Health Equity

News

COVID-19’s Disproportionate Damage in African American Communities

Penn LDI/BU Population Health Research Workshop Eyes Short- and Long-Term Racial Inequities

The spread of COVID-19 infection and death throughout the African American community is so extensive, it’s erasing the hard-won gains made in the Black life expectancy rate since 2005, keynote speaker Trevon Logan, PhD, told the LDI/Boston University Fifth Annual Population Health Science Research Workshop.

That was just one of several long-term health and socioeconomic dimensions of pandemic impact Logan unpacked in his presentation, “The Shadow of the Past: Black Americans and COVID-19,” broadcast from the University of Pennsylvania on December 11.

“Dr. Logan’s synthesis of the disproportionate burden borne by Black Americans during the COVID-19 pandemic was incredibly powerful because it took data we’ve all seen and tied to the deep history of structural racism,” said Atheendar Venkataramani, MD, PhD, LDI Senior Fellow, moderator, and one of the three founders of the Population Health Science Research Workshop. “Drawing from a number of disciplines, his talk illuminated how the COVID-19 crisis was not just due to recent policy failures, but also due to our failure to definitely address structural racism throughout our history.”

Established five years ago by three researchers from Penn, Boston University and the University of Houston, the Population Health Science Research Workshop is designed to bring together different academic disciplines around causal questions related to population health. In virtual form, this year’s gathering focused on two topics: how COVID-19 exacerbated long-existing racial and ethnic inequities, and the call for racial justice following George Floyd’s killing. The event included presenters from 17 universities, the World Bank and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

Logan’s keynote

“My remarks will review the COVID-19 we know right now from a few dimensions and think about what that really tells us about American society,” said Logan, a Hazel C. Youngberg Distinguished Professor of Economics at Ohio State University, Research Associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), and Director of NBER’s Race and Stratification in the Economy Workshop. His research specializes in economic history, economic demography, and applied microeconomics.

Since the coronavirus outbreak in March, African Americans have accounted for the highest death rates in states across the country. In many states, their share of COVID deaths is double their share of the population.

“The unadjusted mortality risk specifically for black people is still twice that for whites,” said Logan. “So, adjusted or unadjusted for population, this is a highly racially disproportionate pandemic, that is, with incredible precision, targeting black people in terms of its disproportionality in mortality. This is shocking to me in many different ways.”

Leading cause of death

“For context, think about the fact that this is an entirely new cause of death; in December of 2019 it didn’t appear on any death list, and now it is the third leading cause of death among Blacks and it is changing the life expectancy at birth rate,” said Logan.

He explained that in 1900, the difference in life expectancy at birth between Blacks and whites was ten years. In 2005 — more than a century later — that gap for Blacks had closed to five years. But COVID-19 is now reducing life expectancy predictions for whites by one year and for Blacks by two years, with further declines likely as the pandemic continues.

Other dimensions of racially disproportionate impact that Logan discussed included:

Economics and Wealth Gap

Beyond the pathogenic and mortality effects, the pandemic is having a disproportionate economic impact on Black communities that were already in a weaker economic position. The median income of black households in 2019 was 39% lower than that of white households. Black families have fewer resources to weather a crisis and are being hit harder by unemployment.

