC exclusion from this and other VBP models has prompted National Association of Rural Health Clinics to call for a model of a value-based payment specific to RHCs, one that would include small subset of easily reported outcomes measures, and would augment the current all-inclusive rate payment methodology, rather than replace it.43,44

CHCs are well-positioned to deliver value-based primary care, particularly in underserved areas and to underserved populations. Many already have a population-based focus, provide coordinated and integrated care, and assess and address social determinants of health. However, they face significant obstacles to participating in current VBP models for the following reasons:

Given these obstacles, it is worth considering other strategies to advance value-based care at CHCs. Because many CHCs serve a significant portion of uninsured patients and draw significant funding from grants and contracts, individual payer-based strategies may not be optimal for these kinds of providers. Instead, nonfinancial incentives such as accreditation or certification could be paired with financial rewards to promote value-based primary care in these settings. Such a strategy could also be used by funders to promote value-based care in the more than 1,400 free and charitable clinics that serve a largely uninsured population. As an example, recognition as a PCMH has become a standard of care for FQHCs, signaling the delivery of patient-centered care and achieving standards of care coordination and ongoing quality improvement.45 Some public and private payers have linked this recognition with financial incentives or bonuses. Multi-payer strategies that reward CHCs for delivering coordinated, comprehensive primary care to all patients may be the most promising way to promote value-based care, in a system that acknowledges the critical and unique role CHCs play in our social safety net.

This issue brief was produced in conjunction with a project supported by the Independence Blue Cross Foundation Institute for Health Equity.

Even With Lower Prices, Medicare, Medicaid, and Other Insurers Tighten Coverage for Drugs Like Mounjaro and Zepbound Using Prior Authorization and Other Tools

A 2024 Study Showing How Even Small Copays Reduce PrEP Use Fueled Media, Legal, and Advocacy Efforts As Courts Weighed a Case Threatening No-Cost Preventive Care for Millions

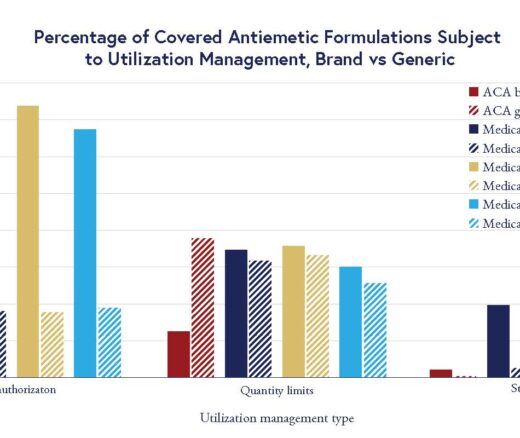

Chart of the Day: LDI Researchers Report Major Coverage Differences Across ACA and Medicaid Plans, Affecting Access to Drugs That Treat Chemo-Related Nausea

Insurers Avoid Counties With Small Populations and Poor Health but a New LDI Study Finds Limited Evidence of Anticompetitive Behavior

A Proven, Low-Risk Treatment Is Backed by Major Studies and Patient Demand, Yet Medicare and Insurers Still Make It Hard To Use

Chart of the Day: Medicare-Medicaid Plans—Created to Streamline Care for Dually Eligible Individuals—Failed to Increase Medicaid Participation in High-Poverty Communities