Health Equity

News

The Ties Between Structural Racism, Voting Rights, and Health Equity

LDI Virtual Seminar Explores the Political Determinants of Health

The often non-obvious connections and entangled synergies of the U.S. voting process, health disparities, and structural racism were the subjects of the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics’ first virtual seminar of 2021.

“On the heels of the recent election, it’s important that we not lose sight of the issues of voting and representation as we consider how to address health inequities in our nation,” said LDI Director of Policy David Grande, MD, MPA, as he opened the program.

Moderated by Atheendar Venkataramani, MD, PhD, LDI Senior Fellow and Director of the Perelman School of Medicine’s Opportunity for Health Lab, the event featured three other top experts in the fields of political science, voting rights and health disparities. They were Nicole Austin-Hillery, JD, Executive Director of the U.S. Program at Human Rights Watch and a renowned voting rights expert; Javier Rodríguez, PhD, Co-Director of the Inequality and Political Research Center at Claremont Graduate University; and Daniel Dawes, JD, Executive Director of the Satcher Health Leadership Institute at the Morehouse School of Medicine.

The seminar was co-hosted with Bold Solutions, a University of Pennsylvania initiative aimed at addressing the effects of interpersonal, structural, and institutional racism on health; and co-sponsored by the Opportunity for Health Lab.

Mortality disparity

Panelist Rodríguez discussed his article and findings published in the journal of American Politics Research (APR) about connections between racial mortality disparity rates and U.S. voting outcomes.

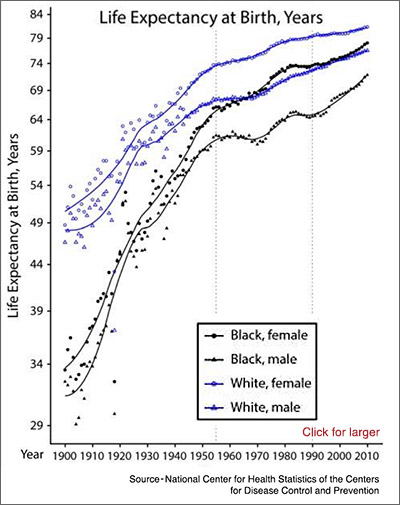

Throughout the history of modern medicine, African Americans have had much lower life expectancy rates than white Americans. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) explains, “Disparities in the leading causes of deaths for Blacks compared with whites are pronounced by early and middle adulthood, especially deaths from homicide and chronic conditions such as heart disease and diabetes. In addition, Blacks have the highest death rate and shorter survival rate for all cancers combined compared with whites.” While there has been a narrowing of the life expectancy rate in recent decades, the current COVID-19 pandemic is so drastically affecting African Americans, it is again widening Black/white life expectancy gap.

“I’ve looked at racial disparities in mortality and the effect that has on the electorate to see how many votes have been removed from that electorate just by the excess mortality of the African American community,” said Rodríguez.

Removed from the electorate

“One of the things that I noticed is that policy is central to the social determinants of health. The government is at the center of all the distribution and production of how social determinants of health are distributed and accessed by racial and poor communities,” Rodríguez said. “Mortality rates are quite sensitive to who gets what and by how much. When I look at particular groups like African Americans and the poor, I ask how many of these people would have been removed from the electorate if they had had mortality rates similar to whites. Let me give you one example to quantify the size of the problem.”

“In our paper, we put together 35 years of death certificates from 1970 to 2004,” he continued. “We saw that when you put together excess mortality and excess mass incarceration, you had about four million people removed in excess from the electorate. The findings were unexpectedly enormous when you compared Black Americans that were removed to all races combined. It implies that excess mortality is removing a bigger chunk of the Black American electorate.”

“For example, more than 20 percent of all the African-American population growth never happened because of the dynamics in which people are dying off from the electorate in middle age,” Rodríguez said. “That is precisely when they are supposed to be participating the most. We know participation in politics increases gradually with age and stabilizes in the older years, but the lion’s share of the electorate is comprised of people in the middle age group.”

Balance of power

“So what we have is a removal of the African American population precisely when they were supposed to be participating the most,” Rodríguez pointed out. “That has implications for the balance of power between the parties because the African American community has overwhelmingly voted for the Democratic party. So we also estimated how many different elections would likely have shifted for the Democratic candidate had all these people been alive. We found that during that 35-year period, seven senatorial elections and 11 gubernatorial elections would have shifted to the Democratic candidate. That would have put, for example, Bill Clinton in his second term in control of the Senate and House, but that never happened precisely because of these issues.”

“Today,” Rodríguez said, “as all elections become increasingly competitive, you can imagine that very small numbers in different states define who gets in power. The effects are just enormous. When we look at how this generalizes to the poor, we see 57% of the electorate differences in participation throughout the population are due to health differences related to mortality.”

