Brief

Contributors to Post-injury Mental Health in Urban Black Men with Serious Injuries

A life course view

JAMA Surgery – published online June 5, 2019

Key Findings

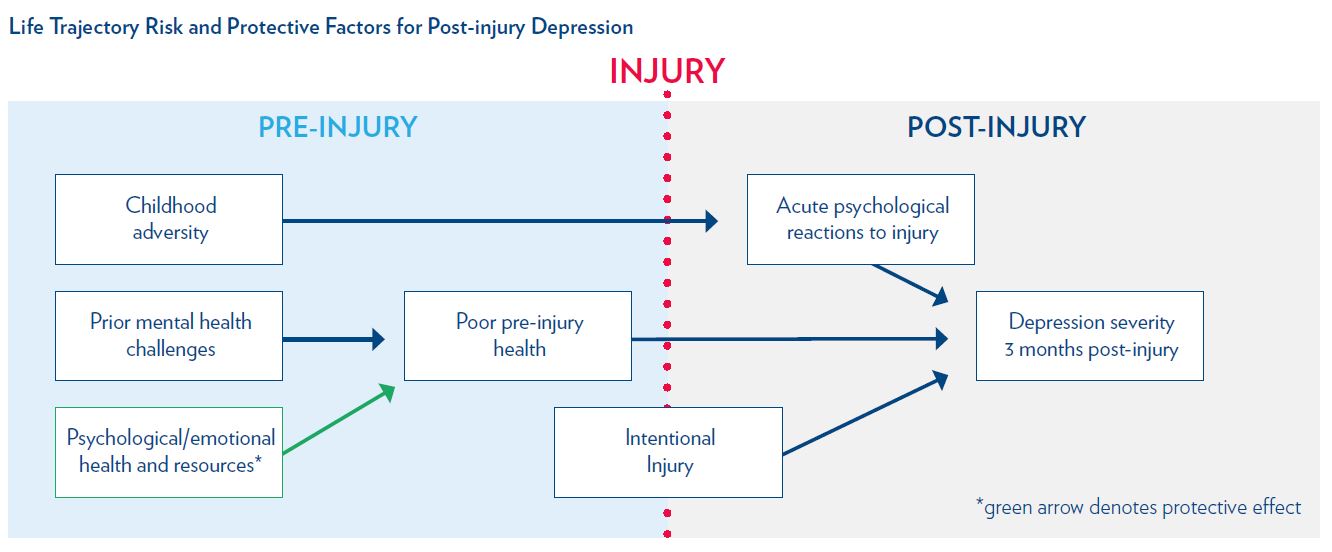

Factors over the life course affect the mental health of urban black men with serious injuries. Childhood adversity, pre-injury physical and mental health conditions, and intentional injury (violence) are risk factors for post-injury depression and posttraumatic stress. Clinicians should expand assessment beyond the acute injury event to identify those patients at risk for poor mental health outcomes.

The Question

Although injury is a short-term event, it can lead to long-term mental health problems, with up to 50% of patients experiencing post-injury depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Injured black men are particularly vulnerable because they have high exposure to stressors, are more likely to be injured than white men, and are more likely to have undiagnosed psychological consequences than white men. Sending these men back to the community with unrecognized mental health problems contributes to suboptimal recovery, and can lead to repeated injuries, self-medication for symptoms, or interactions with the criminal justice system.

Urban black men from disadvantaged neighborhoods are exposed to racism, poverty, and other traumas throughout their lives, which may contribute to the severity of mental health conditions after injury. In this study, the authors use statistical modeling to understand the factors from childhood and adulthood that contribute to depression and PTSD severity in black men with serious injuries.

The Findings

The final sample included 500 black men, over half (55.5%) of whom had intentional injuries due to interpersonal violence. Almost half (45%) met diagnostic criteria for either depression or PTSD three months post-injury: 65 (13%) were positive for depression, 51 (10.2%) were positive for PTSD, and 111 (22.2%) were positive for both outcomes.

The flow chart below shows the risk and protective factors across the life trajectory that influence depression severity post-injury. Childhood adversity was associated with acute psychological reactions to injury (e.g., immediate emotional reactions, physical reactions, and subjective appraisal of life threat). A history of prior mental health challenges influenced poor pre-injury health, while psychological/emotional health and resources (e.g., self-efficacy and hope) protected against poor pre-injury health. In turn, acute psychological reactions to injury, poor pre-injury health, and intentional injury, were each associated with depression severity. The model for PTSD symptom severity showed similar results.

The Implications

The intersection of prior trauma and adversity, exposure to challenging disadvantage, and poor pre-injury health should not be overlooked in acute injury care. These findings support the importance of trauma-informed care for injury patients, especially black men, who as a group have disproportionately high rates of childhood adversity.

The current findings have clinical importance since, in a national survey of trauma centers, only 7% of centers incorporated routine screening for PTSD symptoms. Because symptoms develop after hospital discharge, further development and use of screening tools designed to assess post-injury mental health problems is warranted. Collaborative services that integrate trauma and mental health care and cross phases of care (from acute to community care) are also needed. The findings of this study identify characteristics and exposures of injured black men at higher risk for poor mental health outcomes, factors that can be obtained from a focused history and that can help target services to those with highest need.

The Study

The study used a prospective, cohort design in which men were enrolled during acute hospitalization at an urban, level 1 trauma center in Philadelphia, and followed up with three months post-discharge. Men with injuries who were hospitalized, self-identified as black, were 18 years or older, and resided in the Philadelphia region were eligible. Those experiencing a cognitive dysfunction or psychotic disorder, hospitalized because of attempted suicide, or receiving treatment for depression or PTSD were excluded. The data were collected from January 2013 to October 2017.

Recruitment, written informed consent, and baseline interviews were conducted in the hospital when the participant was medically stable. Demographic and injury-associated information were obtained via self-report and from the medical record, while self-reports of acute stress responses and risk and protective factors were collected during interviews. Interviews to assess PTSD and depressive symptoms were conducted three months after hospital discharge, primarily in the participant’s home.

Lead Author

Therese S. Richmond, PhD, FAAN, CRNP is the Andrea B. Laporte Professor of Nursing and the Associate Dean for Research & Innovation at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Nursing. Dr. Richmond’s research focuses on improving recovery from serious injury by addressing the interaction between physical injury and its psychological repercussions, particularly in vulnerable populations. Two decades ago she co-founded what is now the Penn Injury Science Center, an interdisciplinary center that conducts research and translates scientific discoveries into practice and policy with the greatest potential to prevent injury and violence and improve outcomes.

Her co-authors are Douglas J. Wiebe, PhD, Patrick M. Reilly, MD, and Justine Shults, PhD, all of the University of Pennsylvania; John Rich, MD, MPH, of Drexel University; and Nancy Kassam-Adams, PhD, of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. This research was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health (grant R01NR013503).