Population Health | Substance Use Disorder

News

The Rising Power of Administrative Data for HSR Scientists

How Penn's AISP Quietly Pioneered a Revolution in Data Use

Penn School of Social Policy & Practice Professor and LDI Senior Fellow Dennis Culhane, PhD, is one of those leading a national revolution in the way government administrative data is used by researchers.

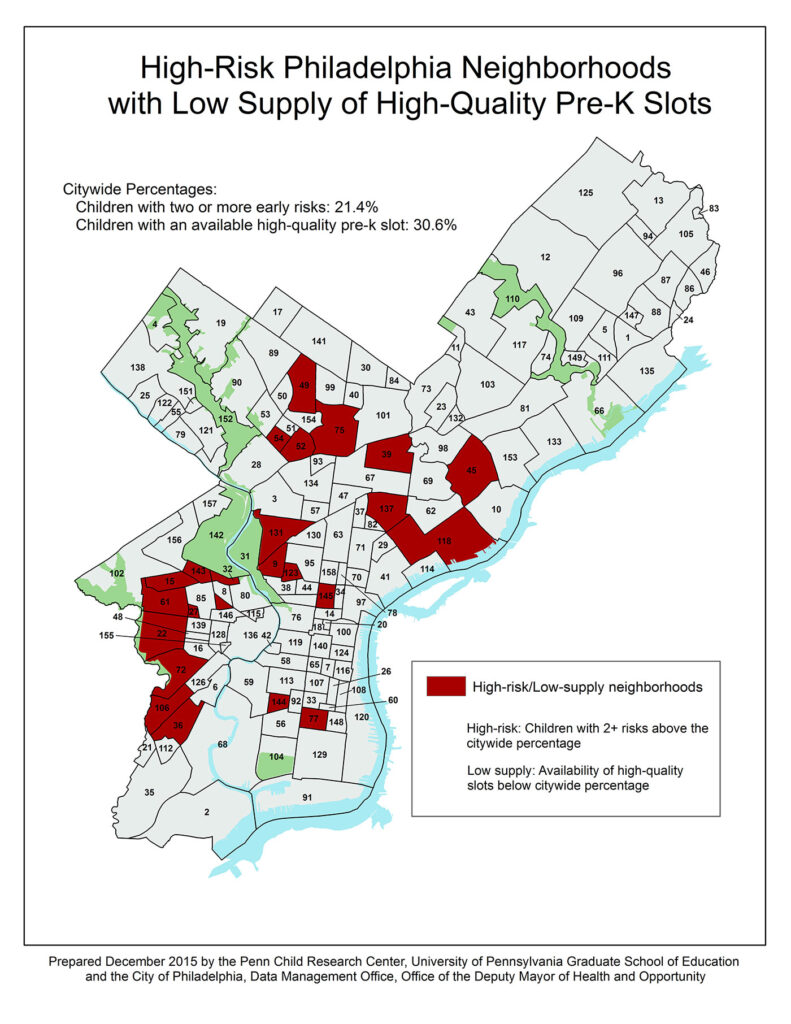

In 2016, after City Council approved a soda tax to fund the operation of pre-kindergarten educational programs throughout Philadelphia, the city had to decide where this funding would be targeted. It turned to the University of Pennsylvania’s Actionable Intelligence for Social Policy Center (AISP) to create a data model mapping key early childhood risk exposure across the neighborhoods.

Using prenatal and premature birth records, lead exposure test results, abuse or neglect investigations, out-of-home placements, homelessness episodes as a young child, and other sources of government administrative data, AISP compiled a score for every child in the city who experienced two or more of these risks.

“The work was done by my colleague John Fantuzzo,” said Dennis Culhane, who, along with Fantuzzo, is Co-Founder and Co-Director of the AISP. “AISP overlaid Philadelphia with a map of where the kids with the highest needs were and where the largest gaps between needs and access to pre-K slots were.”

Culhane, PhD, is a professor of Social Policy at Penn’s School of Social Policy & Practice; of Psychology at the Perelman School of Medicine; and of Policy Research and Evaluation at the Graduate School of Education. He is also an LDI Senior Fellow. Fantuzzo, PhD, is a Professor of Human Relations and Director of the Penn Child Research Center at the Graduate School of Education. Headquartered in the School of Social Policy & Practice, the AISP office has seven staff and faculty members and three student workers.

