Methadone Use Rises—But Too Few People Get Opioid Medication

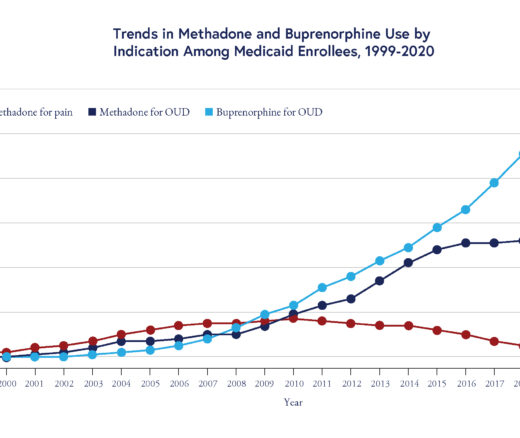

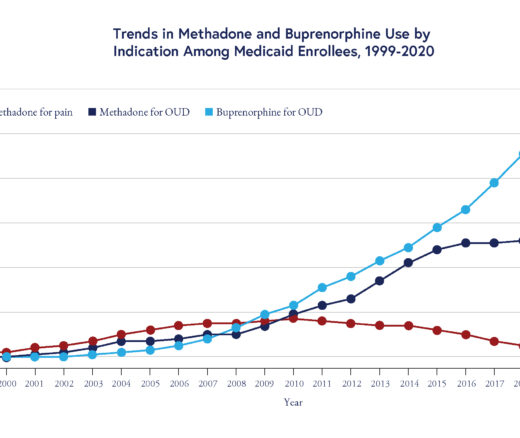

Chart of the Day: Methadone Use for Opioid Use Disorder Tripled From 2010–2020, Yet Only One in Four People With Addiction Receive Medication

Substance Use Disorder

Blog Post

Methadone is known as the gold standard treatment for opioid use disorder, with some experts calling it a “miracle drug” for its effectiveness in blocking the effects of other opioids and preventing withdrawal.

Since 1972, its use has been limited to specialized opioid treatment programs, with patients required to travel to a clinic for daily dosing. This practice was designed for safety but has been criticized as contributing to stigma, and harming individuals’ ability to return to work and other activities to support a healthy recovery.

The COVID-19 pandemic prompted the federal government to temporarily allow take-home doses, a flexibility now granted permanently to states. But today, even as opioid deaths remain at emergency levels, many states and clinics continue to require frequent clinic visits. LDI Senior Fellow Rebecca Arden Harris and colleagues David Mandell, Judith Long, Henry Kranzler, Yuhua Bao, and Jeanmarie Perrone have studied the impact of the federal policy change and discuss the findings and implications below.

We wanted to examine longstanding concerns about the safety and consequences of easing restrictions on methadone dosing for opioid use disorder (OUD). Before the pandemic, federal regulations required most patients to attend opioid treatment programs (OTPs) in person nearly every day to receive their medication under direct supervision, a condition that many patients found burdensome and humiliating. The onset of COVID-19 prompted an unprecedented change in policy: In March 2020, the federal government temporarily allowed patients to take home 14- to 28-day doses. This policy shift created a great opportunity to study the real-world impact of expanded access to unsupervised methadone. We were particularly interested in whether these changes led to increased overdose deaths—a major concern that has long divided stakeholders, policy-makers, and experts. We also wanted to know whether the effects varied across racial, ethnic, or geographic lines. Our goal was to generate empirical evidence to help inform methadone policy so that future regulations are guided by data rather than assumptions.

The Food and Drug Administration approved methadone as a treatment for OUD about 50 years ago, at which point the federal government designated specialized opioid treatment programs (OTPs) as the only authorized providers—a strategy designed to centralize control of the drug, maintain treatment quality, and protect public safety. While OTPs remain the exclusive source of methadone for addiction treatment, the research evidence emerging from the pandemic prompted the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) to make the take-home dosing flexibility permanent. However, states may choose to impose stricter rules, and clinicians still have wide discretion to determine take-home eligibility based on clinical criteria. As a result, access to take-home methadone remains inconsistent, varying significantly by state and even by clinic.

