News

Penn’s Nationally Renowned Accidental Health Economist

A Look Back at Mark Pauly's Years as LDI Executive Director

A nationally-renowned health economist, University of Pennsylvania Wharton School Professor Mark Pauly served for five years in the 1980s as the Executive Director of Penn’s Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics (LDI). Here, he stands outside the castle-like main entrance door to LDI’s headquarters building at the center of the Penn campus.

Much like the history of the University of Pennsylvania’s Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics (LDI), the career of health economist Mark Pauly begins at the dawn of the Medicare age and continues through the current implementation of the Affordable Care Act.

During that half-century, Pauly, a Wharton School Professor of Health Care Management and former Executive Director of LDI, rose to national prominence with his seminal works and insights on health insurance design — achievements that belie the fact that his entry into the field of health economics was a serendipitous accident.

As part of its 50th Anniversary celebration in 2017, LDI is profiling the lives and works of its seven former Executive Directors. Pauly was LDI’s fifth chief from 1984 to 1989 when Ronald Reagan was President and four of health care’s biggest issues were annual costs that had just burst into GDP double digits, the rapid expansion of the HMO model, and the separate thorny questions of how to effectively alter the way hospitals and physicians were paid.

The Early Years

In 1966 Mark Pauly was a Research Associate and PhD student approaching his dissertation year at the University of Virginia’s Thomas Jefferson Center for Political Economy. Initially, he focused on the thesis idea of designing the economic framework for a government-funded voucher system for public education.

Meanwhile, beyond the bucolic Virginia campus on the edge of the Blue Ridge Mountains, the world of U.S. health care was in the throes of epochal change. Nineteen million people had signed up for the first year of Medicare coverage in 1966. The political rancor swirling around the implementation of Medicare and Medicaid was intense. Many states made no effort to establish Medicaid programs. The president of the American Medical Association denounced both Medicare and Medicaid as attacks on “capitalism and the American way of life” and called on physicians to circumvent the programs or work for their repeal. Meanwhile, the initial economic assumptions used to fund the launch of Medicare and Medicaid proved faulty as the programs burned through their first 12-month budgets in half that time.

This last event underscored what regulatory agencies, health care delivery systems and insurance executives were quickly coming to recognize as a major national deficiency: the lack of economists trained and experienced in the unique complexities of government health care financing on a vast scale. In fact, the academic field of health economics barely existed.

Stanford University’s Kenneth Arrow had only published the first “exploratory and tentative study” of how standard economic principles might be applied to medical care in 1963. One of the only other significant pieces of literature available on the subject was the 1965 book, “The Economics of Health,” by Johns Hopkins’ Herbert Klarman. It argued that although the economics of health care had become one “of the most important and sensitive areas of the entire economy,” most U.S. economists were paying little attention to it “because the special characteristics of health and medical services mark them as exceptions to the economic propositions that explain the behavior of the market.”

Focused on his studies as well as his new wife, 25-year-old student Pauly was only vaguely aware and not much interested in these outside happenings until his mentor, James M. Buchanan, PhD, explained that the law creating Medicare also provided funds for academic health economics studies. He suggested that Pauly switch his thesis focus from education to health care economics and apply for a federal grant.

“Broadly speaking, I was interested in government and public policy,” Pauly remembers. “But the thing that drew me to health care economics was the money. I wish I could be more noble, but that was the reason. I got the grant and the rest is history.”

And, indeed, it’s been quite a history.

“Looking back over the last 50 years, it is nearly impossible to overstate Mark Pauly’s influence on health economics and health policy,” said Thomas McGuire, Professor of Health Economics in the Harvard Medical School’s Department of Health Care Policy.

“For instance, the essence of his thinking and writings can be seen in many of the provisions of the Affordable Care Act including the law’s individual mandate, subsidies for the poor, competitive structure and the Cadillac tax,” McGuire said. “Pauly’s earlier framing of the moral-hazard-as-demand-response model remains the primary way economists and most policymakers think about the connection between health finance and health care utilization. No paper has been more influential in the way health economics is thought about and studied.”

