Health Care Access & Coverage

Brief

Expanding Scope of Practice After COVID-19

Conference Summary

To expand access to health care during the COVID-19 pandemic, many states relaxed or waived regulations that define the scope of health professional practice. This experience highlights the need to ensure that all health care professionals practice to the full extent of their capabilities—an issue that predates and will outlast the pandemic. In a virtual conference on November 20, 2020, Penn LDI and Penn Nursing brought together experts in law, economics, nursing, medicine, and dentistry to discuss current gaps in health professional scope of practice, what we have learned from COVID-19, and how to rethink scope of practice to better meet community and public health needs.

Introduction

In each state, scope of practice (SOP) regulations primarily define the services a health professional is legally allowed to perform. The pandemic has highlighted how these regulations affect public health, equity, and patient care. In response to emergency needs, some states have modified their regulations, with questions now arising about whether to make the changes permanent. To set the stage for the conference discussions, Penn Nursing Dean Antonia Villarruel, PhD, RN pointed out four key considerations in SOP reform:

- Health professional practice is constantly changing and innovating due to changes in supply, technology, and demands for care. Retail clinics and telehealth are just two examples of recent changes in health care delivery. State regulation must evolve to meet the needs of these changes in practice and policy.

- The scope of health professional activities could and should overlap. While different health professional groups have unique capabilities and functions, many activities can cross professions.

For example, should a dentist, dental hygienist, or veterinarian provide a flu shot? Should a home care nurse or physical therapist order durable medical equipment for a patient at home? Should a hospice nurse legally declare someone dead? Should a pharmacist manage some aspects of chronic illness?

- We should assume and promote collaboration between health care providers, rather than oversight of one profession over another. Competent providers will refer to others to manage issues that require different expertise; the fundamental question is whether a proposed service can be provided safely and effectively, given a professional’s education and training.

- We should transcend “turf” battles and payment issues and focus instead on access, safety, and equity. Debates about state regulation should center around the patient and the public’s health, rather than on competition and reimbursement issues between health care professions.

Economics of Professional Regulation

Protect Consumers, Not Competitors

In a keynote address, Martin Gaynor, PhD, gave a broad overview of economic implications of SOP regulations and their intended consequences. He noted that the proper role of these regulations was to protect consumers, not to impede competition. When health or safety concerns warrant certain restrictions on practice, they should be based on evidence and narrowly tailored. He offered his vision of the outcomes of appropriate SOP regulations:

- They expand choice and foster competition, allowing consumers to decide among qualified providers. In theory, increasing competition could lower prices.

- They expand the supply of providers and enhance their productivity, by promoting increased efficiency and specialization to the “top” of their capabilities. Even before the pandemic, updating SOP regulations were part and parcel of health care reform efforts to increase supply to meet the increased demand for services.

- Pandemic-related emergency relaxation in state SOP laws may help rationalize state regulation by producing evidence of success. If there is evidence of success, the changes should be retained.

State SOP Responses to COVID-19

Sydne Enlund of the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) provided an update on how states have responded to the health care needs of the pandemic by temporarily amending their SOP regulations. The NCSL is currently tracking more than 80 changes enacted that affect the health care workforce. Most of the SOP changes have been by executive order of the governor, and last only through the duration of the declared emergency.

