One Agency’s Maps Are Known For Documenting Redlining

But Many Other Factors Played a Role in Denying Loans, LDI Fellow Says

Population Health

Blog Post

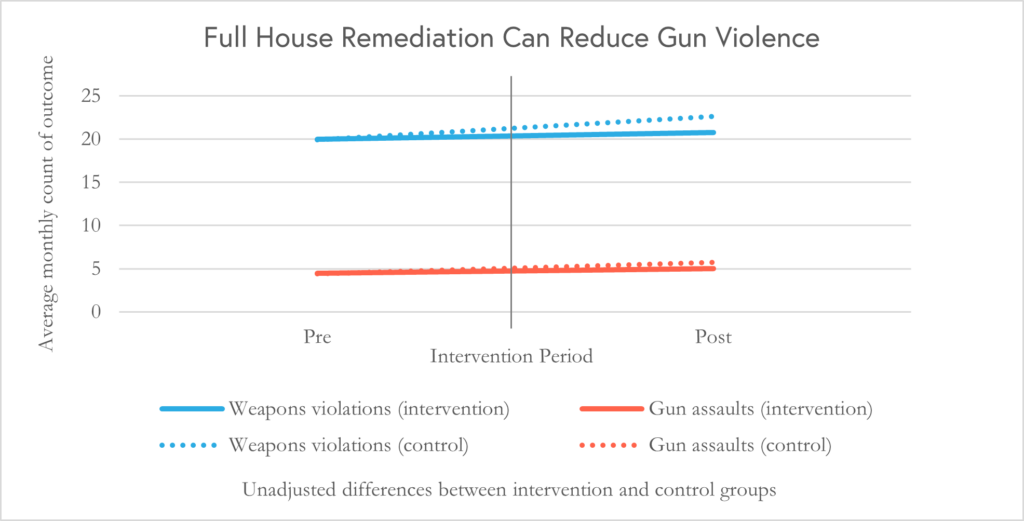

The United States is in the midst of a gun violence crisis, with some of the highest rates of shootings centered in racially segregated urban areas where unemployment is high, and income is low. An ambitious study led by LDI Senior Fellows Eugenia South, John MacDonald, and others, found that one simple reform helped reduce weapons violations, gun assaults, and, to a lesser extent, shootings: remediating abandoned housing in under-resourced Philadelphia neighborhoods. The study results in JAMA Internal Medicine are “very encouraging,” said South and have policy implications for many urban areas, including Philadelphia.

The research stands out for the strength of its findings. While many observational studies have examined the link between vacant and abandoned housing and serious crime, this is the first to involve a randomized controlled trial. The design, like a randomized controlled trial in medicine, allows researchers to draw conclusions about the causal effect of a treatment on an outcome. “In our case, the study helped identify if remediating vacant and abandoned houses with working windows and doors would impact public safety,” explained MacDonald.

The researchers began by randomly sorting a master list of 3,265 abandoned homes in Philadelphia, then formed 63 neighborhood clusters containing 258 abandoned houses. These clusters were randomly allocated to three study arms. In the first group—full remediation—working windows and doors were installed, trash was cleared, and yards were weeded in the vacant houses. A second arm—yard cleaning—included only trash pickup and weeding. The third control arm had no interventions. The study looked at three measures of gun violence in these predominantly Black clusters—weapons violations, gun assaults, and shootings.

A central tenet of the study is that environment has a big impact on people’s day-to-day lives. “Every time we step out of our homes, the places and spaces around us influence our health. The microenvironments that we traverse influence our mood, our train of thought, how we relate to others, and that rolls up to mental and physical health,” South said. More specifically, noted MacDonald, “Having abandoned and vacant houses on one’s block is definitely more than just an ‘eyesore’. Residents have told us on multiple occasions that this is one of the most troubling aspects of perceptions of safety.”

Why would vacant houses affect crime? One plausible mechanism, said MacDonald, is that abandoned houses “are excellent hideouts for illegal activity, like open air drug dealing, that can generate gun violence on street blocks.”. They can also be used as places to store firearms. In addition, write the authors, “these spaces contribute to a stressful neighborhood environment, which may be an antecedent to the escalation of disputes involving firearms, as well as substance trafficking and use.”

The key study finding: “Gun violence actually went up across all arms in the trial but went up the least (to none) in the full remediation arm. So the impact of the intervention is real—it buffered against upward trends in gun violence,” summarized South. However, the intervention had no impact on other measures the group studied, including illegal substance trafficking and use, public drunkenness, and perceptions of safety and time outside for nearby residents.

The researchers also found that yard cleaning alone was not enough to affect crime, despite several studies indicating that “greening” an environment (by, for instance, creating a park on vacant lots) is associated with lower crime. MacDonald explained that despite the litter and weeding around the vacant properties, a lot of litter and trash was still apparent nearby. “I don’t think the treatment was sufficient to detect much of a difference other than the house appearing a bit less disordered in the front area,” he said.

In 2011, the city of Philadelphia instituted a Doors and Windows Ordinance that mandated the installation of doors and windows on abandoned buildings, a policy that has not been widely enforced. “The study offers compelling evidence that Philadelphia should focus more on abandoned houses and compliance with the ordinance,” said MacDonald. “For properties the city owns, they should pay local contractors to install working windows and doors. For owners of vacant houses that don’t have the financial resources to pay for working windows and doors, Philadelphia could have a grants program that would pay for the installation, and when the owner sells the house, they could pay back the investment.”More generally, the research showcases the importance of place-based interventions as opposed to so-called “business-as-usual public health and medical practice.” In a 2014 article in the Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, MacDonald and co-author Charles Branas described this as a practice that focuses on individuals and lifestyle modifications rather than on bigger issues. In the article, MacDonald and Branas, a Penn adjunct professor who’s also the department chair and professor of epidemiology at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, explained what’s wrong with the business-as-usual approach, and why a place-based approach is needed: “Episodically treating small numbers of people, while ignoring the obviously unhealthy social and environmental surroundings within which people live, has stunted our treatments and moved the health of the nation forward at too slow a pace. If done right, place-based programs can potentially become transformational policies for the health and safety of large populations.”

The study “Effect of Abandoned Housing Interventions on Gun Violence, Perceptions of Safety, and Substance Use in Black Neighborhoods: A Citywide Cluster Randomized Trial,” was published in January 2023 in JAMA Internal Medicine. Authors included Eugenia South, John MacDonald, Vicky Tam, Greg Ridgeway, and Charles Branas.

But Many Other Factors Played a Role in Denying Loans, LDI Fellow Says

Offit and Buttenheim Criticize HHS Placebo Trial Mandate as Unethical, Misleading, and a Threat to Vaccine Confidence

A Penn LDI Virtual Seminar Explores the Latest Trends in Anchor Institution Operations

Neighborhood Perceptions May Also Affect PTSD and Depression Recovery After Serious Injury

A Penn LDI and Opportunity for Health Lab Virtual Seminar Explores Economic Assistance Programs

Testimony: Delivered to Philadelphia City Council