HIV is Not a Crime: The Case for Ending HIV Criminalization

Outdated Laws Target Black and Queer Lives in Over 30 States, Fueling a Deadly Disease

Brief

Stimulants are playing a prominent role in the current U.S. overdose crisis. As stimulant use continues to mount, the need for evidence-based treatment grows more urgent. This brief highlights contingency management, the most effective treatment for stimulant use disorder, and reviews the current barriers to its widespread use along with practice and policy strategies for increasing implementation.

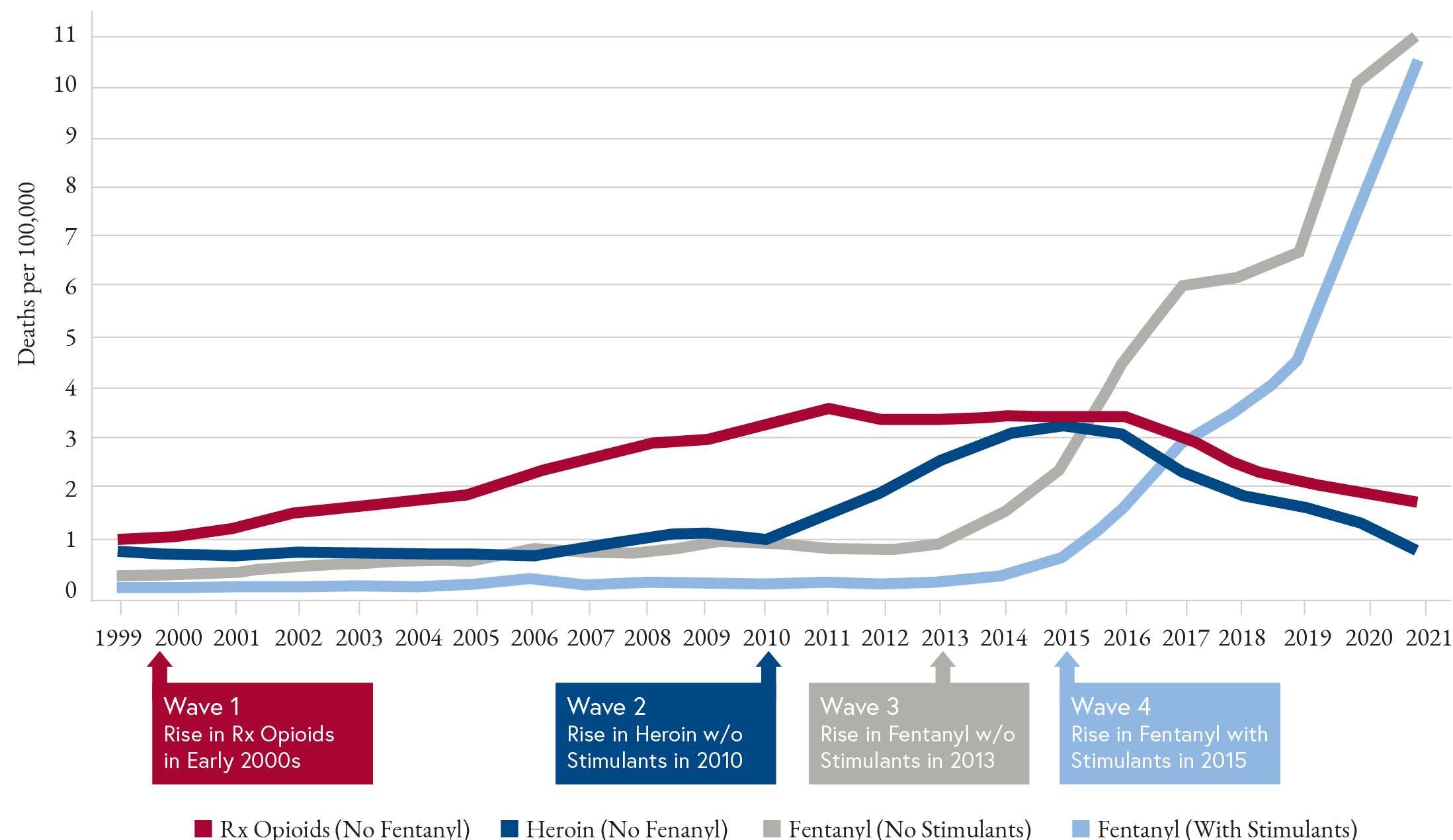

Stimulants are involved in a substantial and growing percentage of the more than 100,000 overdose deaths in the United States each year.1 Methamphetamine and cocaine are increasingly present in overdoses involving fentanyl (Figure 1)—fueling what has been called the “fourth wave” of the opioid overdose crisis.2 Unlike opioid use disorder, there are no FDA-approved medications to treat stimulant use disorder. However, a behavioral intervention called contingency management (CM) has been proven effective in managing a variety of substance use disorders, including tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, and stimulants. Also known as motivational incentives, CM reinforces positive recovery behaviors, including abstinence and retention in treatment programs, with financial rewards. Despite the considerable evidence for its efficacy, CM is underutilized in the treatment of stimulant use disorders, prompting recent commentators to call it “the most effective, evidence-based treatment you’ve never used.”3 This brief reviews available evidence, implementation examples, and promising strategies for increasing CM use in treating stimulant use disorder.

Based on psychological principles of operant conditioning, CM uses financial incentives to reinforce healthy behaviors. In substance use treatment, for example, an individual can receive a reward for providing a drug-free urine sample or for attending a treatment appointment. The reward can be structured as a voucher or gift card with a set value, or as a prize with a chance for rewards of varying values, usually from $1 to $100.

