Blog Post

Sugary Drinks – You’ve Been Warned

What policymakers can learn from research

While a tax on sugary drinks is grabbing the headlines in Philadelphia, several cities and states are exploring other interventions to curb the consumption of sugary drinks, and hopefully reap health benefits. One such proposal is to put warning labels on sugary drinks, or on the advertising for them, calling out adverse health effects, particularly obesity, diabetes and tooth decay. A San Francisco ordinance, which requires publicly displayed advertising for sugary drinks to devote 20 percent of the ad to a warning label, was scheduled to take effect this summer but is on hold pending legal challenges.

While we can’t yet evaluate the real-world impact of sugary drinks warning labels, recent work by Christina Roberto and colleagues tests the extent to which exposure to warning labels on beverages might influence beliefs and purchasing choices of adolescents and parents. In separate studies, the researchers use online surveys to assess the hypothetical purchasing choices of teens and parents after exposure to a warning label or a calorie count label. In both studies, seeing a warning label made participants less likely to purchase a sugary drink, for themselves (adolescents) or their children (parents).

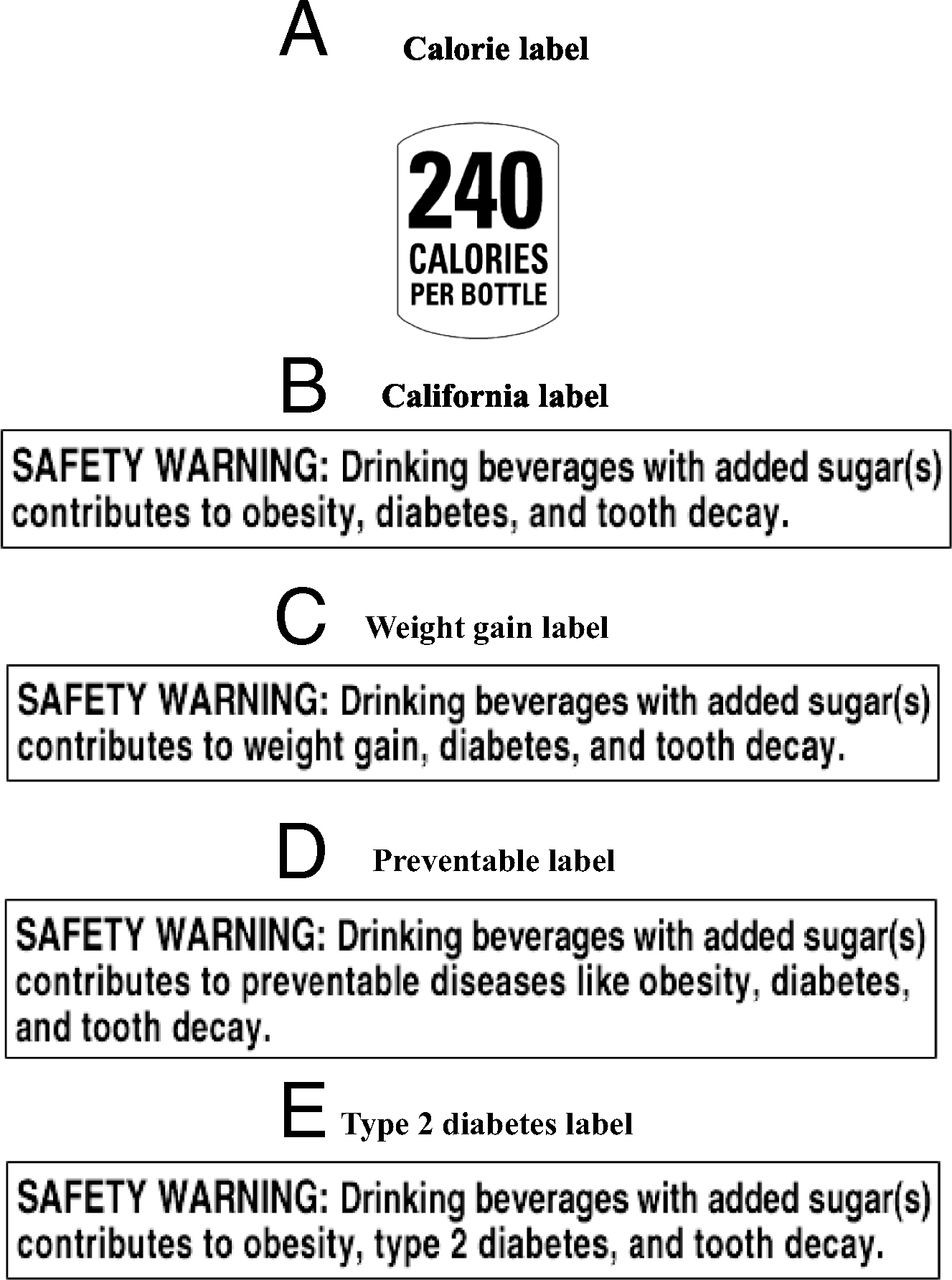

Participants were randomly assigned to one of six conditions – no label, a calorie label, or one of four versions of a warning label, one of which is text from proposed California legislation, as below:

Some key findings about teens:

- 77% of participants who didn’t see a warning label said they would purchase a sugary drink.

- This figure went down to 61-69% with exposure to a warning label, with varying impact of the different labels.

- Calorie labels increased adolescents’ estimates of the calories in sugary drinks, but had no impact on purchasing behavior.

- Warning labels reduced the perception that sugary drinks contribute to a healthy life.

- Warning labels had little impact, either positively or negatively, on judgments of non-labeled beverages.

Some key findings about parents’ purchasing choices for their children:

- 60% of participants who didn’t see a warning label said they would purchase a sugary drink for their children.

- This figure went down to 40% with exposure to a warning label, with no consistent differences among different versions of the warning labels.

- Calorie labels produced no significant differences in purchasing behavior.

- Participants who were shown a warning label believed that sugary drinks were less healthy for their child and were less likely to intend to purchase sugary drinks.

What can we make of these findings? These studies show warning labels to be effective in reducing purchasing propensity and changing beliefs about sugary drinks. But three-quarters of adolescents who did not see a warning label said they would purchase a sugary drink, and even if warning labels produced a 16% reduction in that figure, that’s still a lot of sugary beverages being consumed. Although the starting point is lower, the effect is similar for the study of parental preference. Warning labels are a step in the right direction, but most likely will not have a measurable impact on health outcomes on their own. They may have a role, however, as part of a larger set of policies designed to support healthy eating.

Another key point is the lack of effect of the calorie label on purchasing behavior. The authors suggest that future research could examine whether the diminished impact of calorie labels, in relation to warning labels, is due to the safety and health information included in the warning labels, greater novelty of warning labels, or difficulty in interpreting calorie labels. They suggest that additional contextual information, such as a clearly communicated threshold for high calorie content, could strengthen the impact of calorie labels.

Proponents of warning labels cast them as a health and justice issue, allowing consumers to make an informed choice. Policymakers considering the adoption of warning labels on sugary drinks can learn a lot from these recent studies. With future implementation we’ll be able to see if warning labels’ theoretical potential to reduce the consumption of sugary drinks plays out in reality.