Struck by the comments, moderator Venkataramani noted, “That is such a stark portrayal of something I had never thought about — that we focus so much on the voters who are alive and can vote, but what about the voters who didn’t have the chance to go through the process of registering and voting because they’re not alive?”

Political determinants of health

Panelist Dawes spoke about the political mechanisms essential to either maintaining the current status quo or re-inventing the government approach to issues like health care.

“Most everyone understands what the social determinants of health are and why they matter,” said Dawes. “But we have to look beyond those at the political determinants of health. I’m referring to the three upstream factors — government, policy, and voting — that impact our health. It’s important to realize that for every social determinant of health, there was some preceding legislative, legal, regulatory or other policy decision that resulted in that social determinant. Those are the political determinants of health.”

Voting, government, and policy are all three parts of the same continuum or process that can either address health inequities or further entrench them.

Daniel Dawes, JD

“For example, think about the Owners Loan Corporation Act of 1933 that intentionally redlined America,” said Dawes. “This is a systematic process of distributing resources. Think about the appropriations process. Think about the time that we’re living in right now during the COVID pandemic and issues like distributing testing kits or vaccines and making sure those distributions are accomplished in an equitable manner.”

Systematic process

“This systematic process administers power, such as redistricting, gerrymandering, et cetera, and operates in ways that mutually reinforce one another to either hinder or advance health equity. Now that you know what these determinants — these political decisions — are and how they can negatively impact health, you can begin to understand how unrepresentative or unresponsive government and policy can have such a negative impact on health,” Dawes said.

“Voting, government, and policy are all three parts of the same continuum or process that can either address health inequities or further entrench them,” he concluded. “So, by engaging the government, holding it accountable with voting and pushing for more equitable policies, we can leverage the political determinants of health for the greater good.

The voting part of this effort has become more difficult for communities like African Americans as a result of the 2013 U.S. Supreme Court decision that struck down crucial elements of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that had, for 48 years, stopped the most egregiously racist voter suppression tactics of state and county governments.

2013 SCOTUS ruling

“Before 2013,” explained Austin-Hillery, “the ways in which voting laws were overseen by the federal government was that jurisdictions and states that had a history of discrimination in voting had to submit any changes to their voting laws to the federal government before they could institute those changes. It only applied to states and jurisdictions and localities that had a history of voter discrimination. The 2013 SCOTUS ruling said those ‘preclearance’ regulations were outdated and it doesn’t seem like we need those anymore. So we’re going to do away with them. And that basically opened the floodgates.”

We’ve turned from being a country where laws protect the voters from voting discrimination, to one where the power has moved into the hands of activists.

Nicole Austin-Hillery, JD

In writing the 2013 dissenting opinion for the four Justices who disagreed with the Court’s five conservatives, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg argued, “throwing out preclearance when it has worked, and is continuing to work, to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”

The “rainstorm” in this case, according to Austin-Hillery, is that efforts to impose various voter suppression policies and practices have exploded in the years since 2013. “We saw myriad states introduce legislation dealing with implementation of voter ID laws, doing away with same-day voting, doing away with early voting, and other changes that had a disparate impact on Black and brown and poor communities,” she said.

State legislative actions

In addition, at present, there are more than 100 bills pending designed to make voting more difficult in various state legislatures.

“At the same time,” said Austin-Hillery, “an amazing grassroots effort has been underway to try and fight back against the fact that we no longer have the protection of 1965 law. And you saw that grassroots effort play itself out rather beautifully in this recently past election of 2020. So, now we’ve turned from being a country where laws protect the voters from voting discrimination, to one where the power has moved into the hands of activists. While that did work wonderfully in the 2020 election, the problem is it shouldn’t just be the role of activists and community organizers to protect the right to vote.”

As he brought the session to a close, Moderator Venkataramani noted “Right now in the United States, we’re in a new political moment. And I’m curious what that means to our panelists. If you had to list the top thing you’d want to change or you want to do, what would that be?”

Austin-Hillery answered the question in two words: “economic inequality.”

Economic inequality

“If I had a magic wand,” she continued, “the first thing I would do is ensure that we had economic equality across the board in this country. It relates to what access you have to health care and at what level; it relates to whether you are in a community where you have access to voting and whether you’re getting the kinds of educational materials you need about voting. It impacts housing, which we know is interrelated with the hospitals and health care systems you have access to.”

“Until we really try to take the issues around economic inequality head on and close those gaps, all these issues we’ve talked about today are going to remain extremely difficult. I want to see the Biden administration and every administration thereafter work to do a better job to ensure that we have more economic parity in this country. That is what should be at the heart of any democracy: leveling the playing field for everyone. Ensuring economic justice and access is a huge part of that.”

‘We know what to do’

Answering the same question, panelist Rodríguez said “disparities in health have been here for a very long time. We have known for decades what needs to be done, but the problems are entrenched. The question is why? And the answer is the government. Politics is the problem and also the answer. We know what to do. We’re not doing it. The real question is how can we change politics in a way that gets it done?”