Health Care Access & Coverage

News

Scope of Practice Restrictions and Vulnerable Populations

LDI Virtual Conference Explores The Issue's Changing Dynamics

A key point emerging from the “Expanding Scope of Practice After COVID-19“ virtual conference on November 20th was that the pandemic’s devastating effects have presented a new opportunity to help change the SOP restrictions that have long hampered efforts to provide more and better care for underserved populations.

Dozens of states have temporarily relaxed SOP limitations on advance practice registered nurses (ARPNs) to augment beleaguered front-line clinicians at medical facilities overwhelmed by coronavirus. The question now is this: after the pandemic has passed, will it make sense to again impose limitations that will pull back APRNs from the very communities that were most ravaged by the disease and its long-term effects?

“COVID-19 has shown a very bright spotlight on how restrictive scope of practice regulations affect public health across health professions,” University of Pennsylvania Nursing School Dean and LDI Senior Fellow Antonia Villarruel, PhD, RN, FAAN, told the audience. “Should we allow professional oversight of one profession by another? Can we ensure post-pandemic that the skills and abilities of all health professionals are not hampered by unnecessary regulations, and that we are all engaged in providing accessible and equitable care?”

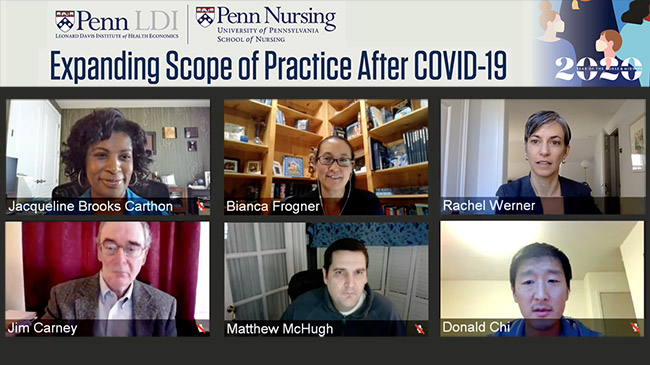

Convened by Penn’s Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics (LDI) and the Penn School of Nursing, with support from Penn Law and Penn Dental, the virtual conference brought together 15 top national experts in every aspect of the state laws that have long prevented APRNs, physician assistants, and dental hygienists from practicing to the full extent of their expertise.

Year of the Nurse 2020

Organized late last year before the outbreak of coronavirus, the conference was one of a series of special events designed to mark the International Year of the Nurse and the Midwife 2020. But it took on new meaning as the pandemic ripped across the country, overwhelming health systems and triggering the emergency relaxation of SOP restrictions.

These same state actions have created a natural experiment that will likely produce important data about the effectiveness and economics of allowing APRNs to operate to the full extent of their expertise in the midst of the most severe public health emergency of the last century.

“What we’re talking about in this seminar is the gathering of evidence and the thinking about the law and more permanent ways to expand scope of practice so that the health care workforce, and what these professionals are able to do, better matches the needs of the population,” said Penn Law Professor Allison Hoffman. Hoffman, JD, who moderated the “Reforming Scope of Practice to Meet Community Needs” panel discussion.

Keynote speaker Martin Gaynor picked up on the same theme of SOP law and the importance of evidence. Gaynor, PhD, is a Professor of Economics and Public Policy at Carnegie Mellon University and former Director of the Bureau of Economics at the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC). He is one of the country’s top scholars on market incentives, competition and antitrust policy and enforcement.

‘A great deal of contention’

“Scope of practice laws have been the subject of a great deal of contention,” said Gaynor. “I’m going to approach this from a perspective of economics and competition policy or antitrust. Our antitrust economics perspective for laws or regulations that restrict competitors or restrict competition is those laws should protect consumers. They are not there to protect competitors.”

“In the context of health care,” Gaynor said, “the focus should be on what’s best for patients. So scope of practice laws should be narrowly tailored to protect patients. This should be based on sound evidence. One important thing researchers can do is produce the best possible scientific evidence that addresses these issues so those who are in charge of making policy have the best available facts at hand with which to do that.

