News

Modeling the Deaths vs. Jobs Tradeoffs of COVID Lockdown Policy Options

Wharton School Online Simulator Provides Interactive Projections

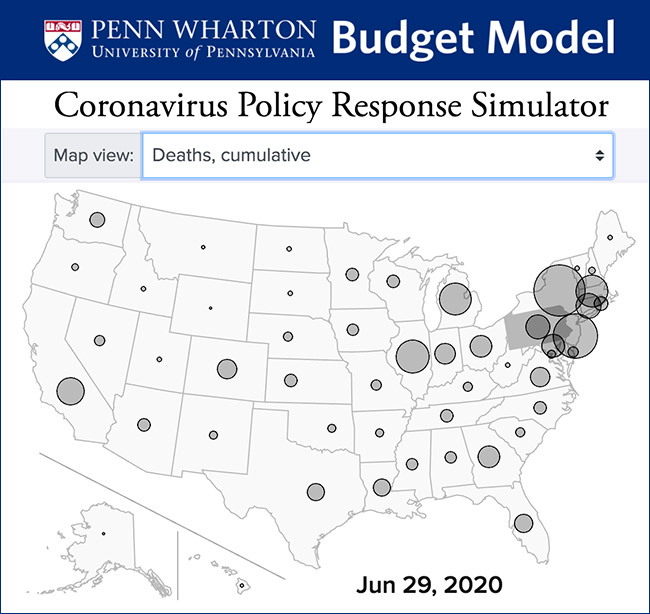

Exactly what are the health vs. jobs tradeoffs of state and federal policies now being proposed to manage the impact of the COVID-19 epidemic? A University of Pennsylvania Wharton School project has created a computer simulation that predicts what various policies might do for both the economy and the death rate.

The worst case scenario says the immediate, complete reopening of U.S. society would result in 233,000 additional COVID-19 deaths but save up to 18,000,000 jobs by the end of June.

The new Penn Wharton Budget Model‘s interactive Coronavirus Policy Response Simulator (CPRS) was demonstrated yesterday in a one-hour LinkedIn video presentation led by LDI Senior Fellow Kent Smetters, PhD, Faculty Director of the Budget Model and Wharton Professor of Business Economics and Public Policy.

The online CPRS system is accessible through a Wharton School web page. It enables users to calculate COVID health and economics tradeoffs nationally or on a state by state basis.

Wharton big-data project

The Budget Model is a Wharton research center where Smetters heads a team of big-data analysts, managers, and programmers usually focused on modeling the economic and societal implications of policy decisions in the annual federal budget. But as the coronavirus pandemic wreaked increasing havoc across the U.S. economy, Smetter’s center turned its attention to studying the health and employment implications of various potential policy decisions — from keeping social distancing and other restrictions as they currently are, partially relaxing them, or completely eliminating them.

“At this point, there’s been no (research) work that has really quantified the tradeoffs between the economic impact and epidemiological outcomes for COVID-19 in a detailed model that shows these tradeoffs between health variables such as deaths and the number of cases, and the GDP and jobs,” Smetters explained to a live audience of 700 LinkedIn viewers. “The work we’re presenting today comes from the new, integrated epi-economic model of the Corona Policy Response Simulator (CPRS).”

Smetters emphasized significant areas of uncertainty in some of the data as the Budget Model team constantly gathers new data and refinines its methods.

Tradeoffs of different policy options

The CPRS essentially focuses on predicting the outcomes of three different COVID policy options over the two-month period from May 1 to June 30: the first is an immediate full reopening, lifting all emergency declarations and restrictions on personal movement and the operation of businesses, schools and entertainments. The second is a partial lifting of the lockdown which ends all emergency declarations, stay-at-home orders and school closings, but keeps other social distancing, business restrictions and safety measures in place. The third is the baseline of conditions that existed throughout the 50 states at the end of April.

“At that baseline,” said Smetters, “we’re projecting that even if states do nothing at all and keep their policies in place as of April 30, and if people do not change their behavior, the number of COVID cases will continue to rise and hit about 2.2 million at the end of June. Deaths will continue to rise. It’s over 65,000 as of today and will continue to rise up to about 116,000 by the end of June.

The other two scenarios predict how many more deaths beyond the baseline 116,000 might occur in full or partial opening. The first prediction is that in a full opening, 233,000 additional people would die during the 60 day period but 18 million jobs would be saved. That’s an average of more than 3,800 additional deaths per day or 158 additional deaths per hour over the period.

Partial reopening policy option

The second prediction is that a partial opening would result in 45,000 additional deaths beyond the 116,000 baseline expectations at the same time it saved about 4.4 million jobs.

Smetters noted that the “saved jobs” are ones that haven’t been lost yet and are in addition to the nearly 30 million jobs that have already been lost as of the end of April.

“Now you can see as the government relaxes and goes to the partial and the full, the number of cases go up, because social distancing goes down; projected deaths go up, but at the same time, you are getting fewer job losses,” said Smetters. “Notice that if you interact the policy scenarios with the behavior element, you get more deaths” because many in the population take behavioral “cues” from policy announcements.

“Maybe you think of a partial relaxation on the policy side or a full reopening on the policy side,” said Smetters. “Sometimes people will take that as a cue that everything is OK and may relax their own personal social distancing.”

Impact of behavioral cues

“We’re not taking a position on how we think people will behave,” Smetters continued. “There’s mixed evidence from different countries. In Hong Kong, for example, when the government started to relax, we saw a lot of reduced social distancing at the personal level. People really took that as a cue that things were OK. But then we saw in other countries where governments did not have a lot of relaxation, or they didn’t have a lot of policy restrictions in the first place, people maintained personal social distancing on their own.”

The first question in the Q&A at the end of the LinkedIn session was about whether the Simulator database contained demographic information about race, ethnicity, and poverty.

Smetters indicated that kind of data had not yet been included in the system.

“There’s no question the anecdotal evidence so far has shown that there’s been differences (in number of coronavirus cases and deaths) by race and socio-economic class for multiple reasons,” he said. “A lot of times these individuals are service workers on the front lines, and a lot of times they don’t have access to hospitals and they’re not going into care early when they’re sick. Those are definitely things we want to get more resolution on over time as we get more data.”