Health Care Access & Coverage

Blog Post

Revisiting CHIP Buy-In Programs for Children

[Original post: Megan McCarthy-Alfano et al., Revisiting CHIP Buy-In Programs for Children, Health Affairs Blog, February 14, 2020. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200207.195893/full/. Copyright ©2020 Health Affairs by Project HOPE – The People-to-People Health Foundation, Inc.]

Once a casualty of the battles to pass the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the “public option” has reappeared in the current health reform debate. While details differ, public option proposals share the belief that giving people the choice to buy a government-sponsored plan can improve access and coverage.

This concept is not new; in some states, a public option for children has existed for decades. In this post, we examine the current status of buy-in programs that allow families whose income exceeds the eligibility limit for Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) to purchase public coverage for their children.

Although few states have been able to maintain viable and vibrant buy-in programs, there are reasons to revisit them now. First, progress toward universal coverage for children is reversing, with the number of uninsured children increasing by more than 400,000 in recent years. Second, private insurance for children on the ACA’s Marketplaces and employer-sponsored family coverage often comes with premiums and deductibles that are increasingly burdensome for moderate-income families, particularly those raising children with special health care needs. By contrast, families “buying in” to public programs can receive the comprehensive, child-specific benefits offered through Medicaid’s Early and Periodic Diagnostic, Screening, and Treatment benefit (EPSDT), and in most CHIP programs, at relatively small or no copayments. Finally, the latest CHIP reauthorization—the HEALTHY KIDS Act of 2018—clarifies ACA requirements that previously impeded some buy-in programs and offers states new flexibility for these plans.

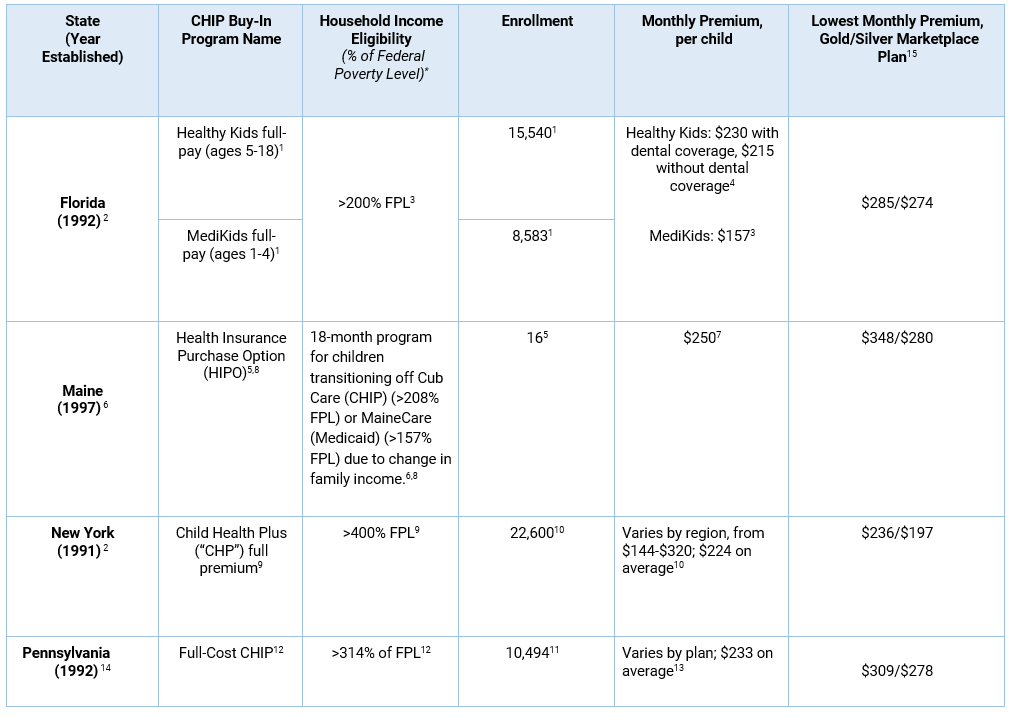

Here, we review states’ experiences with CHIP buy-in programs in the years since the ACA and present updated information on the four remaining programs. We gathered program information from think tank publications, state government websites, and press releases, as well as communications with state agencies, child advocacy groups, and congressional staff via phone and email.

