Blog Post

National Survey Reveals Widespread Concern about Risk of Dying, Job Loss During COVID-19 Pandemic

One Week in March When ‘Everything Changed’

From March 10-March 16, 2020, people in the U.S. started to realize that the COVID-19 threat was real, according to a new working paper by LDI Senior Fellows Hans-Peter Kohler, Iliana V. Kohler, and colleagues at Penn’s Population Studies Center. More than 5,400 people answered an online survey about their perceptions of the risks and consequences of the pandemic, as well as any steps they were taking to distance themselves from others. This was the week when identified cases increased from 959 to 4,632, and reported COVID-19 deaths increased from 28 to 85.

Concern grows about infection and dying

Surprisingly, the perception of infection risk was no higher for people living in the three states that had widespread community transmission at the time (Washington, California, and New York) than the rest of the U.S. But perceptions differed by age and education. People in their thirties with a Bachelor’s degree or higher perceived a 50% greater chance of being infected than their less educated peers. Conversely, people with a Bachelor’s degree or higher estimated their chances of dying to be about 8 percentage points lower than those with less education. This education difference diminished among older people, who (accurately) perceived their much greater mortality risks.

There were important temporal trends in these perceptions during the week as well. Analyses showed that the rapid surge in the country’s caseload increased the perceived chances of getting infected with the virus as the week went on.

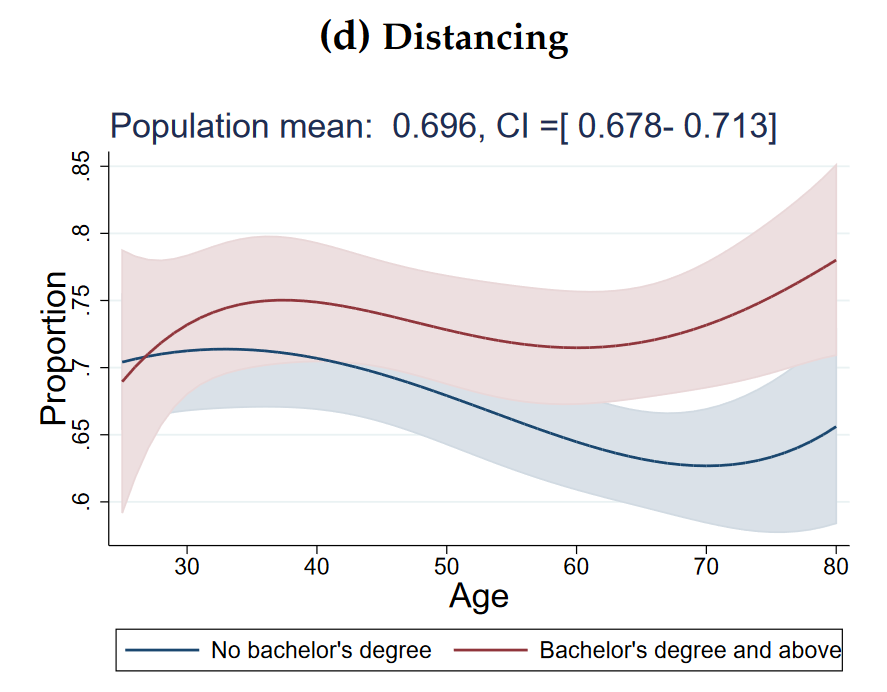

Education, news sources matter in social distancing

About 70% of people in the U.S. reported taking steps to stay away from other people (“social distancing”). While younger and older people report similar rates of social distancing (despite news coverage of young people congregating on beaches and in bars), differences by education emerged for older people. College-educated people were more likely to distance than non-college educated people. Where people get information on the coronavirus also matters: using CNN as a source of information is associated with a 10 percentage point higher chance of engaging in social distancing than using Fox News.

Financial fears are mounting

In the course of one week in March, people began to realize that the pandemic could have drastic financial consequences. As cases mounted during the week across the country, people increasingly thought it likely that they could soon lose their jobs or run out of money.

On average for the week, people perceived that they had a 10% chance to lose their job within three months, and a 13% chance to run out of money in the next three months. These perceptions varied by education level, with younger people holding at least a Bachelor’s degree having about twice lower chances to run out of money compared to others. Women were more concerned about these serious financial consequences than men; women estimated that they had a 16% chance of running out of money within three months.

Why these differing perceptions are important

The researchers note that the survey results are disconcerting, because different perceptions of the reality of the pandemic could threaten the success of our collective societal response. They write:

The [T]he education gradient in expected infection risks entails the possibility of having different perceptions of the reality of the pandemic between people with and without a college education, potentially resulting in two different levels of behavioral and policy-responses across individuals and regions. Unless addressed by effective health communication that reaches individuals across all social strata, some of the misperceptions about Covid-19 epidemic raise concerns about the ability of the United States to implement and sustain the widespread and harsh policies that are required to curtail the pandemic.

The paper, “Know Your Epidemic, Know Your Response: COVID-19 in the United States.” was authored by Alberto Ciancio, Fabrice Kämpfen, Iliana Kohler, Daniel Bennett, Wändi Bruine de Bruin, Jill Darling, Arie Kapteyn, Jürgen Maurer, and Hans-Peter Kohler. It is available as a University of Pennsylvania Population Studies Center Working Paper.