Health Care Access & Coverage

News

COVID-19 Boosts Deployment of Technology-Enabled Remote Health Care Delivery Systems

Penn Medicine Innovation Managers Detail Dramatic Changes at LDI Virtual Seminar

Along with the health catastrophe and economic collapse it has wreaked across American society, COVID-19 has also turned out to be a boon for a number of promising new health care delivery concepts whose implementation was previously impeded by often-inflexible government regulations and rigid reimbursement rules. That was the central message of the seventh “Experts at Home” virtual seminar convened by the University of Pennsylvania’s Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics (LDI) to explore pandemic-related health care issues.

“The pandemic has made it necessary to innovate in the way we deliver care.” said LDI Executive Director Rachel Werner, MD, PhD. “In some ways, it’s the best of times for those of us interested in rethinking and transforming the American health care system.” She was moderator of the May 22 seminar entitled Health Care Innovation During COVID-19.

Four health innovation experts

Taking part in the discussions were four top experts charged with developing and managing transformative new health delivery systems throughout the University of Pennsylvania Health System (UPHS). All are LDI Senior Fellows connected to the eight-year-old Penn Medicine Center for Health Care Innovation (CHCI), one of the first clinically-oriented health services research centers embedded within a large health system.

“From the 30,000-foot level, I think everyone is marveling at how fast institutions have changed in response to COVID,” said panelist David Asch, MD, MBA, CHCI Executive Director. “It shows that innovation really is possible in health care and, in fact, it can happen much more quickly than a lot of people worried about in the past.”

Asch heads a network of research teams that have been working for years to develop, test and implement new evidence-based systems delivering “technology-enabled care” remotely in places far beyond the traditional brick-and-mortar boundaries of hospitals and clinics. These systems connect patient and hospital/clinician via text message, email, online video and phone at the same time they often monitor a patient’s condition and progress over extended periods of time. Among the individual Penn Medicine systems currently up and running are COVID Watch, Heart Safe Motherhood, Healing at Home, Pregnancy Watch, Penn Med With You, and Penn Medicine OnDemand.

A Penn digital utility

Except for OnDemand, the systems are driven by an artificial intelligence engine within the Penn Medicine-created computer communications utility called the Way to Health platform. It connects to patients out the front end. Out the back end it connects to a network of human clinicians. In the middle is an automated triage system that begins with patient self-service and uses exception management principles to escalate care responses to various levels.

The power of such a system is that it can deal with hundreds or even thousands of patients simultaneously, monitoring their input, responding to clinically relevant changes, and triggering appropriate kinds of care responses. The systems are particularly well suited for managing the sudden spikes of enormous patient demand and anxiety generated by something like the coronavirus epidemic.

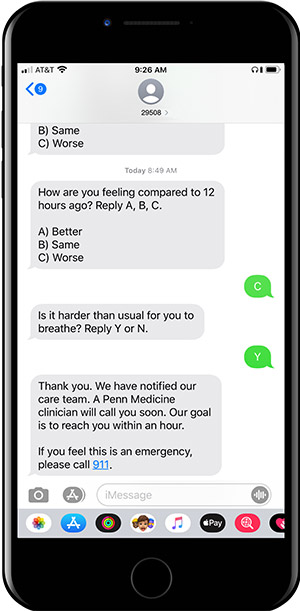

Ongoing clinical connection

For example, COVID Watch uses text messaging, sending infected patients twice-a-day messages asking questions like “How are you feeling compared to 12 hours ago?” or “Is it harder than usual for you to breathe?” The patients’ responses determine if they need to continue doing what they’re doing at home; require a call-back and further consultation with a nurse; or need to come into the emergency department for further evaluation and treatment. The daily monitoring of their condition goes on for weeks until their viral infection is resolved.

“We could see that automation alone was not going to work,” Asch said of the COVID Watch system that has enrolled 3,800 patients in the last two months. “All those silly COVID trackers and apps that you see online are really pretty meaningless because at the end, most of them say something like ‘contact your doctor’ — they take you back to square one. With COVID Watch, the goal was an automated system paired with a 24/7 clinical backend of real humans. So patients could be automatically connected to a nurse or doctor who could reach out to them in an average of about 10 minutes. It’s really quite amazing.” Only about 20% of patients have required a nurse or physician to call them, Asch said. The other 80% were watched over and cared for by the automated system.

Telemedicine

The Innovation Center began exploring use of the more technologically sophisticated telemedicine video systems six years ago; three years ago, the project was moved into Penn Medicine’s Center for Connected Care and renamed Penn Medicine OnDemand Virtual Care. Seminar panelist Krisda Chaiyachati, MD, MPH, MSHP is its Medical Director.

While the use of telemedicine systems was constrained by insurance reimbursement rules and other barriers, Penn Medicine began more extensive telemedicine testing by using the system to provide medical care for its own employees. In January, after reaching an agreement with Independence Blue Cross, Penn Medicine OnDemand began moving toward wider use within UPHS’ general population of patients.

“Then it was March and COVID hit,” said Chaiyachati, “and we were suddenly in incredible demand. Before, we were doing 50-60 telemedicine visits a day. Within a week that went to 250-300 visits a day, and there was one day we would have needed to have seen nearly 500 patients just to meet demand.”