To assess whether CHIP buy-in offers families an affordable alternative to individual market coverage, we compared 2019 premiums for CHIP buy-in plans to child-only premiums on the federal and state Marketplaces. After presenting those results, we conclude by considering lessons from past and current buy-in programs; we describe design features that have proven successful and that states should consider incorporating in their buy-in options for children moving forward.

Historical Landscape Of Child Buy-In Programs

Pre-ACA

As of January 2011, at least 15 states (Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and Wisconsin) offered a Medicaid or CHIP buy-in program to families whose income exceeded their state’s Medicaid or CHIP eligibility limits. While traditional Medicaid and CHIP are subsidized through a federal-state partnership and offer coverage at small or no premiums, families with buy-in coverage are typically responsible for the full cost of their monthly premium.

States designed their buy-in programs to target specific income groups or families at risk. For example, Maine and North Carolina provided only time-limited, transitional coverage to children on public coverage who were ineligible for renewal because their family income increased. Some states minimized the likelihood that a buy-in program would “crowd out” private insurance by implementing waiting periods or requiring that no other affordable insurance was available for the child. Prior to the ACA, buy-in programs offered a coverage option to moderate-income families whose child had been turned down by commercial insurers due to a preexisting condition.

Although buy-in programs were intended to expand coverage for uninsured children, many suffered from poor take-up and low enrollment. For example, Connecticut’s program had 191 enrollees when it ended in 2015; Ohio had seven. In some states, buy-in options were not well-known or targeted only a small sliver of uninsured children; in others, full-cost coverage remained unaffordable for moderate-income families.

All but four states (Florida, Maine, New York, and Pennsylvania) ended their Medicaid/CHIP buy-in programs in the past decade. Five other states offer a Medicaid buy-in only for children with special health care needs, under a different pathway described below.

Post-ACA

The ACA affected buy-in coverage in a number of ways. Community rating and guaranteed issue provisions gave previously uninsurable children new options for coverage. Moderate-income families (up to 400 percent of the federal poverty level) were eligible for subsidized private plan premiums on the new state and federal Marketplaces. In the face of new coverage options, some states decided that buy-in programs were no longer needed.

The ACA’s new benefit requirements also complicated the administration of buy-in programs. The law required qualified private plans to provide “minimum essential coverage,” newly defined by 10 essential health benefits, and elimination of most annual and lifetime limits. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) recognized traditional Medicaid and CHIP plans as meeting these standards, even though some states had annual or lifetime limits on benefits such as behavioral health care.

CHIP buy-in plans, however, fell into a regulatory gray zone, in which CMS determined whether each plan met the new standards for private qualified health plans. Some states, such as New Jersey, chose to end their buy-in program rather than incur the costs of increasing benefits to meet the standards. As explained later, Florida’s buy-in premiums rose dramatically as a consequence of these requirements.

The HEALTHY KIDS Act of 2018 created new flexibility for states to pursue CHIP buy-in programs. First, it specifies that buy-in programs are considered minimum essential coverage as long as they offer benefits that are at least identical to the state CHIP plan. Second, it clarifies that states can develop CHIP buy-in rates based on a combined risk pool with their subsidized CHIP population. This allows the potentially higher costs of the buy-in population to be spread across a larger pool, stabilizing buy-in premiums.

Current CHIP Buy-In Programs

Four states have continued their CHIP buy-in programs. We review each program below and summarize our findings in exhibit 1. All program information reflects estimates as of August 2019, at the time we conducted this research.

