Population Health

News

Penn Nursing’s Mobile App Targets HPV Vaccination Gap

LDI Senior Fellow Anne Teitelman's Latest mHealth Research Project

The opening paragraph of University of Pennsylvania nurse-scientist Anne Teitelman‘s latest published paper gives voice to a personal frustration more than a decade old: “More than 90% of human papillomavirus (HPV)-related cancers could be prevented by widespread uptake of the HPV vaccine, yet vaccine use in the United States falls short of public health goals.”

The new paper in JMIR Nursing details the development and usability study of Vaccipack, Teitelman’s latest smartphone app designed to encourage uptake and completion of the HPV vaccine’s multiple-dose regimen for children. And, indeed, the paper documents a pressing need. While some 72% of adolescents aged 13 to 17 have received their first HPV vaccine dose, only 54% have completed the required multiple-dose regimen. This compares to the 89% or greater vaccine completion rate for tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis, and meningococcus vaccines.

Providers have to take the lead in providing strong recommendations for the vaccine. Many may not realize the pivotal role they play. If they say to patients something like, ‘Well, if you’re a little hesitant, maybe you want to wait and see,’ that is not helpful.

Anne Teitelman

Penn School of Nursing Associate Professor Teitelman, PhD, FNP-BC, FAANP, FAAN, heads a team of researchers and digital developers who have helped establish Penn Nursing as a center for mHealth technology. Vaccipack is her third smartphone app; she is currently working on a fourth.

Vaccipack, like Teitelman’s other apps, is a research project; there is currently no marketing company or commercialization plan involved. “We’ve made it freely available on the Apple App Store and Google’s Play Store,” she said. “We’re trying to create the best evidence for an intervention, and we’re in the first phases of understanding usability, feasibility, and acceptability. The next phase would be to look at outcomes of the intervention itself: does it actually increase the uptake of the HPV vaccine? If that is successful, then we could actively advocate for its widespread use.”

Focused on the health and wellbeing of minority adolescents and young women in minority communities, Teitelman’s 35-year research career intersected early with the smartphone technologies that drove a communications revolution led by the young. In low-income, underserved communities smartphones quickly became highly popular and particularly important as economical tools for crossing the digital divide.

Real-world context of users’ lives

“All my app work has been patient-facing rather than provider-facing because I am trying to get at hard-to-reach populations,” said Teitelman. “I’ve been committed to grounding these digital tools’ content in the real-world context of users’ lives through qualitative research and user input.”

In 2013, Everyhealthier Women, her first smartphone app focusing on female cancer prevention won a national award from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Her second and third apps — NowIKnow.mobi and Vaccipack.org — also focus on the HPV that causes a majority of those gynecological cancers.

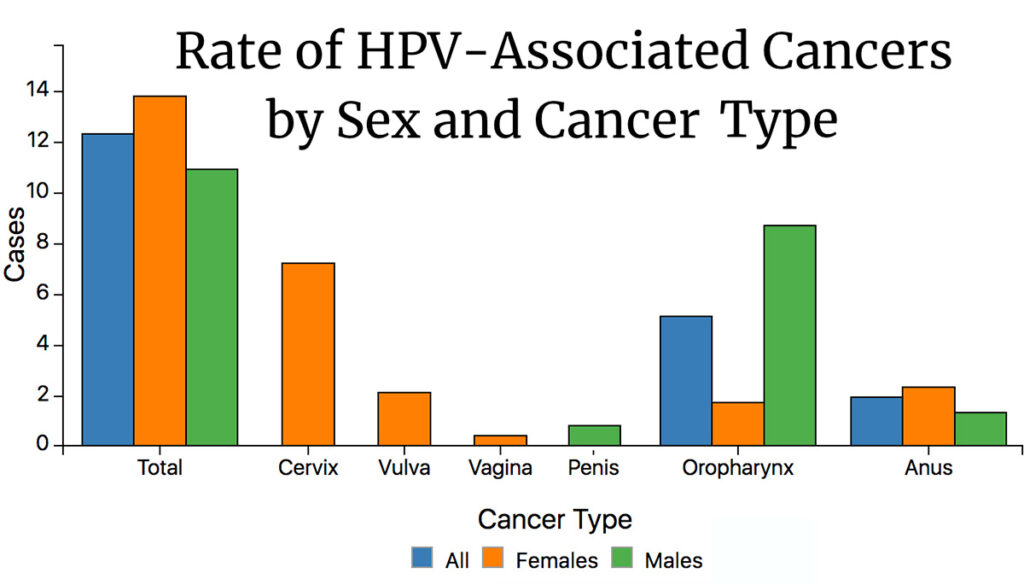

The most common sexually transmitted infection in the U.S., HPV is responsible for 90% of cervical and anal cancers, 70% of vaginal and vulvar cancers, 60% of penile cancers, and is believed to be linked to up to 70% of mouth and throat cancers. Since the introduction of the first HPV vaccine in 2006, there has been a significant decline in HPV-related cancers and pre-cancerous lesions across the country.

Despite this breakthrough pharmacological success, both the initial vaccination rates and the “completion” HPV vaccination rates have lagged far behind those of other vaccines. Adolescents up to 14 need two shots of HPV vaccine, 6 to 12 months apart; people from 14 to 26 need three shots in that same period to achieve full immunological protection.

