Blog Post

Medicare, Medicaid and the Leonard Davis Institute – Intertwined Legacies

Celebrating 50 years

Fifty years ago, on July 30, 1965, President Lyndon Johnson signed Medicare and Medicaid into law. Over the next two years, more than 29 million people gained health coverage through these programs. By 1967, as Alice Rivlin recalls, economists were sounding an alarm about rising Medicare costs and reporting to the President that projected growth would be unsustainable. Concern about the growing federal costs in Medicaid led Congress to limit Medicaid eligibility to the “medically needy” with incomes no greater than 133.3% of the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) eligibility level.

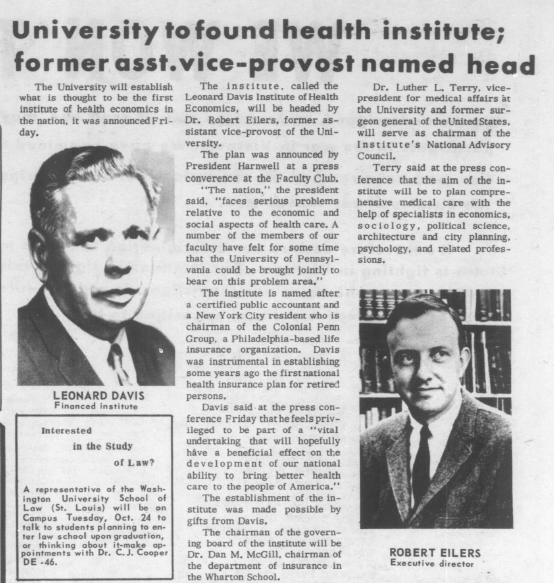

It is no accident of history that LDI, the first institute of health economics in the United States, was founded at Penn in 1967, in the wake of the passage of Medicare and Medicaid. As these landmark programs celebrate their 50th birthday, we went back to see what our founders had to say about Medicaid and Medicare. Those conversations shaped our institute and still inspire our dedication to research that leads to affordable, high-quality health care that is accessible to all.

“We do not know whether six percent of the nation’s GNP is too much or too little to spend on health care…we do not know what impact various levels of expenditure might have on mortality, morbidity, and productivity.”

So said Robert Eilers, one of LDI’s founders (and our first Executive Director). Although the level of expenditure might seem quaint, the question is still central to the nation and to the research we do at LDI.

Another LDI founder, William Kissick, often recalled his days as one of two physicians in the office of the Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) as the Medicare legislation was being drafted in 1964 and 1965 (purportedly finalized over a weekend sitting at HEW Secretary Wilbur Cohen’s breakfast table). He described the program as a “Herculean political achievement” that replicated the predominant insurance model of the day:

“What Medicare did, basically, was use tax dollars to provide open-ended funding of Blue Cross and Blue Shield coverage of the 10 percent of the population over 65 years of age.”

Medicare and Medicaid were the first national, though not universal, health insurance programs. Luther Terry, another of LDI’s founders and a former Surgeon General of the United States, noted in 1967 that the programs were connecting people to needed medical care but straining existing budgets:

“The demand on our nation’s health resources today is no less than overwhelming. Recent government legislation including Medicare, Medicaid…are making qualified medical care available to large segments of the population to whom it was formerly unavailable because of cost.”

It’s striking how much this statement still resonates today with the passage of the Affordable Care Act five years ago.

What would Eilers, Kissick, and Terry say now that our country spends more than 17% of its GDP on health care? Fifty years later, would they have anticipated that Medicare and Medicaid would account for 20% and 15% of national health care spending, respectively?

Actually, yes. Eilers, early on, worried about the effect of Medicare on costs. In a 1970 presentation to the American Sociological Association, he said:

“(T)he fact that the consumer incurs little, or at least less, personal expense in obtaining insured services tends to encourage increases in unit costs….The Medicare Program provides partial evidence of this fact, inasmuch as over one third of the dollars expended since the program was instituted in 1966 have been paid for increased prices rather than for increased services.”

At a National Laboratory of Medicine meeting in 1991, Kissick, tongue only slightly in cheek, warned that the cost growth was unsustainable:

“In 1965…the United States spent 6 percent of gross national product on health, 6 percent on education. In 1990, the United States spent 12 percent of gross national product on health, 6 percent on education. The forecast for the year 2000 is that we will spend between 15 and 18 percent of gross national product on health and medical care, and I am certain 6 percent on education. If that is true, early in the 21st century the United States will have a very well-medicated illiterate labor force busily selling french fries to each other under golden arches. [General laughter] At which time Japan, Inc., and the European Economic Community will dominate world markets and our economic well being.”

Kissick seems to have been wrong about Japan and the European community, but the projections on health care and education were close: today health care is at 17.4% and education at 7.4%.

But our founders did not just fixate on the big problems of the day; they oriented our work to look for solutions. We can hear echoes of our founders’ wisdom and insight in the ACA, as well as in the Medicare and Medicaid programs.

Today’s experiments with shared savings and shared risk in Medicare? Here’s Eilers in 1971:

“The means of assuring accountability appear to lie in the program requirement, imposed directly or indirectly, that physicians and hospitals benefit financially if efficient use is made of services by consumers who utilize them as the main source of care and, alternately, that physicians and hospitals be adversely affected financially if efficient use is not made of services.”

The surprising growth and robustness of Medicare Advantage? It has its roots in a team of three consultants, including Eilers, who as a special assistant to President Nixon in 1970 promoted the idea of controlling costs in Medicare through private prepaid plans rechristened as “health maintenance organizations.” There was a long and winding road from HMO demonstrations in the 1970s to Medicare Part C in 1982, to the Medicare Advantage plans we know today, but the idea of managed care is still very much with us. I suspect that Eilers, Terry and Kissick would have a lot to say about the new generation of managed care we call Accountable Care Organizations. In fine tradition, our current Senior Fellows Mark Pauly and Lawton Burns have taken up that mantle.

So to Medicare and Medicaid, happy birthday. Our founders and our fates are deeply intertwined. We look forward to the next 50 years together, as the American health care system continues its journey through what Kissick called the “Iron Triangle”: the delicate and optimal balance among cost, quality, and access to health care.