Sources: 1. Kenney GM, Blumberg LJ, Pelletier J. State buy-in programs: prospects and challenges. Washington (DC): Urban Institute; 2008 Nov 24. 2. Healthy Kids. Florida’s uninsured, eligible and enrolled children. Tallahassee (FL): Healthy Kids; 2019 Jul. 3. Florida KidCare. Florida KidCare Income Guidelines. Tallahassee (FL): Florida KidCare; 2019 Apr. 4. Healthy Kids. Full-Pay Program. Tallahassee (FL): Healthy Kids; 2020. 5. Maine Department of Health and Human Services, Office for Family Independence. Chapter 335: Health insurance purchase option, sections 1-2. Augusta (ME): Maine HHS; 2010. 6. Consumers for Affordable Health Care. MaineCare Eligibility Guide. Augusta (ME): Maine Equal Justice Partners; 2018 Jun 14. 7. Number enrolled during 2019 plan year. Communication with Maine Department of Health and Human Services, 2019 Aug. 8. NY State of Health. NY State of Health 2019 Open Enrollment Report. New York (NY): NY State of Health; 2019 May. 9. Communication with New York State of Health, 2019 Aug. 10. Pennsylvania H.B. 20, No. 1992-113. 11. Pennsylvania’s Children’s Health Insurance Program. CHIP: Eligibility and Benefits Handbook. Harrisburg (PA): Pennsylvania Department of Human Services; 2017 Apr 5. 12. Communication with Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, 2019 Aug. 13. Pennsylvania’s Children’s Health Insurance Program. PA CHIP Income Guidelines Chart. Harrisburg (PA): Pennsylvania Department of Human Services; 2019 Feb. 14. We searched for 2019 plan premiums for Healthcare.gov states (Florida, Maine, and Pennsylvania) in Miami Dade County, Florida; Cumberland County, Maine; and Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania, for a 12-year-old female with an average family income of $87,453 (401 percent of poverty), just above the cutoff for subsidy eligibility. We identified statewide, child-only plan premiums for New York’s state-based exchange using the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation HIX Compare Database. *Eligibility levels do not include the 5 percent income disregard.

Florida

Florida has one of the oldest and largest CHIP buy-in programs still in existence, with more than 25,000 enrollees. It offers two types of coverage: Healthy Kids full pay (children ages 5–18) and MediKids full-pay (children ages 1–4). Eligibility starts for children with family incomes above 200 percent of poverty, the state’s upper limit for subsidized CHIP.

Florida’s post-ACA experience with buy-in is particularly instructive for states. Until October 2015, the Healthy Kids buy-in population and subsidized Healthy Kids populations were in a combined risk pool. The Healthy Kids program offered two tiers of buy-in coverage: “Sunshine Health Stars Plus” and “Sunshine Health Stars.” Sunshine Health Stars Plus (which was equivalent to a platinum-level plan) offered more comprehensive coverage than Sunshine Health Stars, with no deductible and small copays.

However, premiums in the Healthy Kids buy-in program rose nearly 60 percent when CMS determined that Florida’s buy-in program did not meet minimum essential coverage requirements and the state separated its subsidized CHIP and CHIP buy-in risk pools. Florida ended the “Sunshine Health Stars Plus” program at the end of 2016 because it became too expensive to maintain, and nearly 10,000 buy-in enrollees lost coverage.

Although Healthy Kids buy-in enrollment is slowly climbing back to pre-ACA levels, the state acknowledged that coverage was still too costly for many families. Healthy Kids full-pay families pay $230 per child per month with dental coverage and $215 per child without dental coverage. MediKids full-pay families pay $157 per child per month. Families’ out-of-pocket costs were also significant. Until January 2020, Healthy Kids full-pay families had a $3,000 medical deductible and $1,500 pharmacy deductible per child. Copays ranged from $5 for vision to $100 for emergency services; for other services, families were responsible for 25 percent coinsurance after their deductible. Out-of-pocket costs were capped at $4,250 and $2,350 for medical and pharmacy services, respectively, which did not include monthly premiums. By comparison, most families in subsidized CHIP pay a $15 or $20 monthly premium per family and have little or no copays.

In the wake of the latest CHIP reauthorization, Florida has now recombined its Healthy Kids buy-in and traditional CHIP risk pools. In effect, the state has “cross-subsidized” buy-in costs through risk pooling; the additional costs for the traditional CHIP population will be covered by more than $1 million in state funds and about $6 million in federal matching funds. While these financial mechanisms may be complex, the benefits for buy-in families are clear: As of January 2020, Florida has eliminated all coinsurance and deductibles and lowered copays. The state estimates that Healthy Kids buy-in enrollment will more than double by July 2020, making up 15 percent of the total Healthy Kids enrollment.

Maine

Established in 1997, Maine’s Health Insurance Purchase Option offers transitional, COBRA-like coverage to children who lose their eligibility for Medicaid or CHIP coverage due to a change in family income. Children can qualify for the program under two scenarios: their family income exceeds the state’s CHIP (Cub Care) limits by the end of their 12-month enrollment in CHIP, or they are enrolled in Medicaid (MaineCare) and their family income exceeds both Medicaid and CHIP limits when their eligibility is reviewed. By law, enrollment is limited to 18 months.

