House Bill Seen Causing 51,000 Preventable Deaths Annually

Penn LDI Seminar Details How Administrative Barriers, Subsidy Rollbacks, and Work Requirements Will Block Life-Saving Care

News

Two scientific papers released in June — one led by LDI Senior Fellows Christina Roberto and Laura Gibson, and the other co-authored by LDI Senior Fellow Norma Coe — present further evidence puncturing two of the loudest claims made by opponents of U.S. sweetened beverage tax programs. Over the last six years since the passage of the beverage tax in Philadelphia, two arguments raised against it are that it eliminates jobs and has an inequitable negative impact across low-income neighborhoods.

A third June paper in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) by a non-Penn research team reporting on a World Health Organization (WHO) commissioned study of sweetened beverage tax programs in the U.S. and 44 other countries found that the taxes consistently lowered product consumption while having no discernible impact on employment.

The Roberto/Gibson paper in JAMA Network Open is a commentary on that WHO report and the two Penn researchers’ own studies. It’s about how beverage tax policies’ potential to negatively impact low-income communities can be offset by the soda tax revenues being invested back into the same communities to fund new and expanded social services.

Roberto, PhD, is an Associate Professor at both the Perelman School of Medicine

and the Annenberg School for Communication, and the Director of the Penn Psychology of Eating and Consumer Health (PEACH) Lab. Gibson, PhD, is a Research Assistant Professor at Perelman and Deputy Director of the PEACH Lab.

The paper co-authored by Coe et. al. in the journal Food Policy, took a more detailed look at the equity burden beverage tax programs may place on low-income populations. The study assessed the tax programs of Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Seattle and was the first to use real-world soda tax data to estimate the tax economic equity impacts.

Coe, PhD, is an Associate Professor of Medical Ethics and Health Policy at the Perelman School of Medicine and Co-Director of the Penn Population Aging Research Center (PARC).

In all three cities, the researchers found the proportion of low-income populations to be smaller than the proportion of higher-income populations. This resulted in the higher-income group paying a larger share of the total soda tax collected. But the amount of total soda tax revenues directly invested back into lower-income communities flipped the picture because it was “a sizable net transfer of funds toward programs targeting lower income populations.”

In advice to policymakers, the researchers concluded that “when considering both population-level taxes paid and sufficiently targeted allocations of tax revenues, a sweetened beverage tax may have characteristics of an equitable public policy.”

Sweetened beverage taxes are designed to be population health interventions. There are 39-42 grams of sugar in single 12-ounce cans of various soda flavors — that’s roughly 75% of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s maximum daily sugar recommendation for people eating a 2,000-calorie-a-day diet.

The latest meta-analysis of the topic’s literature reports: “Sugar-sweetened beverages are the largest source of added sugar in the diet… They have little nutritional value, and a robust body of evidence has linked their intake to weight gain and risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and some cancers.” The occurrence of these diseases is particularly high in low-income communities.

Both the American Medical Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics have endorsed sweetened beverage taxes as an intervention to reduce the overconsumption of sugar.

Further underscoring the health hazard, the WHO report from 45 countries (including the U.S.) noted that people with the same chronic diseases associated with excessive sugar consumption proved to be more susceptible to the most serious COVID-19 infections and death during the current pandemic.

In Philadelphia, the most recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Health Profile of the City found: “Approximately 67.9% of adults and approximately 41% of youth aged 6-17 are overweight or obese. Additionally, nearly 70% of youth in North Philadelphia, the majority of whom are Black or Hispanic, are overweight or obese, which is nearly double the obesity and overweight rate for youth in the United States.”

It was against this background of health demographics that Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney engaged in a brutal 2016 political battle with a national alliance of beverage manufacturers and distributors that poured $10.6 million into the lobbying effort to defeat the City Council beverage tax legislation. But that effort failed, and the city’s sweetened beverage tax was promulgated in 2017. The industry continued to subsequently spend millions more in attempts to get the law repealed. In 2018, a bill was introduced in the Pennsylvania Legislature to prohibit any city in the state from imposing a soda tax, but didn’t pass. A suit to strike down the law was also filed in the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, but the court ruled in favor of the beverage tax.