Decades of evidence4 show that CM is the most effective treatment available for stimulant use disorder, with significant impacts5 on abstinence during treatment and adherence to treatment plans. These effects on abstinence can persist at least one year after treatment. CM is about twice as effective as other behavioral treatments, including cognitive-behavioral therapy, counseling, or motivational interviewing. CM is effective alone or in combination with other evidence-based behavioral therapies, with some evidence of increased benefit when combined with a community-reinforcement approach (CRA). Voucher-based and prize-based rewards have been found to be equally effective, with longer treatment periods (for example, 16 to 24 weeks) associated with greater effectiveness.6 One influential group of experts recently suggested that incentives at the level of $100-$200 (USD 2022) per month are most effective and have the greatest likelihood of producing benefits that exceed the costs beginning in the first year.7

Despite the strength of this evidence, CM approaches have not been widely implemented by health systems and treatment programs. One notable exception is the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), which has implemented CM for the treatment of stimulant use disorder and cannabis use disorder across its health system. More than 100 VA medical centers offer a CM program that involves twice- weekly prize-based rewards for negative urine screens over the course of 12 weeks.3 The average value of incentives over the 12 weeks is about $200 per veteran, with coupons redeemable for merchandise at any Veterans Canteen Service retail store, cafeteria, or coffee shop. More than 6,300 veterans have received contingency management treatment since 2011. Among the nearly 82,000 urine samples submitted, more than 90% tested negative for the target substance (most commonly stimulants).8

In 2021, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) approved California as the first state to cover CM for stimulant use disorder through a Medicaid demonstration waiver. In June 2023, CMS also approved Washington, and since then, Delaware, Montana, and West Virginia have submitted similar requests for Medicaid coverage of CM for stimulant use disorder.

The California program, known as Medi-Cal Recovery Incentives, involves counties covering 88% of California’s Medicaid population and runs through March 2024.9 Eligible Medi-Cal members participate in a structured 24-week outpatient program, followed by at least six months of additional recovery support services. Participants meet with a trained CM coordinator twice weekly for the first 12 weeks of the program, and then weekly for weeks 13 to 24 to complete a drug test. Participants receive a small gift card each time they test negative for stimulants and can earn up to $599 per year in incentives.

More widespread implementation of CM is hindered by a number of practical, policy, and attitudinal barriers. These barriers include concerns about potential violation of federal fraud and abuse laws; limited funding and reimbursement opportunities, program restrictions on use of CM; and a lack of provider knowledge along with negative attitudes and stigma toward CM.3

Federal rules prohibiting kickbacks, physician self-referrals, and patient inducements may deter some providers from participating in CM programs. But a 2020 Office of Inspector General (OIG) report clarified that CM programs would not run afoul of these rules, as long as safeguards are in place to prevent fraud and abuse, paying for referrals, or marketing to patients to select a specific provider.10 In response, a policy group has recommended “guardrails” that can minimize the risk of violating these federal statutes.7

Funding for CM programs have been limited by a common misperception that federal guidelines prohibit CM program incentives above $75 in aggregate per person per year. The OIG has clarified that all cash and cash-equivalent payments, including in-kind incentives above $75, would need to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.10 Despite this ruling, the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) maintains budget restrictions for its grant recipients that limit rewards in CM programs to $15 for each reward and $75 per client per budget period,11 amounts well below what has been shown to be effective in research and in large-scale implementation at the VA. Even when programs can offer rewards greater than $75, they often cap the value at $599 per year to prevent the incentives from becoming taxable income, which could threaten clients’ eligibility for public benefits. A policy group has called on the Internal Revenue Service to recognize incentives within a CM program as part of a health care intervention, and consequently, consider them to be medical treatment and not taxable income.5

Finally, provider stigma and misperceptions hinder more widespread adoption of CM. Some clinicians object to CM on the grounds that it undermines internal motivation, fails to address underlying issues for the individual, costs too much, or is too hard to implement. Other health professionals cite the possibility of trading the reward or gift for illicit drugs as a reason to mistrust CM. Some policymakers question the ethics of contingency management, and whether such patients “deserve” a reward.4 Some opponents consider CM to be “bribery” and hesitate to reward people for staying off drugs. Recently, these attitudes about the use of CM with patients have been reframed as stigma, and provider training efforts are underway to promote better acceptance of CM among health professionals and the public.4

A new report to Congress by the HHS Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) presents practical and policy opportunities that could overcome barriers to widespread implementation of CM for stimulant use disorders.4 Opportunities outlined by the ASPE include:

While the evidence base for CM as a treatment for stimulant use disorders is strong, many questions remain about implementing CM within the current environment of increasing overdose deaths and polysubstance use. Research is needed to address the following questions:

This Issue Brief was prepared in advance of the Penn LDI/CHERISH Virtual Conference – Incentivizing Recovery: Payment, Policy, and Implementation of Contingency Management on January 19th, 2024.

Research Contribution by Lyric Harris

Outdated Laws Target Black and Queer Lives in Over 30 States, Fueling a Deadly Disease

Selected for Current and Future Research in the Science of Amputee Care

Penn LDI Seminar Details How Administrative Barriers, Subsidy Rollbacks, and Work Requirements Will Block Life-Saving Care

Top Experts Warn of Devastating Impact on Community Safety Efforts

A Gathering of a Health Services Research Community Currently Under Siege

1,000+ Detail the Latest Health Services Research Findings and Insights