Premiums are set by averaging enrollees’ monthly costs for the previous two years and adding 2 percent for administration. They also must be revenue-neutral for the state. At this writing, families have a monthly premium of $250 per child, compared to $8–$64 in subsidized CHIP. Given the substantial increase in premiums between subsidized and full-cost coverage as children transition off of Medicaid and CHIP, it is not surprising that the Maine buy-in program has had very little take-up in its more than 20-year history. It is also likely that many of the families transitioning off of public coverage are newly eligible for employer-subsidized family coverage, which could be more affordable than full-cost CHIP (if employer contributions and tax breaks are considered).

New York

New York’s CHIP buy-in program (Child Health Plus full premium) has operated since 1991. The state now has the second-largest CHIP buy-in population with 22,600 enrollees, or roughly 5 percent of its total CHIP population. Monthly premiums vary by region but average $224 per child.

New York previously targeted its buy-in program to children in families with incomes above 250 percent of poverty, the state’s upper limit for subsidized CHIP. However, in 2008, New York expanded eligibility for its subsidized CHIP program to children with family incomes up to 400 percent of poverty. By shifting buy-in eligibility to higher-income families, the state targeted families who are more able to afford the full-cost premiums. Since 2005, enrollment has grown by more than 10,000 kids, making the program one of the most robust in the country.

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania’s CHIP program began in 1992 and became the model for the federal program. The state’s CHIP buy-in program (Full-Cost CHIP) began at the same time. Like New York, Pennsylvania shifted buy-in eligibility (from children in families with incomes above 235 percent of poverty to those in families with incomes above 300 percent of poverty) when it expanded subsidized CHIP in 2007 as part of a push to achieve universal coverage for kids. Currently, buy-in eligibility begins at family incomes greater than 314 percent of poverty, and monthly premiums vary according to the plan a family chooses.

The average premium across the state is $233 per child, and copays range from $10 for generic prescriptions to $50 for emergency department visits. In comparison, monthly premiums range from $53–$84 in subsidized CHIP. Now at 10,494 enrollees, Pennsylvania’s buy-in population has increased by roughly 2,400 kids since December 2017 and represents just below 6 percent of the state’s total CHIP population.

In 2015, Pennsylvania negotiated a delay with CMS to exempt CHIP buy-in plans from minimum essential coverage requirements for one year and prevented thousands of children from losing coverage. In the interim, Pennsylvania worked with insurers to modify plans to meet the new standards.

Comparison To Child-Only Marketplace Coverage

We explored whether CHIP buy-in offers a more affordable premium for families than unsubsidized, child-only coverage on the health insurance marketplaces. While a full analysis of marketplace plans lies beyond the scope of this post, we looked at the lowest-premium gold and silver plans in three major counties in the Healthcare.gov states (FL, ME, and PA) for a 12-year-old child with a family income over 400 percent FPL, above the cutoff for subsidy eligibility. For New York – which operates a state-based exchange – we identified the lowest-premium gold and silver child-only plans on the state marketplace using the RWJF HIX Compare database. Since platinum plans (when offered) would be prohibitively expensive for moderate-income families, we did not include them in our comparison.

In general, during plan year 2019, CHIP buy-in premiums were less expensive than unsubsidized, child-only premiums in Florida, Maine, and Pennsylvania. Across the states, the lowest-cost silver plan was about $30–$60 more expensive per month than CHIP buy-in coverage, while the lowest-cost gold plan was about $60–$100 more expensive. In New York, price differences were less stark: The lowest-cost, child-only silver plan was $27 less expensive per month than the average CHIP buy-in premium, while the lowest-cost gold plan was only $12 more expensive per month.

Florida’s buy-in program should be an even better deal for families now that the state has implemented its new policies to eliminate deductibles and lower copays. While our analysis did not include cost sharing or benefits, compared to Marketplace coverage, CHIP generally offers lower copays and more generous benefits that are better tailored to children’s needs. Thus, our findings raise the question of whether a state may be able to offer families better pediatric coverage at lower costs through a buy-in program.