Currently, Philadelphia and six other cities and the Navajo Nation established sweetened beverage tax policies. Industry’s anti-soda tax lobbying continues across the country against other jurisdictions that are thinking of doing the same.

Since Philadelphia’s law took effect in 2017, the city has taken in a total of $385 million in sweetened beverage tax revenues. The current city budget estimates it will collect $77 million in soda tax revenues this fiscal year.

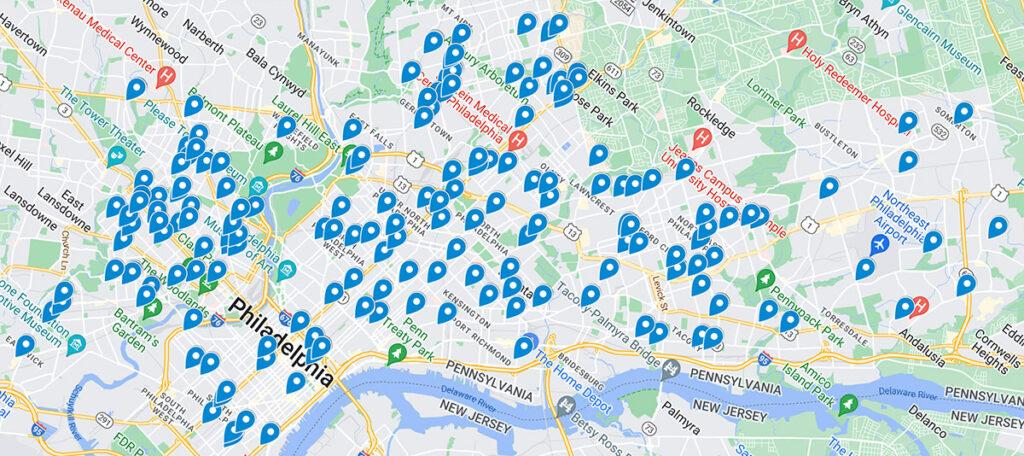

Since 2016, those revenues have funded a citywide network of nearly 180 pre-K locations for 4,300 children, and 17 “Community Schools” attended by 10,000 students in low-income neighborhoods. Last month, the city announced three more schools would be transformed into Community Schools, bringing the total to 20 such facilities.

Last year, funded by the William Penn Foundation and National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER) at the Rutgers Graduate School of Education, a research team evaluated the impact of the Philadelphia pre-K program. Milagros Nores, PhD, NIEER’s Co-Director of Research, told the press:

“Cities like Philadelphia are finding new ways to meet the need for high-quality preschool programs, especially for children in low- and moderate-income families. This study shows that a sweetened beverage tax spent on expanding access to preschool education for low-income families can have a positive net impact on jobs and benefit low-income children and families most, even without considering the health benefits.”

The 20 facilities in the lesser publicized “Community Schools” program funded by beverage tax revenues are elementary, middle, and high schools located in low-resource neighborhoods that have been transformed into hubs of both education and social service supports. The goal is to serve “the whole child.” (See chart) Each school has a full-time coordinator to help students, teachers, parents, and other members of a school community access needed social resources and other programs designed to foster wellness, stability, pride, and a shared sense of purpose and cooperation.

Commenting on the June announcement of the additional three Community School transformations, Philadelphia School Superintendent Tony Watlington Sr., EdD said:

“We know that for schools to help students thrive, we need to work with our partners to address the struggles and challenges our students face inside and outside of the classroom. And that’s exactly why it’s important to have the Community Schools initiative, a collaborative partnership providing wrap-around services and amplifying the work of our Student Support Services to extend our reach far beyond academics.”

Penn LDI Seminar Details How Administrative Barriers, Subsidy Rollbacks, and Work Requirements Will Block Life-Saving Care

Top Experts Warn of Devastating Impact on Community Safety Efforts

A Gathering of a Health Services Research Community Currently Under Siege

1,000+ Detail the Latest Health Services Research Findings and Insights

Wharton and LDI’s Joanne Levy Takes the Stage at AcademyHealth

New Penn LDI Study Is Based on Hospital Incident Reports Rather Than Electronic Health Records