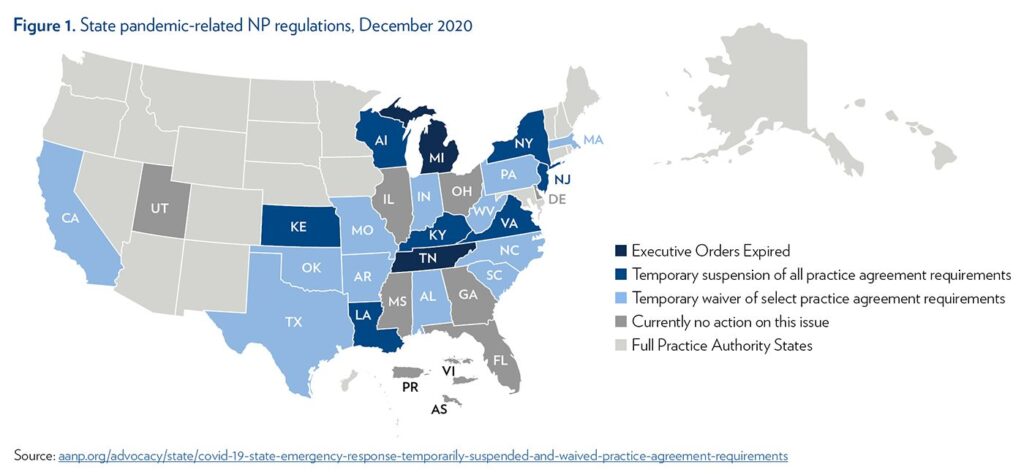

- Many states have waived or suspended supervisory or collaborative agreement mandates for nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs). Some of these changes have allowed NPs and PAs to practice remotely without a physician present, and to practice in all settings of care, while others have increased the number of NPs and PAs a physician can supervise. Figure 1 summarizes these changes for NPs as of December 2020.

- Prior to the pandemic, states were examining SOP for a variety of oral health providers, including dental therapists and dental hygienists. Currently, 13 states license dental therapists to perform services such as taking X-rays, providing sealants and topical fluorides, and routine dental screenings and assessments. In response to the pandemic, states have changed SOP by allowing some oral health providers to practice outside of the dental office with or without the supervision of a dentist, expanding the types of permissible procedures, and granting limited prescriptive authority.

- Pharmacists are trained to dispense prescription medications and counsel patients, and in some states, they can also conduct health and wellness screenings, provide some immunizations, oversee the ordering of medications, and provide advice on healthy lifestyles. In anticipation of a COVID-19 vaccine and the need for widespread distribution, the federal Department of Health and Human Services issued guidance in September 2020, allowing all pharmacists to administer a COVID-19 vaccine. Some states have expanded pharmacist SOP to order and administer coronavirus tests as well.

Access, Equity Gaps in SOP Regulation

Moderated by Matthew McHugh, PhD, JD, MPH, RN, a panel of practitioners and researchers discussed current gaps in SOP regulation and the implications for providers and patients. In general, patients want access to quality health care services, which they value more than the nuances of provider SOP arrangements.

Margo Brooks Carthon, PhD, RN, framed the discussion of NP SOP as an issue of equity. She noted that NPs bring specific skills, knowledge, and expertise to many underserved communities.1

- States with overly restrictive NP regulations have less access to primary care, longer waits, and lower supply of providers in historically marginalized communities and underserved populations. Because NPs are more likely to practice in these areas, restrictive SOP regulations constrain a valuable resource in improving access to health care.

- There is strong evidence of the benefits of expanded NP practice in the 22 states that allow them full practice authority and in the Veterans Health Administration, where NPs practice to the full extent of their capabilities across the country.

- Given how many states have suspended restrictions during the pandemic, it is clear that regulators act in the public interest when the health of the nation is at risk. The question is, do they have the same determination to change SOP regulations for these underserved communities?

Jim Carney, PA, noted that SOP problems for PAs stem not so much what they are allowed to do, but how they are required to do it. In general, SOP regulations impose frictions within the system that add costs and administrative burden without known benefits.

- Many states tether a PA license to a specific physician or specify the maximum physical distance between a PA and physician. These kinds of provisions restrict PA mobility and have become even more troublesome as telehealth becomes more widespread.

- SOP regulations often set maximum PA-to-physician ratios. These arbitrary limits may stifle the creativity needed to deliver innovative care, especially in inpatient settings and rural areas.

- Practice agreements often specify the drugs that can be prescribed, and subsequently need to be officially amended to respond to changes in medication use and practice. The paperwork burden means that PAs can be out of compliance as medical practice evolves.

It is clear that regulators act in the public interest when the health of the nation is at risk. The question is, do they have the same determination to change SOP regulations for underserved communities?