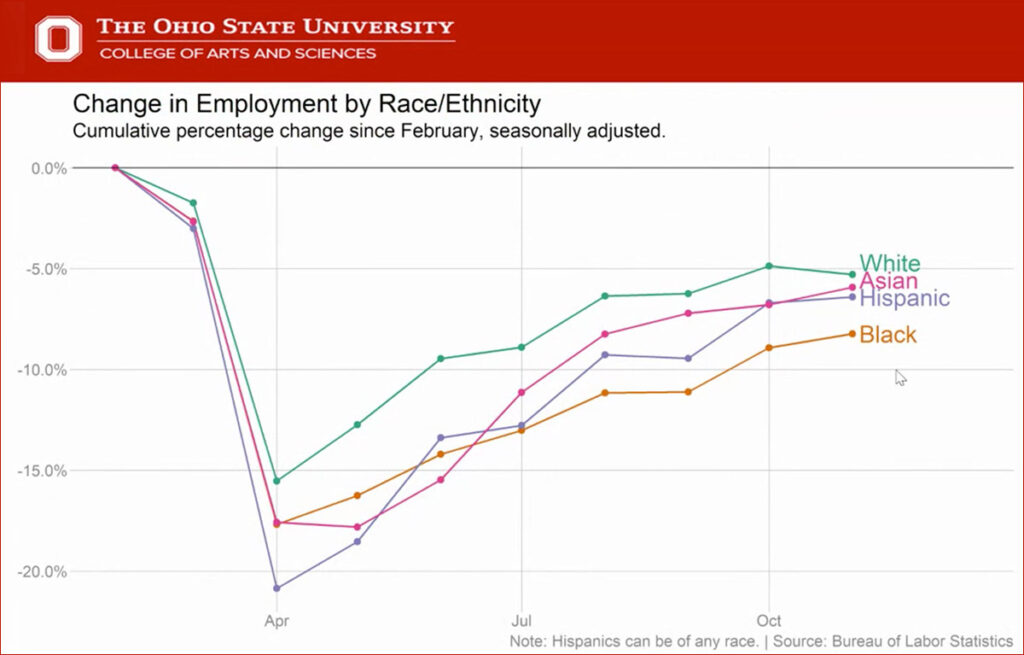

“The impact of the initial decline in employment was not racially distinct,” said Logan. “The recovery, however, has shown significant racial disproportionality. Black employment recovery is slower than any other racial group.” He also cited a 2020 Howard University study that found Black people often wait an additional week longer than whites to receive unemployment benefits after filing for them.

He pointed to a Pew Research Center survey that found 48% of Blacks said they could not pay all their household bills; 26% of whites reported the same problem. Twenty-five percent of black renters are behind in their rent payments. In September, more than 10% of Black homeowners were behind in their mortgage payments — the highest rate for any group.

“Blacks do not have the ability to fall back on wealth to support themselves as they go through this pandemic,” Logan said. “This is something we don’t talk about in light of the pandemic. In the third quarter of 2020, $100 billion was extracted from home equity in the U.S. This is how households with wealth get through this economic catastrophe. Those who have access to some form of wealth are able to use it and turn it into liquid assets to weather this sort of storm. Blacks do not have this ability.”

Food Insecurity

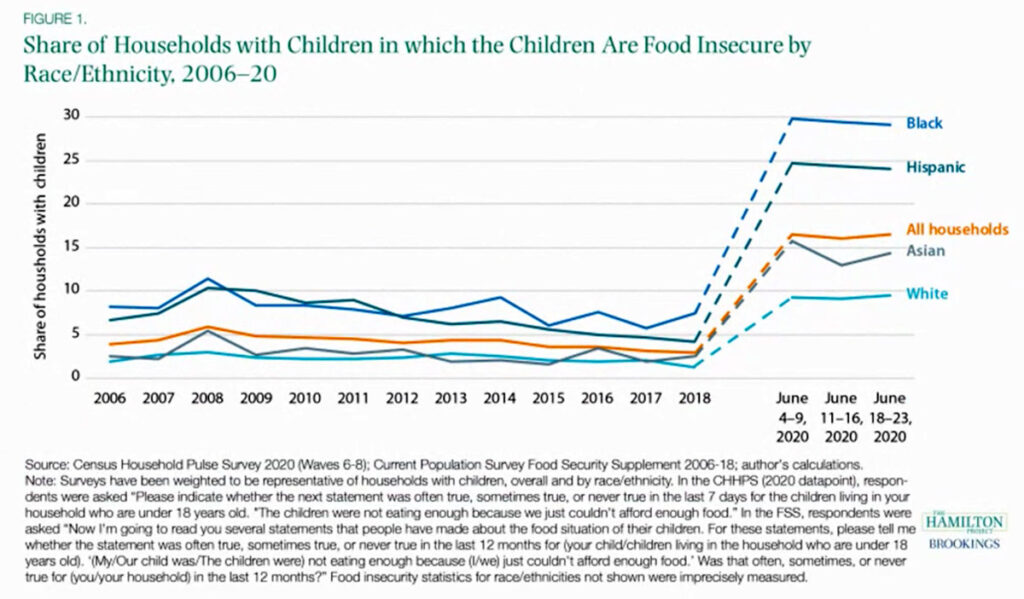

A June survey found that nearly 30% of Black households with children reported being food insecure. In comparison, only a little over two percent of white households with children reported food insecurity.

