Health Equity | Improving Care for Older Adults

News

Already in Fiscal Crisis, Rural Hospitals Face COVID-19

LDI Virtual Seminar Eyes Coronavirus' Spread Through America's Hinterlands

As COVID-19 continues its accelerating spread from high-density cities into rural counties, the University of Pennsylvania’s Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics (LDI) focused its eighth virtual seminar on rural populations’ unique pandemic-related vulnerabilities.

Entitled “Rural Health in America During COVID-19,” the session brought together top rural health experts and was moderated by LDI Senior Fellow Joanna Hart, MD, MSHP, an Assistant Professor of Medicine at the Perelman School of Medicine and head of LDI’s newly-formed Rural Health and Policy Research Working Group.

Very limited resources

“The 20% of the U.S. population that lives in rural areas consists of generally older individuals with more chronic conditions who are more likely to be under- or uninsured,” said Hart. “They are more likely to be experiencing poverty and have limited access to health care. Even before COVID-19, rural hospitals faced significant financial challenges and operational limitations. The volume and acuity of COVID-19 cases in those areas will quickly overwhelm the very limited resources of many rural communities.”

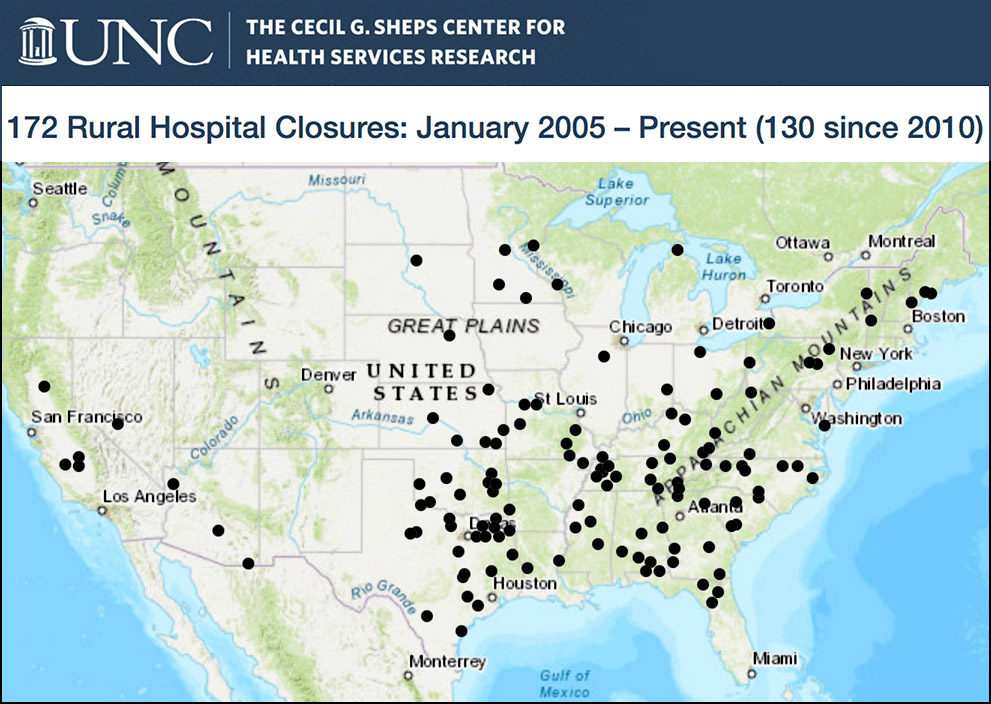

The plight of rural hospitals has been a subject of much concern and debate in recent years; since 2005, 172 of these facilities have closed, according to the North Carolina Rural Health Research Program run by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research. Last year, the number of closings set an annual record as 15 more rural hospitals went under, leaving their surrounding communities without the kind of care only hospitals can provide.

“Rural hospitals tend to have lower days of cash on hand, and higher rates of negative operating margins,” said panelist Lisa Davis, MHA, Director of the Pennsylvania Office of Rural Health and Outreach. “So they’ve been struggling traditionally. Then, a pandemic like COVID-19 comes along and they need to essentially pivot on a dime and close down service lines that tend to bring in revenues such as surgery, outpatient services, emergency departments. They don’t have the economies of scale to be able to rely on other sources of revenue.”

“Even though the numbers are smaller, just a couple of COVID-19 cases can really overwhelm a hospital that has only 25 beds and does not have a lot of workforce resources,” said panelist Cara James, PhD, President of Grantmakers in Health and former Director of the CMS Office of Minority Health, “A couple of cases can push a community over the edge.”

‘Intractable issue’

Rural communities that have lost their hospital, often lack even local primary care providers. “Workforce recruitment and retention has been an intractable issue since I’ve been working in rural health,” said Davis. “So, being able to attract and retain primary care and specialty care providers is a real concern.”

“An issue the pandemic threat magnifies, related to workforce in rural health systems, is that elsewhere across the country we see how front-line health care providers have become infected and succumbed to the disease,” said James. “If that happens in a rural community it can have a large effect.”