Donald L. Chi, DDS, PhD, commented on known problems with access to dental care, and how dental therapists can alleviate the maldistribution of dentists.

- Dental therapists are not new, as they were first licensed in Alaska in 2005. They are well trained to provide a limited set of services, including exams, fillings, X-rays, and simple extractions.

- They practice under general supervision of dentists, who do not have to be co-located. While organized dentistry has opposed dental therapists, many practicing dentists are supportive of the role.

- Evidence from 10 years of experience in Alaska shows that dental therapists have made a positive difference, for both children and adults, with the same quality of care as dentists.2 Improved outcomes include more preventive care, fewer teeth removed, and fewer dental emergency visits.

Bianca Frogner, PhD, noted that recent studies support the call for modernizing SOP regulations for a variety of non-physician providers.3 In some cases, reimbursement decisions restrict practice even where regulators have not, creating inefficiencies within and across states.

- The evidence is strong that expanding SOP for NPs improves access to primary care, particularly in rural areas, with similar evidence for PAs; and that dental therapists have increased access to the services they are trained to deliver.

- Pharmacists have advanced training to provide clinical care, but reimbursement restrictions prevent them from providing many services. Overcoming this barrier would provide an opportunity to improve patient education.

- For physical therapists, all states allow direct access, but often insurers require a physician referral. In these cases, insurers are following different codes of conduct from the state regulators. Evidence shows that going to physical therapy first reduces the risk of subsequent opioid use.4

Updating SOP Regulation, and Potential Roadblocks

Moderated by Allison Hoffman, JD, a second panel discussed how SOP regulation can promote a health care workforce that better matches the needs of the population, and some of the barriers to SOP reform.

Edward Timmons, PhD, noted that there is overwhelming evidence from 22 states that the benefits of full practice authority for NPs far outweighs the cost, and is in the best interest of patients and taxpayers.

- Evidence is just emerging about the temporary COVID waivers to expand SOP; one recent study in the Midwest found that states with waivers were able to reduce death rates from COVID-19.5

- Regulatory decisions need to focus less on the large amount of training that physicians receive, and more on the outcomes of care. The substantive question is whether other health professionals (NPs and PAs) can provide high-quality care, and the evidence is clear that they do. These health professionals are a critical resource, especially where few physicians are available.

- The barriers to changing the status quo are political, rather than substantive. Additional research is not sufficient to eliminate barriers to SOP reform. Sometimes the interests of the few outweigh benefits to the many; lobbying to maintain the status quo may block any SOP reform. One way to overcome this is to organize professionals and consumers to put pressure on legislators.

William Sage, MD, JD, explained how the use of antitrust law can be used to overcome political forces that maintain the status quo.

- Political settlements are embedded in SOP regulations. Antitrust actions do not reverse unwarranted restrictions, but they alter the politics and can result in new political settlements.

- For example, a Supreme Court decision found that the North Carolina Board of Dental Examiners had engaged in anti- competitive behavior by preventing non-dentists from providing teeth-whitening services. The decision meant that licensing boards were subject to antitrust regulation, and subsequently, the politics changed: boards could no longer implement wide restrictions without considering their anti-competitive nature.

- The time is ripe for regulatory reform, as SOP and telehealth are closely linked. The pandemic-related changes also provide an opportunity to alter the presumption that SOP cannot be expanded without extensive evidence of safety. Given the COVID waivers, however, the presumption should be that regulatory changes should remain unless there is evidence of harm.

Penny Kaye Jensen, DNP, APRN, discussed lessons from the VA’s 10- year battle to implement full practice authority for NPs in the nation’s largest health system, which serves 9 million veterans.

- The VA wanted to standardize practices across states, to use resources efficiently, and to reduce long waiting lists for primary care. To implement full practice authority across states, they invoked the federal ability to supersede state regulation.

- Proposed reforms encountered pushback from political action committees, and it took a year to write congressional legislation. On the Hill, advocates had to correct the misperception that full practice authority meant that NPs would no longer consult with physicians or that NPs would provide services beyond their training and capabilities.