Across three studies, our research team found that the COVID-19 policy allowing extended take-home methadone doses did not increase methadone-involved overdose deaths overall. Both states that permitted take-home doses and those that did not showed similar changes in mortality trends from the pre- to post-policy periods. However, some rural counties experienced increases in methadone-involved overdoses, likely due to unique factors such as limited access to health care and fewer harm reduction resources. The research directly counters concerns about widespread overdose deaths. Findings also suggest that expanded take-home access reduced barriers to treatment and improved patient autonomy, with deregulation especially beneficial for marginalized groups such as Black and Hispanic men. These studies, alongside the work of other researchers, provide population-level evidence in support of more flexible, patient-centered methadone policies. They also underscore the need for further research into regional disparities and long-term impacts.

The group of states that did not permit extended take-home methadone doses was small, limiting the ability to control for potential confounders. The studies could not determine whether individuals who died from methadone-involved overdoses had received methadone from opioid treatment programs, from prescriptions for pain, or through diversion, since death certificates do not specify the source. Additionally, about 5% of death certificates did not list the drugs involved, potentially leading to undercounting or misclassification of methadone-involved deaths. The abrupt increase in methadone mortality observed in March and April 2020 likely reflects broader pandemic-related disruptions, which complicates attributing changes specifically to the policy. Finally, the findings may not fully capture local variation, such as differences in implementation across and within states. Further research is needed to address these gaps.

Based on our findings and the work of many other researchers, policymakers at both the state and federal levels should support the continued expansion of flexible take-home methadone policies. States currently have the authority to allow extended take-home doses, but some are not using this flexibility. Policies under consideration in Congress, such as the Modernizing Opioid Treatment Access Act (MOTAA), would further lower barriers to methadone treatment for OUD by allowing specially trained physicians to prescribe methadone through retail pharmacies. Finally, additional support and harm reduction resources should be directed to rural communities, where long distances, limited health care providers, and unique social challenges make accessing treatment especially difficult.

We aim to investigate the factors driving state and OTP decisions to restrict or expand take-home methadone privileges, including political, economic, and social influences. We also need studies to assess the long-term impacts of these policies on patient outcomes, such as treatment retention, return to use, and quality of life, and identify disparities in implementation and effects across demographic groups and geographic regions.

The study “Methadone-Involved Overdose Deaths in Urban and Rural Communities Before and After the Public Health Emergency Flexibilities for Methadone Take-Home Doses” appeared in the June 2025 issue of Drug and Alcohol Dependence Reports. Authors include Rebecca Arden Harris, Judith A. Long, Henry R. Kanzler, Yuhua Bao, Jeanmarie Perrone, and David S. Mandell.

The study “Methadone Take-Home Policies and Associated Mortality: Permitting versus Non-Permitting States” by Rebecca Arden Harris appeared in Substance Use: Research and Treatment on August 16, 2024.

The study “Racial, Ethnic, and Sex Differences in Methadone-Involved Overdose Deaths Before and After the US Federal Policy Change Expanding Take-home Methadone Doses” appeared in JAMA Health Forum on June 9, 2023. Authors include Rebecca Arden Harris, Judith A. Long, Yuhua Bao, Jeanmarie Perrone, and David S. Mandell.

Chart of the Day: Methadone Use for Opioid Use Disorder Tripled From 2010–2020, Yet Only One in Four People With Addiction Receive Medication

LDI Fellows Used Medicaid Data to Identify Individuals at Highest Risk for Cocaine- and Methamphetamine-Related Overdoses, Paving the Way for Targeted Prevention

Penn and Four Other Partners Focus on the Health Economics of Substance Use Disorder

Penn Medicine’s New Summer Intern Program Immersed Teens in Street Outreach Techniques

LDI Experts Offer 10 Solutions to Get More Help to Seniors With Addiction

Research Brief: LDI Fellow Recommends Ways to Increase Availability