Health Care Access & Coverage

News

Health Affairs Journal Convenes Own National Council on Spending and Value

Three Year Initiative Plans Evidence-Based Recommendations for System Changes

The iconic health care policy journal, Health Affairs, has empaneled a 22-member council of top health care researchers, policymakers and business executives to conduct a three-year analysis of why U.S. health care costs so much and how best to change that.

The new Health Affairs Council on Health Care Spending and Value held its first two-day meeting in Washington in late January. Senior Health Affairs Editor and Council Director Laura Tollen, MPH, characterized the initiative as a collective effort in “evidence-based discussion, analysis, and action regarding what we get for our health care spending in the U.S., (and) whether it is worth it.”

Co-chairs Frist and Hamburg

Funded by the National Pharmaceutical Council and the insurance company Anthem, the Council is co-chaired by William Frist, a physician and former U.S. Senate Majority Leader, and Margaret Hamburg, MD, Former Commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Health Affairs is a 38-year-old peer-reviewed scientific journal renowned for its influence among health-related professionals at the highest levels of government, science and business.

Aside from its co-chairs, the Council has 20 other members, including top health care experts from the University of Pennsylvania, Harvard, Johns Hopkins, Northwestern and New York Universities as well the Cleveland Clinic and a number of other health systems and health care-related industries.

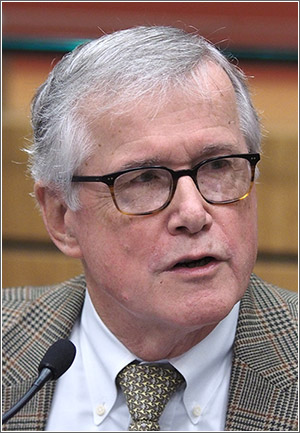

The Penn member on the Council is Wharton School economics professor and LDI Senior Fellow Mark Pauly, PhD.

Consequences of inaction

“I think Health Affairs President and Editor Alan Weil decided to pull together the best people they could find to actually think seriously about spending and value instead of the platitudes we constantly hear about how we’d all like ‘more value at lower cost’,” said Pauly. “The focus is on ‘what do you mean by value?’. ‘What do you mean by cost?’ Essentially the members are looking at evidence and asking what must the country do and what are the consequences of inaction?”

Participants at the first meeting were challenged with addressing a number of issues including the quality of U.S. health care versus its price:

“There is strong evidence,” said a worksheet, “to suggest there are significant ways in which our health spending provides less-than-optimal value. These include, among many others: the persistence of unmet needs (for example, in prevention, mental health and substance abuse care, and chronic disease management); huge unexplained variations in quality and price across the country; and price increases for services and treatments that appear to be driven by market power and nothing more.”

Establishing reliable measures

Pauly said much of the first meeting involved discussions of how to exactly define reliable measures. “There are so many different things that fly under the label of ‘value’ or ‘cost’,” he said. “For instance, economists think ‘costs’ and ‘spending’ are different. If our spending is higher because we’re paying higher wages, that’s different than if spending is higher because we’re using up more resources.”

“A dilemma that arises,” Pauly said, “is the U.S. has worse outcomes than other countries but is that because we’re not spending enough, or we’re not spending well? Or are there other reasons such as the socioeconomic determinants of health that result in far worse outcomes in socioeconomically deprived subpopulations? A lot of our bad results are from our bad social policies that have resulted in people being poor and discriminated against, and not because of the health care system per se.”

‘Can’t have it all’

‘Can’t have it all’

“Another issue,” Pauly continued, “is that some people don’t want to accept the premise that we can’t have it all — their thought is if we just pull up our socks and get our act together we could somehow have higher quality and lower costs. The economist’s version of that is that there is always a tradeoff. That idea — that we may not be able to have it all and may have to decide on what we do want — is part of the charge to the Council.”