“The pandemic has brought about relaxations in licensing and scope of practice restrictions,” Gaynor noted. “And if these responses have been successful, then one important thing is they provide potentially really important scientific evidence.”

One of the conference’s panels, moderated by Penn Nursing Professor and LDI Senior Fellow Matthew McHugh, PhD, JD, MPH, RN, FAAN, focused on exploring the exact ways in which overly restrictive SOP regulations constrain the daily life and work of NPs and other health professions.

Tethering physician assistants

Retired physician assistant and Director of Advocacy and Government Relations for the Rhode Island Academy of Physician Assistants James Carney, PA, DFAAPA, cited tethering. “One of the major restrictions is the tethering of a physician assistant’s license to a specific physician, which is very restricting as far as PA mobility and being able to move from practice to practice or from setting to setting. Think of changing jobs to work for a hospital or large group practice or transitioning to a solo practice. Whenever a tethered PA decides to move or take a part-time job somewhere, they have to go back to the medical board and refile everything that goes along with their license.”

Carney noted the PA’s options for providing care are further truncated by distance restrictions that prohibit practice beyond a certain number of miles from the supervising physician. These kinds of restrictions have become even more tricky and troublesome in the new age of widespread telemedicine.

Dentistry’s rigid SOP restrictions have exacerbated disparities in access to care, according to panelist and University of Washington School of Dentistry Professor Donald Chi, DDS, PhD.

“Dental care access is a well-documented problem in the US,” said Chi. “You only have to look at the news to see the lines that form when there’s a free dental care clinic being held in a community. We actually have enough dentists; but the problem is they are not distributed evenly across communities, so some have no dentists. And this is really where dental therapy and dental therapists come in. The resistance to them largely comes from organized dentistry; it’s an issue of turf.”

Misinformation and scare tactics

“There’s been a lot of misinformation, and unfortunately, disinformation when it comes to the quality of care provided by dental therapists,” said Chi. “And much of this is based on scare tactics. Some say dental therapists won’t really make a difference in underserved communities. That is what motivated me and my research team to look at 10 years of Medicaid claims and electronic health record data from a particular part of Alaska called the YK Delta.” (In 2005, Alaska became the first state to permit dental therapists to practice under general supervision of a community dentist, without requiring the presence of the dentist.)

“Our research showed the Delta residents got more preventive care, more exams, cleaning, and fluoride treatments, the core services that prevent dental disease,” Chi said. “Both children and adults now get fewer teeth removed. Over time, we could see there are fewer emergency consults for dental problems.”

The Alaska investigation involved more than a dozen dental therapists working in an underserved population of about 25,000 and it was the first analysis of their long-term outcomes worldwide. “So we now have evidence that dental therapists are making a difference in underserved communities, and it’s a huge difference,” said Chi.

NPs and underserved communities

The most heavily publicized debates around the SOP issue over the last 60 years have been about nurse practitioners whose work is often focused on underserved communities that lack the most basic kinds of medical care. Panelist and LDI Senior Fellow Margo Brooks Carthon, PhD, RN, FAAN, is an NP and health services researcher in that field. She is also an Associate Professor at Penn’s School of Nursing, and a core faculty member at the Penn Center for Health Outcomes Policy Research.

“There are over two hundred thousand NPs in the United States working under varying degrees of scope of practice restrictions, depending on the states where they’re employed,” Carthon said. “These barriers have implications for population health as well as health equity.”

“Twenty-two states and the District of Columbia fully license NPs to practice independently. Others require career-long collaborative agreements with a supervising physician. Some require a physician to review a percentage of NP charts — ten percent every year in Alabama and Georgia; twenty percent every 30 days in Tennessee. NPs are often limited in the distance they can be from a physician and are required to jump through other hoops just to provide basic care.”

Historically marginalized individuals

“For historically marginalized individuals, including black and brown communities, low income communities, and residents living in medically underserved areas, a lack of access to primary care, preventive services, and mental health services is really at the core of many of the poor physical and health status disparities we see today,” she continued. “And the concern is that scope of practice restrictions contribute to that by impacting NPs’ ability to evaluate, diagnose or prescribe, or to work in the places they’re needed most.”