Since then, Penn Medicine OnDemand has gone fully mainstream for the health system. More than 150 physicians or nurse practitioners have been trained along with nearly 100 nurses to help support OnDemand over the past three months.

“Simultaneously, outside of OnDemand, our primary care network and ambulatory network got better at doing telemedicine across the entire network,” Chaiyachati said, “and that has now gone from 300 appointments a week to 40,000 a week across the whole system.”

“I think what we’re seeing during this COVID period is an analogy of what the future will hold for primary care,” he continued. “We really need to think about how we can efficiently position all the critical skills that we have — nurses, medical assistants, front desks. How can they all be a part of an interwoven network that leverages telemedicine to take care of a whole range of conditions and get patients moving in and out of those different tiers of need?”

OB-GYN

In the Obstetrics and Gynecology Department, COVID raises different problems and issues because, said panelist and Director of Obstetrical Services at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Sindhu Srinivas, MD, MSCE, “pregnancy care is not elective and we can’t postpone it to six months later.”

At the same time, the department has to deal with both patients’ potential fears of infection and inclinations to not come to office visits for procedures that could only be done there.

Prior to the pandemic, Srinivas and her team worked with the Innovation Center to create the Heart Safe Motherhood system for post-delivery monitoring of new mothers’ blood pressure, and a second text-messaging monitoring program called Healing at Home.

“One of our primary challenges was figuring out how we safely balance in-person care, like ultra sounds, versus things that can be postponed or have an altered schedule,” Srinivas said. “We had already been working on these innovative models, so it was easy for us to ramp up an adaptation for the pandemic because we already had the culture and were primed for this.” “This” was the creation of Pregnancy Watch, based essentially on a clone of the COVID Watch system.

“We were able to scale up pretty quickly and very safely monitor lots of pregnant women and escalate when it’s needed — it’s been about 15-20% of women that need to be escalated,” said Srinivas.

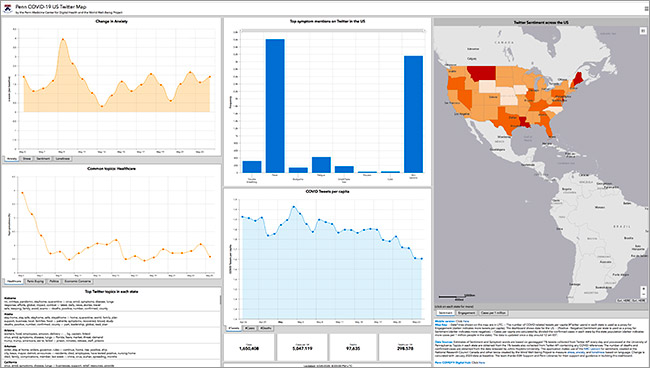

Digital health research

Panelist Raina Merchant, MD, MS, the Director of the Penn Medicine Center for Digital Health, has worked with her team for years to perfect methods for extracting health information from social media streams. Shortly after the pandemic hit, her center launched Penn COVID-19 US Twitter Map, that tracks and charts daily trends in pandemic-related anxiety, stress, loneliness and other topics.

It took Merchant’s center about two weeks to also create Penn Medicine With You, which is both a website and a text-messaging service aimed at vulnerable populations and populations sheltering in place.

“While people are worried about their health and safety, they’re also worried about a multitude of other things, and they’re looking for trusted information,” said Merchant. “Penn Medicine With You provides information about things like where to find free lunches for kids or places for online education. The idea is to share information about resources that are hyperlocal and provide information about other things that impact health in the era of COVID.”

Remote care delivery disparities

A serious concern for the panelists was the potential of the “digital divide” to increase remote care delivery disparities for vulnerable populations in low-income communities as the use of technology-enabled remote care systems expanded.

“We’re all cognizant of that potential,” said panelist Srinivas. “That’s why it’s important to assess your patients’ and your community’s ability to use different types of technologies. That was a major element in the success of our Heart Safe Motherhood program. We found almost 95% of our patients have a smartphone and were able to receive and send text messages. Before we implemented the program, we did have significant disparities. Afterwards, our randomized trial found Heart Safe Motherhood had eliminated disparities. All the women in all communities were able to equally send us blood pressures and we were able to act on them and keep those patients safe.”

Chaiyachati agreed. “If we’re beholding to constantly thinking about video-based telemedicine, I think we’re stuck and we’re actually going to create a disparity challenge because we haven’t thought about all the other ways lower income communities, rural communities, and other vulnerable populations might be communicating, and how they might prefer that method for connecting with clinicians. The COVID Watch program is an example of that. Its text-message methods draw a higher proportion of African Americans and Latinos compared to what we usually see in our general population. So, we’re actually seeing more of these populations using that tech-based program than I think we would have otherwise.”

A second serious concern was whether or not the changes that have enabled the innovative use of these new remote care delivery systems will be retained and embraced by regulators and insurers when the COVID crisis is over.

“The impact of COVID is not going to last three months,” said panelist Merchant. “It’s not going to last six months. It will be with us, along with these new ways of doing things, for quite a while. I think we’re going to be seeing the impact of these new systems on vulnerable communities and chronic-condition care for a very long time because their value is becoming so clear.”