“Over the course of this summer, we saw a significant acceleration in the share of households with children who were food insecure and Black households were topping out,” said Logan. “By November this had declined somewhat as 23% of Black households with children reported food insecurities. That is still high above trends and has serious consequences.” Logan’s chart also showed that 16% of adults in households with children reported they sometimes hadn’t had enough to eat during the past week.

Stress and Mental Health

“We know that 71% of Blacks know someone who has been hospitalized or has died from coronavirus,” Logan said. “This is much higher than any other group and is leading to alternative realities in how people are experiencing the pandemic. The way we have responded, in terms of public health, has taken away many of our social interactions. We are missing rituals of grief and community when people do succumb to the virus. This is not something we can take lightly because it implies that the psychological toll of the virus is also disproportionate.”

“All of these things have significant impact on stress and I worry deeply about the non-COVID health of black people in particular in light of the economic crisis,” said Logan. “The impact of this type of stress on hypertension, inflammation, and psychological health is important. We must have a serious national discussion of mental policy. We cannot think that magically, with the dissemination of a vaccine, we are going to turn the lights on and go back to normal.”

Vaccine Hesitancy and Tuskegee

Citing the latest statistics that 42% of Blacks don’t intend to get the COVID-19 vaccine, Logan spent the end of his presentation discussing the historical roots of their mistrust of the U.S. medical system.

“When we talk about this lower rate of blacks taking up the vaccine, we talk a lot about the Tuskegee experiment,” Logan said. “We need to unpack this and think about why we go to Tuskegee continuously as a way of thinking about racial disparities and medical mistrust. The first thing we need to do is to put Tuskegee in its place.”

The skepticism about a vaccine is deeply related to the fact that black people believe fundamentally that the entire response to this disease is a function of the fact that it has disproportionately affected black communities.

Trevon Logan

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study, was a U.S. Public Health Service clinical experiment involving African-American sharecroppers in Macon County, Alabama. The goal was to study the course of untreated syphilis among 600 men who believed they were receiving a form of medical care. The project ran from 1930 to 1972, when an Associated Press exposé shut it down. Now referred to by historians as “arguably the most infamous biomedical research study in U.S. history,” the project resulted in sweeping changes in the ethical standards and rules governing human subject research.

“Tuskegee is in a classic southern “Black Belt” county and a place of intense economic distress,” said Logan. “Its people are poor and highly likely to remain poor. If we’re picking a part of the country that is economically distressed, with low levels of investment in public goods and high rates of disease prevalence, this would be it.”

Historical Lynchings

“It’s important to understand the political economy of places like this where African Americans are a sizable portion of the population but are not politically included in policy. Blacks wait longer in terms of time to vote. These counties have, on average, lower rates of voter participation as a function of the rate and number of lynchings that took place in them before the Voting Rights Act, 1965. And Macon County, Alabama, is one of these places that had historical lynchings.”

“The first thing to understand about the Tuskegee experiment is that it was something that targeted the vulnerable. This isn’t just a story of racial inequality; it is literally a story of exploiting a vulnerable population. The experiment was also woven in with economic, social and political inequality that was a critical component — and also depended upon the medical establishment, both black and white.”

“Even without Tuskegee, however, there would be a variety of contemporary factors that will be related to medical mistrust: the function of the medical system, the continued bias in medical care, racist ideas about black people, and generalized racial treatment,” said Logan. “These cannot be ignored. We have to remember that for many black people, the medical establishment is also a function of the state. So, to ask black people to be particularly trustworthy of the medical establishment, which is part of the state, is asking them to be cognitively dissonant.”

Policy today

“If we think about what’s happening in terms of policy today,” Logan continued, “it is not as if African Americans have a lot of policy options when we have a political party that is captive to one voice and, as of 2020, is offering not a single policy platform.”

“How can a state that refuses to prosecute and root out its violent impulses against black people now tell them to do something they believe is in their best interest and expect African-Americans to believe that?,” Logan asked. “It doesn’t make a great deal of sense. The skepticism about a vaccine is deeply related to the fact that black people believe fundamentally that the entire response to this disease is a function of the fact that it has disproportionately affected black communities.”

“There’s no way of getting around the commingling of the way virus is rooted in our own racialized inequality, and then expect us to be completely divorced of race as we work towards a solution,” Logan concluded.