Other panelists noted that the rural hospitals’ fiscal difficulties also make them likely to be less well stocked with the personal protective gear or other special equipment essential for safely treating patients infected with coronavirus.

“One of my friends’ hospital has a single ventilator,” said panelist Mark Holmes, PhD, Professor and Director of UNC’s Sheps Center for Health Services Research.

Sicker population

Another important factor in rural COVID risk is that rural hospitals deal with a sicker population than urban hospitals. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), rates for the five leading causes of death in the United States — heart disease, cancer, unintentional injury (including vehicle accidents and opioid overdoses), chronic lower respiratory disease, and stroke — are higher in rural communities. So are rates of smoking and obestity.

“COVID-19 impacts individuals with co-morbid and chronic disease conditions more,” said panelist Karen Murphy, PhD, RN, Geisinger Health System Executive Vice President and Chief Innovation Officer. “So not only do rural hospitals have the burden of being challenged with a smaller or shorter ‘bench,’ but they also treat patients that are more vulnerable to COVID-19 because of their preexisting conditions.”

Over the last two months, the outbreaks sweeping through big cities have been radiating out into vast swaths of the rural hinterlands where COVID-19 hotspots are now flaring up. For instance, a Brookings Institution analysis tracked how the outbreak in New Orleans has spread in all directions into rural areas of Alabama, Mississippi and Arkansas. The same thing is happening in parts of Pennsylvania.

Hunting camps and vacation homes

“What the hospital CEOs tell us,” said Davis, “is that when they drive to work, they go by hunting camps and vacation homes in the Poconos where people from urban areas have migrated and brought whatever germs they have with them. They’re not isolating in those hunting camps or vacation homes, and as they go out shopping in the community, they may not be wearing masks.”

A Washington Post analysis found that of the country’s 25 rural counties with the highest per capita COVID-19 case rates, 20 have large meatpacking plants or prisons. The virus first took hold in those facilities and was then taken out into the surrounding community by commuting workers and back-and-forth service traffic.

Another potential vulnerability for spreading coronavirus in rural communities is the fact that intergenerational households are more common there than in metropolitan areas.

“Given the role we know of prolonged exposure in interior settings, that’s a big risk, especially as we reach the fall and the schools start reopening,” said Holmes. “School-age children may be less affected by COVID, but they are a vector for the grandparents they live with who are at high risk.”

Systematically transfer cases?

In North Carolina, Holmes said, the plan is that rural hospitals won’t be exclusively responsible for managing all of the community care in situations of high infection case loads. “There are fewer acute beds and fewer ICU beds per capita in rural areas,” he said. “The question is how that demand is managed. Each state and region is going to have to consider that. Do you want to systematically transfer high-acuity cases to larger facilities elsewhere that have greater capacity?”

Holmes also said North Carolina is taking a recently closed rural hospital and positioning it as a surge facility should the need arise.

One set of Pennsylvania rural hospitals doing better than most are the 13 within the state’s unique Rural Health Model developed in 2017 in partnership with the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI). It is the only program of its kind in the country, and is based on the Global Budget System originally developed by the State of Maryland.

Pa. Rural Health Model

The Pennsylvania Rural Health Model transfers hospitals out of fee-for-service mode into a global payment mode covered by private and public insurers. Instead of being paid for volume of treatments, each hospital gets a preset amount to provide services to its community.

“In rural communities where hospital services are declining, fee-for-service has really contributed to their financially challenged status,” said Murphy, who was the architect of the new system’s implementation. “Rural Health Model hospitals that are on a global budget don’t have to worry about what volume they have because their reimbursement scheme continues. When we were writing and developing the model, we also considered extraordinary circumstances, like a pandemic. So, even that’s figured in the global budget.”

To deal with the pandemic, Geisinger Health System’s rural hospitals quickly shifted to digital strategies like remote monitoring and virtual visits to maximize the number of patients treated at home. “We’ve been luckier than most in terms of broadband availability in the rural communities we serve,” said Murphy. “I think we’ve all learned that connecting virtually is something we want to build on coming out of the pandemic because it has been so particularly helpful in our communities.”

Digital care disparities

While it seems clear that, on a national scale, telemedicine will be a big winner coming out the other end of the COVID-19 crisis, the panel voiced multiple concerns about what that means for the digital haves and have-nots across rural America.

“The telemedicine discussion reminds me of what many rural communities actually face,” said James. “For instance, think of what the the Navajo Nation faces. Last year, in September, part of the Navajo Nation just got electricity. So, forget about 5G when we talk about broadband; there are still some rural people waiting for 1G.”

“We know there is a great opening up of telemedicine, but not all communities are able to participate in it equally,” James continued. “We need to make sure that telemedicine doesn’t worsen disparities.”

A broadband New Deal

“Many people are now writing about how this pandemic is an ‘inflection point’ for the country that allows us all to think about how we can build a better mousetrap,” said James. “Looking back at the Great Depression, we see the New Deal it produced went on to electrify rural communities. I think we need a second New Deal to get broadband across rural communities not just to support telemedicine, but education and employment as well. This pandemic experience shows that we have to think big and think bold and in ways our government doesn’t often do from one legislative session to another.”