Blog Post

#OldBoysClub: How Academic Twitter May Perpetuate Gender Disparities in Health Services Research

Female researchers garner fewer followers, retweets and likes

Outside of the brick and mortar walls of academic institutions—and conferences attended by researchers — there is an invisible conversation happening. Academic Twitter, as it’s affectionately known, is a world unto itself. Yet, it turns out, there are ways in which it bears a striking resemblance to the familiar “old boys’ club.”

In a new JAMA Internal Medicine study of Twitter users, LDI Executive Director Rachel Werner, Senior Fellows Jane Zhu and Raina Merchant, and colleagues find that female health services and policy researchers had considerably less reach and influence on the social media platform than their male counterparts. The study suggests that the Twitterverse may be plagued by some of the same gender dynamics as traditional academic forums.

Offline, gender bias and disparities between men and women in academia are readily apparent. Women in academic medicine report experiences ranging from subtle messages that downplay their accomplishments (for example, being called by a first name instead of a professional title) to discrimination and sexual harassment.

This climate may explain, in part, why women have difficulty finding effective mentors and receive lower levels of institutional resources. As a result, their careers trail behind men: they’re less likely to author original research or guest editorials (particularly as first author) in major journals, speak at national medical conferences, receive prestigious awards or assume leadership positions.

In this context, social media provides women with an inclusive and convenient platform for networking, and an opportunity to gain visibility and promote their work. It is easy to imagine how social media could help level the playing field for female researchers given that signing up for Twitter and other social media sites does not require an invitation or sponsorship.

In their study, the authors identified speakers and co-authors of research presented at AcademyHealth’s 2018 Annual Research Meeting, the nation’s largest health services research conference. All non-trainee researchers with an MD, PhD or equivalent employed in the United States were included in the study. Of 3,148 researchers, 53% were women and 47% men. Rates of Twitter use were similar among women and men, with about 1 in 3 using the platform.

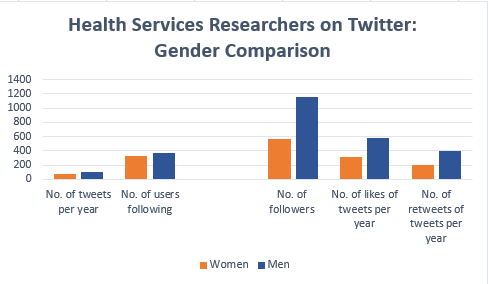

While on average, women and men had a similar number of tweets per year and followed a similar number of other Twitter users, women had been on Twitter for fewer years than men (4.5 vs. 5.1).

Despite similar levels of engagement, female researchers had substantially less reach and influence on Twitter than their male colleagues, as measured by average numbers of followers, likes, and retweets. Women had half the number of followers of men (567.5 vs. 1162.3). And their tweets generated significantly fewer likes (315.6 vs. 577.6) and retweets (207.4 vs. 399.8) per year.

Women were more likely to follow other women, compared to men: 54.8% of Twitter users who women followed were female, compared to 42.6% of users men followed. And women were more likely to be followed by women: 58% of the people following women on Twitter were female, compared to 48.1% of the people following men.

But there’s good news: things may be changing for the next generation of health services researchers. Differences in reach and influence between women and men were smallest for assistant professors – those just beginning their academic careers – and most pronounced for full professors. These results suggest that younger cohorts of researchers may be on the path to gender parity — at least, online.

Nonetheless, this study’s finding that – despite similar levels of use – women and men had substantially different levels of reach and influence on Twitter is disconcerting. Participation on Twitter improves the dissemination of research and holds the potential to advance the work (and careers) of researchers in new ways. It is possible that gender disparities on Twitter will only reinforce and amplify existing disparities in academics.

While its conclusions echo experiences reported by women offline and on other social networks, this research appears to be the first examining gender differences within Twitter’s academic medical community. The authors’ findings suggest that social media may be no better at promoting women than other academic settings. In short: life reflects Twitter and Twitter reflects life.