Health Care Access & Coverage

Blog Post

How Do Consumers Respond to Surprise Medical Bills?

Hospital switching after labor and delivery

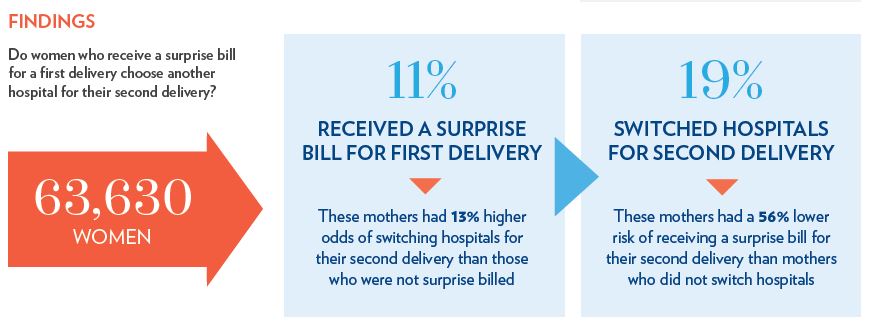

Today, you often hear stories of patients who visit an in-network hospital and still receive a large medical bill because one or more providers involved in their care was out-of-network. Although this phenomenon of “surprise billing” has become common, no research has examined how consumers respond to surprise bills and alter their health-seeking behavior. In our new study in Health Affairs, we investigate how mothers respond to receiving a surprise medical bill after delivering their first child. We find that patients respond to surprise medical bills the same way they respond to bad meals at restaurants: by switching to another facility the next time they need services. Mothers who received a surprise out-of-network bill for their first delivery had 13% greater odds of switching hospitals for their second delivery compared to those who did not get a surprise bill.

What is a surprise medical bill?

After visiting an in-network hospital and seeing an in-network primary physician, patients and families often assume that the entire visit will be covered by their insurance plan. However, our previous research has shown that in one of five emergency inpatient admissions and in nine percent of elective inpatient admissions, the patient is billed by an out-of-network provider when they neither expected nor chose to get out-of-network care. This market failure, where patients cannot possibly shop on the basis of network inclusion, has led to the emergence of state laws to protect patients financially in the event of a surprise out-of-network medical bill.

For example, in New York, patients are held harmless from surprise out-of-network charges beyond their normal co-pay and coinsurance obligation, and an independent entity settles the payment dispute between the insurer and provider. In California, providers are forbidden from “balance billing” patients for out-of-network care that they receive at an in-network facility. And in states like Texas, consumers are turning to a state mediation program to help resolve surprise bill disputes, although the system is not perfect. As our study co-author Christopher Garmon of the Bloch School of Management at UMKC notes, “[r]ight now it’s a patchwork, where some states have protections and others don’t.”

Why did we look at labor and deliveries?

Surprise medical bills for non-emergency labor and delivery are an ideal setting to examine patterns in switching facilities between episodes of care. Because non-emergency labor and deliveries are elective procedures, we can rule out switching hospitals between episodes for reasons unrelated to the bill, such as an emergency that occurred close to a particular hospital. Because the diagnosis is the same, we can also rule out switching hospitals to find different specialists.

We took a nationally representative sample of mothers from a database of employer-sponsored insurance claims and studied women with exactly two births between 2007-2014, restricting to the four most common labor and delivery procedures. We exclude mothers who switch metropolitan statistical areas between births and who do not have more than one hospital in their area offering labor and delivery services. All together, we examine the switching patterns of 63,630 mothers. To capture surprise medical bills in data, we classify surprise bills as deliveries at an in-network hospital with an in-network primary physician or a primary physician not identified, but a secondary provider involved in the patient’s care who is billing out-of-network. This methodology is consistent with our earlier work, as well as our colleagues’ work.

What did we find?

We find surprise bills are associated with increased switching, controlling for factors that affect the likelihood of switching hospitals between births, such as type of birth (cesarean or vaginal), presence of complications or comorbidities, length of stay, and structure of patients’ health insurance, among others.

What are the implications?

Questions exist about how to mitigate surprise medical bills. A recent Brookings report lays out different paths policymakers can take, such as regulating billing and contracting. In the 115th Congress, the House and Senate introduced four bills and one discussion draft to protect patients from various aspects of surprise billing, and the Administration has also expressed interest in tackling the problem.

Our research adds context to the ongoing debate about the best ways to handle the bill when a patient is involuntarily treated out-of-network. For patients, switching hospitals may be an optimal response to receiving a surprise bill in certain circumstances, since those who switched hospitals between deliveries were less likely to receive another surprise bill. But insurers and providers should consider whether a better strategy would be to align network status so that a facility, specialists practicing there, and ancillary services are all in the same network. Policymakers at both the state and federal level should consider laws that protect patients from unavoidable out-of-network bills, and hospital managers should advertise low rates of surprise out-of-network bills at their own institution (if that is the case). Aiming to keep surprise bills infrequent can increase patient retention and satisfaction. And competition on this dimension can reduce the rates of surprise medical bills overall – a boon to patients and their families.

Benjamin Chartock and Sarah Schutz are PhD students in Health Care Management & Economics at the Wharton School and LDI Associate Fellows.