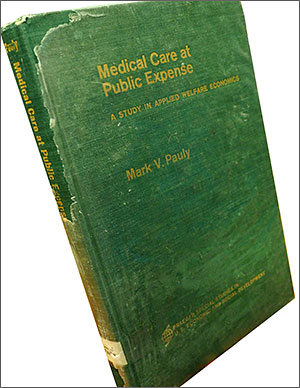

In 1967, hunched over a battered U.S. Army surplus desk in a dingy campus PhD bullpen room, the young Pauly scrawled his ideas on yellow legal pads to produce “Medical Care at Public Expense: a Study in Applied Welfare Economics.” The dissertation outlined the overarching economic concepts for a “means-tested premiums for means-tested coverage” system of tax-subsidized health insurance for low-income people.

Meanwhile that same year, three hundred miles to the north in Philadelphia, events driven by the country’s new focus on government-funded health care systems were establishing what would become a major platform in Pauly’s future career.

The Wharton School

Established in 1881 as the country’s first business school, Penn’s Wharton School has inherently focused on recognizing and responding to the constant change and emerging new challenges of U.S. commerce. In 1966, Wharton Dean Willis Winn was approached by Philadelphia-based insurance executive and philanthropist Leonard Davis who was one of many in the health insurance industry grappling with the dramatic changes in the health care financing system resulting from the rollout of the revolutionary Medicare and Medicaid programs.

Davis, who headed the Colonial Penn Group insurance company, was concerned about the lack of academic research facilities capable of producing the evidence needed to support the insurance industry during a time of such sweeping disruption and broad new opportunities in the national health care market. His view was that academia’s traditional single-discipline research practices were no longer sufficient; that new levels of complexity and cost demanded deeper, broader and more practically-oriented scientific insights in the business of health care financing and delivery.

The end result of those Philadelphia discussions between Davis and Winn was a flow of funding that established Penn’s new Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics (LDI) and purchased a central campus building to house the new center and its staff. LDI was the first academic center of its kind designed to foster and facilitate multidisciplinary research in the business-side of medical care.

Initially, LDI was exclusively focused on faculty-conducted projects that brought together researchers from the medical and business schools. Minutes from the 1968 annual meeting of LDI’s National Advisory Council detail the progress of that first round of research projects focused on reimbursement methods for Medicare and Medicaid nursing home care, dentistry services, and the potential structure, legalities and logistics of new sorts of community care centers.

Over the next 17 years, LDI became nationally known for its pioneering efforts to bridge the gap between the two previously disparate academic kingdoms of medicine and business administration. It created an executive education program that brought together health care industry leaders from across the country with Penn’s top academic health services researchers. And it launched new kinds of undergraduate and MBA curricula that wove together both the clinical and financial sides of medical care.

During these same 17 years, Mark Pauly went on to become a Professor and nationally renowned health economist at Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill. In less than three years after writing his PhD thesis, he had been called to serve as a consultant to the White House Office of Management and the Budget for federal health care insurance plans. It was the first of several federal consulting positions he would hold, including the Congressional Budget Office, Office of the Health and Human Services Secretary, and the Physician Payment Review Commission that advises Congress.

1983: Pauly Arrives at Penn

In the final years of his term as LDI’s third executive director for 1978 to 1983, Wharton Professor William Pierskalla, PhD, received approval from the Wharton faculty to create a new department. An undergraduate and MBA health care management curriculum existed before he arrived but there still wasn’t an overarching department with the authority to hire faculty members and the expand the program in other ways.

One of Pierskalla’s first acts after creating what was then known as Wharton’s “Health Care Systems Department” was to open negotiations to recruit its second faculty member after himself: Northwestern University Professor Mark Pauly.

“By that time in his career,” said Peirskalla, who is now retired and living in Florida, “Pauly had become one of a handful of the leading health economists. He was a perfect fit for my plan at LDI and Wharton to find and hire the best people in the country.”

