Blog Post

Modernizing Medicare Funding for Nurse Education

Aiken and colleagues present case for new consortium model

With policies rooted in the 1960s, it’s time to change how Medicare pays for nurse education. In a New England Journal of Medicine Perspective, LDI Senior Fellow Linda Aiken and colleagues present a compelling case for funding a new consortium model that trains nurse practitioners (NPs) in the community settings where they are a crucial source of primary care.

Bolstered by the success of the five-state, $200 million Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Graduate Nursing Education (GNE) demonstration, Aiken and colleagues point out that permanent funding for the model could help meet national health workforce needs, by coordinating training resources across communities and institutions. The demonstration, which paid Medicare providers to participate as training sites and preceptors for advanced practice nurses, resulted in a substantial increase in new graduates, mostly NPs going into primary care.

Penn School of Nursing and the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania partnered in the largest consortium, serving as the designated regional hub for a network that included all health systems and hospitals in the area, more than 600 community-based providers, and all nine local university nursing schools. Graduate nursing students continued to pay tuition, and received no stipend. Medicare reimbursed medical practices for precepting these trainees – important training for which no other funding source exists.

Crucially, the GNE model provides a cost-effective way to train primary care providers. Depending on the methodology, the cost to Medicare of training a new advance practice nurse ranged from $28,000 to $57,000, compared to the cost of training a primary care physician of about $158,000 a year for multiple years. But GNE funds do not compete with graduate medical education funds. Medicare currently funds nurse education according to an outdated formula, with prelicensure hospital diploma programs receiving the bulk of the funding.

This funding policy is showing its age. Hospitals may receive payments to offset the clinical costs associated with university degree programs, only if they were reimbursed by Medicare for nurse training costs in 1989 — before most advanced practice nursing programs existed. This means that Medicare funding goes to a small and dwindling number of hospital diploma programs that train less than five percent of registered nurses. Moreover, the graduates of diploma programs do not meet the educational qualifications recommended by the National Academy of Medicine for the nation’s future nurse workforce – a minimum of a baccalaureate degree in nursing.

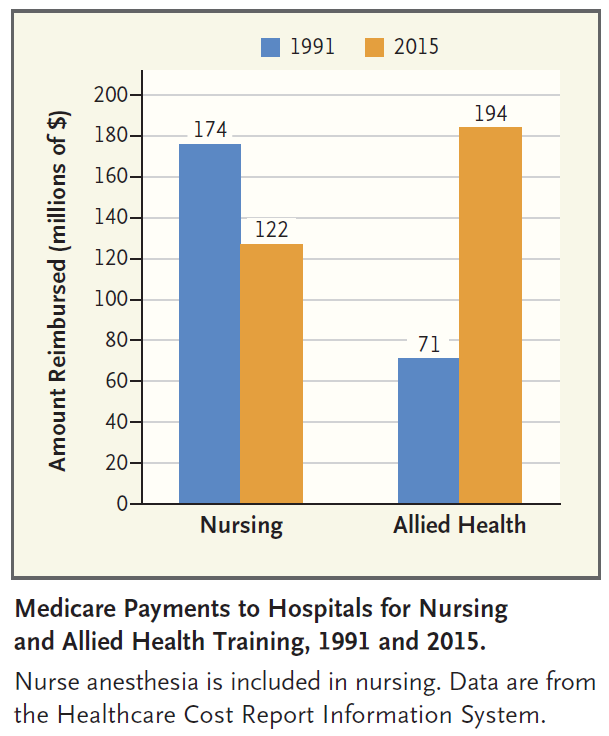

And the total amount of Medicare funding is shrinking, both in absolute terms as well as in terms of nursing’s share of non-physician training funds. As shown below, Aiken and colleagues estimate that Medicare funding for nurse training decreased between 1991 and 2015, from $174 million to $122 million.

Also, states that have historically been home to diploma nursing schools are receiving a disproportionate share of these funds. In 2015, hospitals in six states (PA, IL, OH, NY, VA, MO) received 53 percent of Medicare’s nurse training funds, while only two hospitals west of the Rocky Mountains received any Medicare funding for nurse training.

As Aiken and colleagues note, “The GNE Demonstration shows how Medicare could achieve greater value for its investments in nurse training while contributing to the development of a workforce that can better deliver the care that Medicare beneficiaries want and need.” Much of the cost of funding the consortium model could be covered by phasing out low-value investments in prelicensure RN programs that no longer match the workforce needs of today and tomorrow.