- The effort also provoked resistance from VA physicians, who thought that they might be replaced by NPs as less costly providers. By most accounts, however, full practice authority has alleviated stress on the primary care physician workforce, rather than replacing the workforce.

Ying Xue, PhD, RN, discussed recent work on the actual and potential effects of expanded SOP on access to primary care for vulnerable groups.

- The sheer numbers of the NP workforce (more than 200,000 practice in primary care) have huge potential to boost primary care access, especially given the increasing trend for team care among NPs, PAs, and physicians.

- A recent study shows that the primary care NP workforce is well distributed and growing in low-income and rural areas. This counterbalances the maldistribution of the physician supply in these areas.6

- Full practice authority for NPs is associated with greater supply of NPs and more use of NPs as primary care providers and for primary care visits. This boosts primary care capacity in areas that need it the most.

- Regulators should consider the pivotal role that NPs play in in delivering primary care to vulnerable populations, and how to incentivize caring for these populations.

Coalitions of stakeholders, including health care providers and consumer organizations such as the AARP, are needed to ensure that the public’s voice is heard.

Conclusion

Julie Fairman, PhD, RN, provided historical context for SOP regulation, presented some themes from the day’s discussions, and offered some concluding remarks.

- In the early 20th century, the drive toward more science-based medical curriculums also became the basis for licensure and SOP standards that used the length and complexity of clinical training as a proxy for patient safety. But this occurred without evidence that the growing content or length of the clinical practicum made a difference in the quality or safety of patient care. SOP regulations became increasingly broad, exclusionary, and focused on physician skills and knowledge.

- The consequences of present SOP restrictions include lack of necessary providers, decreased access to care, poor health outcomes, and increased cost. Too many geographic areas are subject to primary care workforce shortages, which inhibit both price and non-price competition between health care providers. Market forces may be slow to clear these shortages, in part, due to regulatory impediments to competition.

- State policymakers should account for competitive costs when considering SOP restrictions and carefully examine the countervailing health and safety benefits that may or may not be associated with each policy. Several speakers also noted that the advantages of regulatory consistency across states, as the example of the VA shows us.

- In rethinking SOP restrictions, regulators should center their decisions around the patient and the public. Regulatory bodies are ultimately responsible to the public, and the public’s voice needs to be heard in the debate. Coalitions of stakeholders, including health care providers and consumer organizations such as the AARP, are needed to ensure that the public’s voice is heard.

References

- Poghosyan, L., & Carthon, J.B. (2017). The Untapped Potential of the Nurse Practitioner Workforce in Reducing Health Disparities. Policy, Politics, and Nursing Practice, 18(2):84-94.

- Chi, D.L., Lenaker, D., Mancl, L., Dunbar, M., & Babb, M. (2018). Dental Therapists Linked to Improved Dental Outcomes for Alaska Native Communities in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta. Journal of Public Health Dentistry, 78: 175-182.

- Frogner, B.K., Fraher, E.P., Spetz, J.S., Pittman, P., Moore, J., Beck, A.J., Armstrong, D., & Buerhaus, P.I. (2020). Modernizing Scope-of-Practice Regulations — Time to Prioritize Patients. New England Journal of Medicine, 382:591-593.

- Sun, E., Moshfegh, J., Rishel, C.A., Cook, C.E., Goode, A.P., & George, S.Z. (2018). Association of Early Physical Therapy With Long-term Opioid Use Among Opioid-Naive Patients With Musculoskeletal Pain. JAMA Network Open, 1(8):e185909.

- Chung, B.W. (2020). The Impact of Relaxing Nurse Practitioner Licensing to Reduce COVID Mortality: Evidence from the Midwest. Illinois Labor and Employment Relations. Retrieved from http://publish.illinois.edu/projectformiddleclassrenewal/files/2020/06/The-Impact-of-RelaxingNurse-Practioner-Licensing8413.pdf

- Xue, Y., Smith, J.A., & Spetz, J. (2019). Primary Care Nurse Practitioners and Physicians in Low Income and Rural Areas, 2010-2016. JAMA, 321(1):102–105.