Improving Care for Older Adults

Blog Post

Informal Caregivers and Health Policy

The Case of the Balancing Incentives Program

An estimated 34 million Americans provide informal care to family members or friends, often at high emotional and physical cost. While informal caregivers make up an essential part of the health care continuum, health care policies and payment models rarely take caregivers into account. With growing policy efforts to shift care out of costly institutions and into home and community-based settings, understanding how the increased responsibility affects informal caregivers will only become more crucial.

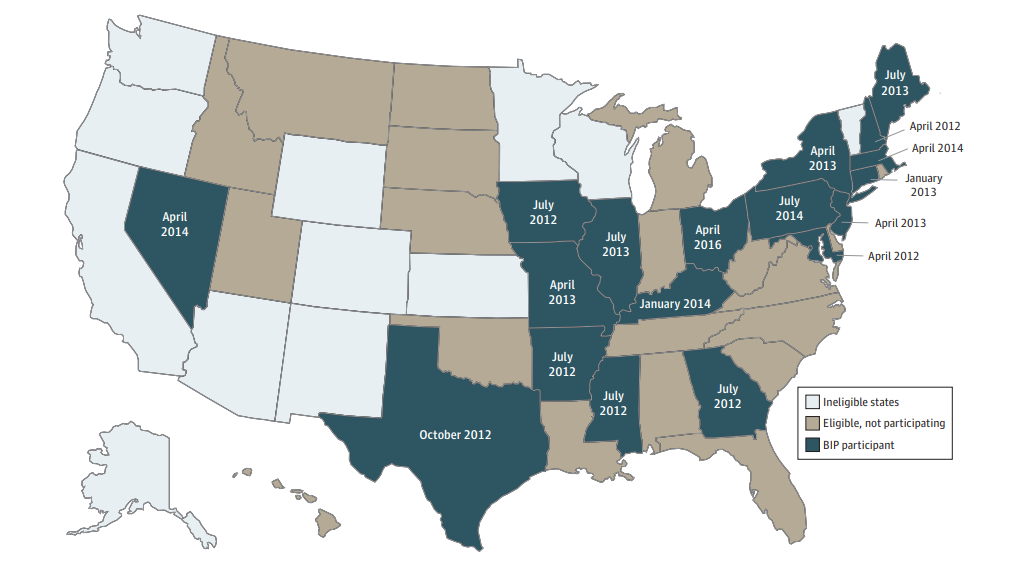

One such policy is the Balancing Incentives Program (BIP), which was established as part of the Affordable Care Act to reduce national spending on long-term care (LTC) for people with functional limitations. BIP was open to 38 eligible states that spent less than 50% of their 2009 Medicaid LTC budget on home and community-based services, of which 18 elected to participate (Figure 1). The program provided $2.4 billion in enhanced Medicaid payments to states to incentivize LTC in home and community-based settings rather than institutions. By doing so, BIP may have increased daily caregiver burdens; however, the additional home-based supports and services funded through BIP could have alleviated some strain on caregivers and led to improved wellbeing.

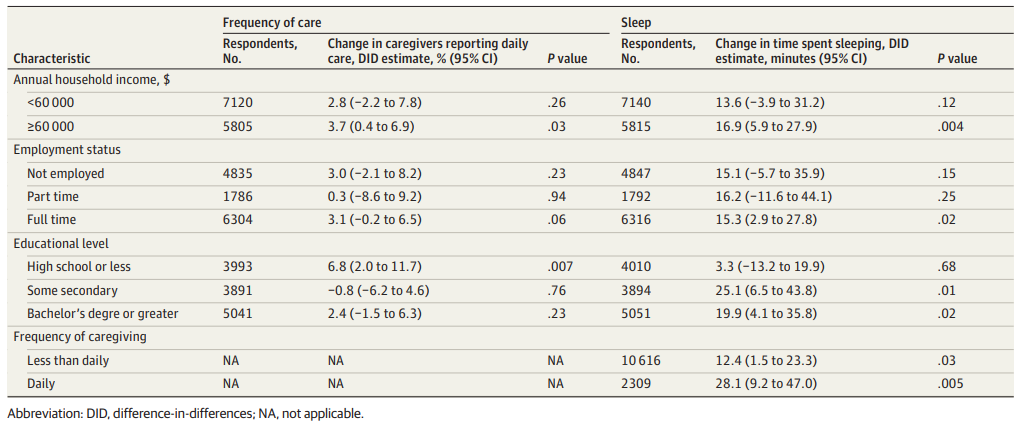

We provide some evidence related to these issues in our new study in JAMA Network Open, which used the American Time Use Survey to evaluate the impact of BIP on informal caregivers. We found that while BIP wasn’t associated with changes in the number of people who reported being an informal caregiver, it was associated with an increase in the frequency of caregiving activities and an increase in caregiver sleep, which is a key marker of wellbeing. While caregivers with fewer years of education saw the most dramatic increase in frequency of care, the benefits of increased sleep accrued mainly to caregivers with higher education and socioeconomic status.

While caregivers of lower socioeconomic status were providing more frequent care after the implementation of BIP, they may not have reaped the benefit of increased home services. For example, caregivers with a high school education or less saw the largest increase in their likelihood of providing daily care, while caregivers with higher levels of education saw no significant change in the likelihood of providing daily care. Furthermore, we found no significant increases in sleep among the lowest-income group of caregivers and those who were unemployed or employed part-time. Caregivers who were fully employed and in the highest income groups did see significant increases in sleep associated with BIP (Figure 2).

These disparities are likely the result of multiple structural forces. First, provision of long-term care at home may be more difficult for low-income seniors who face challenges related to unstable housing and the need for home repairs. Second, new BIP-supported home and community-based services may not be reaching the most structurally marginalized groups of caregivers—prior work has demonstrated that low-income seniors and their families have reduced access to home and community-based services due to lower levels of health literacy, limited transportation and geographic isolation. In contrast, caregivers with higher socioeconomic status and education levels may be more likely to have the health literacy needed to access state-supported programs, resources to pay for additional out-of-pocket care at home, and long-term care insurance.

As policymakers continue to find ways to shift long-term care out of institutional settings and into homes, our findings suggest that a one-size-fits-all approach risks exacerbating existing disparities in caregiver wellbeing. Future policies and programs should focus specifically on understanding and addressing the barriers that low-income seniors and their caregivers face in accessing sufficient, high quality resources to support the delivery of health care at home.

The study, Prevalence of Informal Caregiving in States Participating in the US Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act Balancing Incentive Program, 2011-2018, was first published online in JAMA Network Open in December 2020. Authors include Rebecca Anastos-Wallen, Rachel M. Werner, and Paula Chatterjee.