Buy-In For Children With Special Health Care Needs

A number of states also offer Medicaid buy-in programs to children with special health care needs when their family income exceeds Medicaid eligibility limits. For instance, five states (Colorado, Iowa, Louisiana, North Dakota, and Texas) offer a Medicaid buy-in option to children with special health care needs whose family income is less than 300 percent of poverty under the Family Opportunity Act (FOA).These programs allow children to access Medicaid’s comprehensive EPSDT benefit. FOA states can charge premiums up to 7.5 percent of family income, although some states do not charge any. Unlike CHIP buy-in, Medicaid buy-in under the FOA primarily serves as secondary, supplemental insurance for privately insured children with special health care needs who require more comprehensive coverage.

Outside of the FOA, Massachusetts also offers a Medicaid buy-in to families of children with special health care needs starting at income above 150 percent of poverty. The program has no income limit but a graduated premium schedule.

Considerations For States: Revisiting Buy-In

The lessons learned from previous and current child buy-in programs are instructive for states as they think about expanding coverage for children or other populations. Here, we highlight important design elements of successful buy-in programs that state policy makers should consider in a full-cost buy-in option for children and that should guide them in constructing subsidies for populations for whom a full-cost option may not be affordable.

States Can Use Buy-In Programs To Address Critical Gaps In Coverage For Remaining Uninsured Populations

Medicaid or CHIP buy-in can fill a void for moderate-income families who do not have access to employer-sponsored insurance and are not eligible for public coverage. Our limited analysis reveals that buy-in plan premiums are less expensive for families than unsubsidized, child-only coverage on the Marketplaces. Overall, an extra monthly cost of $30–$100 per child for child-only coverage can quickly add up and become a significant burden for moderate-income families. Additionally, buy-in programs often have “platinum-level” benefits that would be unaffordable for families on the Marketplaces.

States Must Also Consider That A Full-Cost Public Insurance Option Is Not Necessarily Affordable For All Families Without A Subsidy

Florida’s experience in particular demonstrates the price sensitivity of families eligible for CHIP buy-in, large numbers of whom dropped coverage as costs increased. For many families, buy-in coverage may only be affordable if it is subsidized, either directly or indirectly through combined risk pools. Paying full-cost premiums and cost sharing could be particularly challenging for families seeking to cover multiple children or those with special health care needs, so subsidies should be designed with these populations in mind.

States Should Combine Risk Pools For Their Buy-In Population And The Broader Medicaid/CHIP Population

The HEALTHY KIDS Act explicitly permits states to combine their CHIP buy-in and subsidized CHIP risk pools. By broadening the size and the composition of the risk pool, states not only can benefit from administrative efficiency but can also lower buy-in costs by minimizing adverse selection. Due to this new flexibility, New Jersey policy makers considered reviving its buy-in program. The HEALTHY KIDS Act presents an opportunity for other states to do so as well.

States Considering Buy-In Should Also Consider Extending Eligibility For Subsidized CHIP

As of January 2019, 30 states limit CHIP eligibility to 200–300 percent of poverty, and two states limit it to below 200 percent of poverty. However, buy-in programs are not likely to be affordable for families at the low end of the income scale. New York and Pennsylvania’s experiences demonstrate that as eligibility for subsidized CHIP increases, buy-in enrollment increases because the full-cost premium presents less of a barrier to higher-income families. Given that enrollment in buy-in has historically been low, states should take steps to better understand who is most likely to benefit from buy-in programs and to target their programs to families at the higher end of the moderate-income scale.

States Must Ensure That Buy-In Programs Are Sufficiently Marketed And Targeted

Merely offering a public option buy-in does not guarantee program success. States must sufficiently market their programs and conduct consumer outreach so individuals are aware of the buy-in option. Further, as Maine and North Carolina’s experiences demonstrate, policymakers must ensure that their programs target the right population to be successful; few consumers have enrolled in transitional programs that target families previously in Medicaid or CHIP, possibly because these families have access to employer-sponsored insurance as their incomes rise.

The nation has taken in its progress toward universal coverage of children, and marketplace plans have not eliminated the need for affordable, comprehensive insurance. Child buy-in programs deserve another look, particularly in light of the opportunities presented for states in the HEALTHY KIDS Act. Policymakers interested in pursuing a public option for children can learn from states’ experiences with buy-in programs and assess how this policy lever could serve families who have fallen into the coverage gap. Properly designed, targeted, and marketed, buy-in programs could be a cost-effective way of moving toward universal coverage for children.

Authors’ Note

The authors thank their contacts at the state agencies and advocacy organizations who provided them with information for this piece, especially those in the Florida, Maine, New York, and Pennsylvania Medicaid and CHIP programs.