Racial disparities

In 2012, as researchers began to assess the first six years of HPV vaccine use, it was clear the drug itself was effective but, as in most other areas of U.S. health care, there were racial and ethnic disparities associated with its use. Minority women were less likely to complete the vaccine regimen even as they had higher rates of cervical cancer than white women.

Teitelman was one of the researchers struck by these disparities. As a teen growing up in Chicago in the 1970s, she was a volunteer worker at a free women’s health clinic. As a nursing student at Yale in the 1980s, she focused her research on the health, health care, and reduction of sexual risk among of marginalized adolescent girls. And as a PhD student at the University of Michigan, she focused her dissertation on the population of girls who came to clinic with rapid-repeat pregnancies and STIs. The paper’s findings were that the young patients received limited information from family and school that left them unprepared for basic prevention or for relationships, especially those involving coercion and abuse.

As a senior nurse scientist at Penn, Teitelman has continued the study of adolescent lifestyles and decision making. Both areas underwent sweeping changes in the wake of the Apple iPhone release in 2007 and the Apple App Store launched 16 months later. She was in the first wave of academics to fully appreciate how transformational these smartphone-based software programs were.

Deficits of social support

“Working in the middle of a clinic, we could see how an instant information portal as close as the phone in your pocket offered a good way to reach a community of patients,” said Teitelman. “As a nurse practitioner, there was so much information to provide patients, but visits were getting shorter and shorter. That was another reason an app channel seemed a potentially effective way to augment what providers could provide patients who otherwise experienced such deficits of support within their social context.”

Teitelman stepped into the actual app designing and building arena in 2012 when she led a Penn Nursing team in the development of the Everhealthier Women app that in 2013 won the $85,000 top prize in the national HHS “Reducing Cancer Among Women of Color” app challenge. The contest required creation of an app that “engages and empowers women in underserved and minority communities to improve the prevention and treatment of breast cancer and gynecological cancers.”

Teitelman’s Everhealthier Women app linked users to information about cancer prevention, screening services and locations, including support groups and care services. The smartphone app received a large boost when it was featured in O, The Oprah Winfrey Magazine.

HPV vaccine among African American women

Logically growing out of this work — given that most gynecological cancers are caused by HPV infections — was a new research project aimed at both developing evidence-based methods for designing health care-related apps and developing one aimed at increased HPV vaccine uptake among young African American women. The problem targeted by Teitelman’s new NowIKnow app was HPV vaccine regimen completion among 18-26-year-olds. Their demographic had the lowest rate of getting the final two of the three injections required to complete the HPV vaccination process over a six-month period.

“We already had HPV racial disparities in how Black women were disproportionally affected by cervical cancer, so if they were not getting the full vaccination, that would actually widen the disparity gap,” said Teitelman. “NowIKnow was focused on completion of the three doses.”

She explains the latest Vaccipack app is different from NowIKnow in substantial ways. “It aims to promote the uptake of the initial HPV dose and then the follow-up second dose required for all 11-14-year-olds, both boys and girls,” she said. “Another big difference is that NowIKnow was aimed at an 18-26 age group of young adult women who were already sexually active. That app’s contents were racier and had a more mature street flavor aimed at real-world behaviors and perceptions. Vaccipack, on the other hand, is primarily aimed at parents of 11-14-year-olds as well as the children themselves.”

Adolescents named the app ‘Vaccipack’

Two advisory groups — one of parents and one of adolescents — participated in the iterative design of Vaccipack. The name of the app came from the adolescent group. “They thought it was a cool idea to have their vaccine records in their own kind of digital ‘backpack,’ like they owned them,” explained Teitelman.

Vaccipack includes an introductory video, vaccine-tracking files, a discussion forum that enables parents and their adolescents to communicate with others making similar vaccine decisions, and a series of 26 short (two-to-four paragraph) stories. The story links can also be pushed out in text messages to users as reminders in the interim between the first and second vaccine doses. Written at a middle-school reading level, the stories are constructed to address the beliefs, assumptions and HPV vaccine-related concerns of parents as documented in previous scientific literature.

The idea of Vaccipack is that parents would take their 11 to 14-year-old child into a provider’s waiting room, scan a barcode, download the app to their phone, and watch the informational video before seeing the provider. The provider can then talk with a parent and teen who already have basic information. If they decide to get the vaccination, they can immediately enter the related data into the app. When they go home, the app provides additional information and support, as well as ongoing reminders leading up to the appointment for the second dose of the vaccine.

Vaccipack and other vaccines

Although it heavily emphasizes the HPV vaccine, Vaccipack is also designed to hold information for the bundle of other standard adolescent vaccines. However, it is not configured for information about COVID-19 vaccines.

Teitelman was asked what insights from her app research might be useful for those working with the national COVID-19 effort. She noted that a COVID-19 app could be very useful for not only documenting what vaccine had been received and when, but might also allow travelers, for example, to quickly show airport personnel that they have been vaccinated.

She also noted that COVID-19 vaccination efforts face hesitancy issues similar to those of HPV vaccination efforts.

“Providers have to take the lead in providing strong recommendations for the vaccine,” she said. “Many may not realize the pivotal role they play. And if they say to patients something like, ‘Well, if you’re a little hesitant, maybe you want to wait and see what happens,’ that is not helpful.”

“One thing we didn’t expect was that the adolescents in the Vaccipack study said the person whose app recommendation they most trusted — over that of parents or teachers or friends — was their provider,” Teitelman said. “Providers really have to get on board and really recommend the vaccine.”