“We now know from a growing number of studies and reports that residents living in states with more restrictive nurse practitioner SOP regulations have, on average, less access to health care, and longer wait times. The supply of nurse practitioners in those states is also actually lower.”

“The best way to utilize NPs,” Carthon told the audience, “is let them work to the top of their license, let them do what they’re trained to do. We have to reduce this national patchwork of different scope of practice restrictions that leads to such variations. From an equity perspective, we need to work more in coalition building with one another. As someone who’s been an NP for 20 years, I think we’ve been having these turf wars for far too long, and patients get no benefit from that.”

Negative impact of practice restrictions

Another researcher focused on how SOP restrictions negatively affect underserved communities is panelist and health economist Bianca Frogner, PhD, Associate Professor in the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Washington School of Medicine and Director of the Center for Health Workforce Studies.

Frogner is one of seven directors of academic health workforce research centers around the country who recently pooled their SOP research insights in a New England Journal of Medicine article.

“The seven of us saw from our collective experience that the evidence has been growing that scope of practice is limiting access to care and unnecessarily so. Probably the greatest body of evidence has been around NP practice and how relaxing scope of practice has impacted access to care, especially in rural communities as well as other underserved communities. There are at least three very good systematic reviews pointing to many studies reaching similar conclusions around the benefits of relaxing scope of practice for nurse practitioners. And some of these systematic reviews have only come out in the last year or two. So we’re really starting to see that growing body of evidence emerging, in part because better data is now available.”

Doctoral level pharmacists

“Beyond nurse practitioners and physician assistants, debates are happening across other categories of health professionals, and it’s not always about one profession versus physicians,” Frogner pointed out. “For instance, I’ve studied pharmacists and the role they can play. Over the last decade or so, pharmacists have moved up to a doctoral level training program; they’re quite advanced and trained to provide clinical care. However, the reimbursement landscape prevents them from doing that. So it’s not always only about state laws, but also about what insurers are willing to reimburse.”

“I’ve also studied physical therapists,” Frogner continued. “All 50 states allow patients to have direct access to physical therapists as the first point of care; but despite that, there are still barriers. Insurers do not allow patients to go directly to physical therapists; they require a physician visit first.”

“It’s important to understand the turf wars we see happening across a spectrum of health professionals are not always about what’s happening at the state regulation level. They are also often about what insurers and employers are doing when it comes to practice limitations. A key point in all of this is that plenty of communities are not getting the care that they need. We need to elevate the conversation beyond just a ‘who is able to do what’ tug of war. The first thing we need to be doing is putting patients in the center of these discussions.”

Dramatic Veterans Admin SOP change

Penny Kaye Jensen, DNP, APRN, Director for APRN Practice for the Department of Veterans Affairs, briefed the audience how the VA has expanded SOP for its APRNs. Beginning with a policy change in 2016, the VA health system recently completed the final implementation of a national policy that eliminates previous SOP limitations for nurse practitioners, clinical nurse specialists, and certified nurse midwives. All 6,000 of them working in the VA’s 1,200 medical centers and outpatient clinics in 50 states are now practicing to the full extent of their expertise in a system that provides health care to nine million veterans.

In part, the three-year delay in full implementation of this VA change was due to ferocious opposition lobbying by physician advocacy groups and an effort by several state governments to block the SOP change at VA facilities within their own borders. The VA used its legal federal supremacy to overcome those state efforts.

Panelist Carthon noted the unprecedented size and importance of this development within the context of the SOP debate.

Large-scale example

“The VA change provides a large-scale example of how to nationalize scope of practice and reduce the state patchworks that lead to such variations and the other issues we’ve been discussing,” said Carthon.

“Think of it,” Carthon continued. “In the face of unacceptable appointment wait times and restrained access to care that put our nation’s veterans are at risk, we’ve witnessed the determination required to reduce or relax SOP restrictions. And so the question as we leave this seminar is, will we develop the same determination for the good of historically marginalized and underserved communities? I think we have an opportunity to do so now.”