Integrated Data Systems (IDS)

Culhane and Fantuzzo have been involved in Integrated Data Systems (IDS) work for over 30 years, making them leading national experts in the aggregation and use of government administrative databases to inform and support federal, state, county and municipal policymakers. During the last decade, with funding from the MacArthur and Annie E. Casey Foundations, AISP has created a national network of integrated administrative data systems.

Administrative data — the information routinely collected by government agencies and other service providers — has a long history of being viewed skeptically by research scientists and grant funders.

That began to change in the 1980s in parallel with the evolution of ever-more powerful and sophisticated computer technologies adopted by government offices to hold and handle their daily tsunamis of incoming data. This includes files collected by agencies involved in health & vital statistics, education, child welfare, juvenile and adult justice, homeless shelters, employment and earnings, workforce development, behavioral health, assisted housing, and other areas.

Pioneering a new field

In that decade, the scientific research and development work that pioneered the process of standardizing, aggregating and analyzing these kinds of information in IDS was done in South Carolina. Leading this was Peter Bailey, MPH, a statistician from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. He joined the Office of Research and Statistics of the South Carolina State Budget and Control Board in 1978 and spent 35 years refining the IDS concept and inspiring younger colleagues like Culhane.

Culhane, the former Director of Research at the National Center for Homelessness Among Veterans for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, initially began integrating administrative data in his studies of homelessness.

“I made a career of linking homeless records with all these other systems to look at the mutual impact of both homelessness on those systems and those systems’ impact on homelessness,” Culhane said. “That was 20 years of connecting homeless shelter records to datasets of prisons, Medicaid utilization, emergency room use, births, deaths, school attendance, earnings, workforce participation, child welfare involvement, foster care and juvenile justice.”

The accidental expert

“The end result,” he continued, “was that I sort of accidentally became an expert in the legal, data security and ethical issues associated with accessing and using these records.”

Under Federal privacy laws — FERPA that covers educational records, HIPAA for health records, and the Privacy Act that covers other government records — it is permissible to reuse administrative data for research, evaluation and auditing purposes. But even then, there were gray areas AISP had to help clarify over the years.

There was not really an ethical framework around just these datasets, so we applied an IRB ‘human subjects’ framework. The main principles are autonomy, beneficence and justice.

with citation

Dennis Culhane

“There was not really an ethical framework around just these datasets,” Culhane said. “So, we applied an IRB ‘human subjects’ framework. The main principles are autonomy, beneficence and justice. Autonomy means protecting the privacy of individual records. Beneficence means the research projects have to be focused on the public good. It has to be contributing to the well being of the population, including the people whose data are being used. Justice means it should be addressing issues of inequity and disadvantage; it should not be amplifying those.”

IDS databases operate much like the highly secure Medicare/Medicaid files that are used by health services researchers under tight security precautions and restrictions. When researchers receive a requested dataset, it is anonymized.

Culhane’s early homelessness research with these records systems garnered major attention with its new insights into the financial implications of those government services interconnections. “It was particularly fruitful because you can monetize a lot of these services to actually see the cost of homelessness to these other individual systems,” Culhane explained.

Building Philadelphia’s IDS

In 1999, he teamed with Fantuzzo and Penn Professor of Psychiatry and LDI Senior Fellow Trevor Hadley, PhD, to build an IDS for the City of Philadelphia.

In 2000, in another project that was, at the time, the largest linked administrative study ever undertaken, the researchers set out to track 10,000 homeless individuals in two groups experiencing both homelessness and mental illness across eight different agency data systems in New York City. “In the end, we were able to show that the average individual in this group was costing the city $40,500 a year in service engagements,” Culhane said.

Five thousand of those 10,000 had been placed in permanent housing units with support services and the researchers found the cost of their engagements with city agencies went down 35%.

“So, instead of $40,000 a year, they were using $24,000 a year and the difference of $16,000 was essentially the cost of the housing, so it was break-even from a public investment standpoint,” Culhane said.

MacArthur Foundation grants

The findings made headlines across the country and drew the attention of the MacArthur Foundation, the country’s 12th-largest private philanthropic organization. It saw this new kind of IDS analysis as a potentially potent tool for social welfare research and government policymaking. In 2008, the Foundation provided the funding that launched Penn’s

Actionable Intelligence for Social Policy initiative (AISP).

Goals of that ten years of funding were to establish standards and practices for the field; create a national network of scientists and government managers engaged in the work to facilitate sharing of information; foster the creation of new IDS systems in other states, counties, and cites across the country; and work with federal agencies to develop standardized guidelines for such data aggregation and use.

IDS research projects are becoming critically important because they can identify the extent of a particular problem and its interrelationships with all these other agencies. Nine of our sites have been doing opiate-related projects just to get their hands around where the opiate crisis is being felt most and see where the potential points of intervention are.

with citation

Dennis Culhane

A key part of the organization’s work has been the AISP Learning Community Initiative that provides training and technical assistance to state and local governments as they work toward creating the infrastructure for their own IDS operations. Participants have included California, Oregon, Utah, Colorado, Iowa, Delaware, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and North Carolina. The states currently in AISP training are Vermont, Connecticut, Georgia and Kentucky.

Opioid crisis data

“IDS research projects are becoming critically important because they can identify the extent of a particular problem and its interrelationships with all these other agencies,” said Culhane. “Nine of our sites have been doing opiate-related projects just to get their hands around where the opiate crisis is being felt most and see where the potential points of intervention are. You have the EMT data, ER data, homelessness, jail, prison and medical examiner data. For instance, it’s been shown that people who have been clean and sober during their time in prison often overdose within the first few weeks of their release. That’s a very useful insight.”

While most state governments recognize the potential of having an IDS, the process of creating one across sprawling bureaucracies is very complex. Culhane points to one state that engaged AISP for support after struggling with 200-some data sharing agreements and an average timeframe of 10 months for negotiating each agreement.

“We help a state like that implement a governance process called an E-MOU — an Enterprise Memorandum of Understanding — that all agency secretaries have to sign, committing their organizations to sharing data and putting it in a data linkage center and standardizing the whole process, ” Culhane said.

Legal tangles

When asked what the biggest barrier has been to convincing states to create IDS over the last decade, Culhane answered quickly and decisively with a single word: “lawyers.”

“Lawyers in some of the individual agencies can be very risk averse and have historically just said ‘no’ to any access request because they can’t get in trouble that way,” he said. “That’s changed a lot in the last five years and there is a growing sense of ‘why not use the data, given how it can improve programs and create public good?’ We see a switch happening in senior state leadership — governors and secretaries saying this really makes sense — an AISP can help them manage their internal legal challenges. We have lawyers on our own team who are experts in this.”

Culhane also acknowledged that along with state officials, researchers and their institutions are increasingly recognizing the value of administrative data.

“For many years, administrative data were not respected by federal funding agencies or journals who viewed such data as too dirty, or limited, or otherwise not of sufficient scientific quality,” said Culhane. “And there certainly are data quality issues but it’s also possible to ‘wrangle’ the data and identify the quality variables, it just takes time and capacity that is in short supply within some agencies. Usually, the things that are audited for financial purposes are really good. While a lot of what is in these original datasets may not be useful, our experience is that you can usually identify the variables that are of sufficient quality for analysis purposes.”

What is clear, Culhane said, is that rapidly advancing computer technologies continue to make it possible to deal with administrative data in evermore sophisticated ways and provide academic researchers with new kinds of resource supports.

HSR research resource

“Imagine that researchers can both get a specific dataset and bring their own dataset,” Culhane said. “So, if they’re studying a group of 500 patients and then want to get the last five-year history of the services they used in Philadelphia. Or, the researcher did a study ten years ago and wants to see what impact their intervention had on earnings, or employment or survival. IDS has the ability to do the long-term look-backs — and forwards — like this.”

“We know that many LDI-affiliated faculty researchers are using administrative data now and they are also sharing the pain of the often difficult process involved in getting that data,” Culhane said. “We appreciate that; one of our goals is to reduce the friction associated with accessing these data and thinking through all the different dimensions and concerns so that in the not-too-distant future, there will be much greater access and ease of access to conduct research of great importance to the public.”