Pauly remembers the fast moving action of that transition. “I was taken advantage of,” he recalled with a laugh. “My original plan was to come to Penn as a researcher. But no sooner had I agreed to that, and even before I arrived at Penn, Bill (Pierskalla) called to say, ‘by the way, I’ve just agreed to be Deputy Dean’. Then, soon after I had arrived, Dan McGill, the very courtly Chair of the LDI Governing Board, stopped by to ask, ‘Would you be Director of LDI and take over the Chair of the Health Care Systems Department?’ I hadn’t planned for that at all, but I figured I can do anything once, and so, I said yes.”

Unique Cooperative Spirit

Pauly was impressed how LDI — a standalone institute separate from Penn’s schools — had garnered an unusual kind of cross-campus support that had long eluded similar centers in other universities.

“When I took over as executive director,” he recalled. “John Eisenberg, then head of Penn’s Department of General Medicine told me ‘Let’s agree that we don’t care whose business administrator administers the grants’. This was a totally different philosophy from what I’d seen at Northwestern and Harvard and Stanford and other medical schools where faculty members are more dedicated to having property rights and being more grasping. I think LDI has been able to succeed so well over the years because of the unique ethos of Penn’s culture that embodies a cooperation spirit you don’t find elsewhere.”

According to Arnold Rosoff, Wharton Professor Emeritus and member of the LDI Executive Board back then, Senior Fellows didn’t know what to expect from the newly-arrived Pauly because they viewed him as the first economist as well as the first “pure” academic to head LDI.

Long-time LDI Senior Fellow Sankey Williams, MD, a Professor at both Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine and Wharton, remembers that Pauly quickly made his mark as an “intellectual, academic powerhouse full of ideas given to pursuing the highest quality of research and inspiring people to do things that they couldn’t otherwise do.”

‘Skunk at the Picnic’

Famed for his ability to mix hard numbers and folksy humor in his classroom lectures and podium appearances, Pauly notes that a health economist’s inevitable job is to be “the skunk at the picnic” by documenting how health policy projects are likely to cost far more than anticipated.

For instance, when he moved into his new LDI office in 1984, he joined a building full of faculty members who were generally gung-ho about health maintenance organizations. The rapid rise, expansion and ultimate decline of HMOs was one of that era’s major trends.

But Pauly wasn’t a fan of the HMO ballyhoo and predicted HMOs would initially reduce short-term costs by about 15% but have no impact on the continuing rise of overall health care costs. His predictions came true.

“I had all these reporters calling me and asking, ‘Why did the magic of HMOs go away?’ And I’d say the magic didn’t go away. Things are 15% cheaper than they otherwise would be but that’s as far as the magic goes,” Pauly said.

“For the most part, HMOs were directed at reducing the quantity of old services and hospitalizations,” he continued. “There was nothing in them to produce a permanent reduction in the rate of growth. Once you moved everyone into managed care, you got a reduction because you’re moving to 85% of what you had before. After that, you returned to the same health care cost trajectory driven mostly by new technology.”

Pauly believes today’s policymakers are doing something similar with the Affordable Care Act’s Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), which he characterized as “HMOs for Democrats.”

“In terms of the ACO organizational structure,” he said, “we’re repeating the mistakes of the HMO era. So far, the savings with ACOs is, like, 1% but that’s not enough to be worth the trouble.”

Grants and Collaborations

The three issues Pauly focused on as he settled in as LDI chief in 1984 were the departing Pierskalla’s mandate to create a PhD program within the Health Care Systems Department, his own vision to more effectively organize and expand LDI Senior Fellows’ research efforts, and the funding needed to support both objectives.

“I could see that Leonard Davis’ money wouldn’t go that far and that we needed to get more grants coming in,” said Pauly. “LDI had always been a convening organization, but the idea was to convert it from convening organization that supported an MBA program and did consulting to a convening organization that was a standard research center that got grants, had PhD students and research assistants, and published.”

His quest for grants soon landed a major collaborative project that brought together LDI, the University of Minnesota’s Division of Health Policy & Management, and Mathematica, a data analytics and policy research company, to form a national HCFA Center for scholarly health economics research projects related to Medicare and Medicaid operations. HCFA was the Health Care Financing Administration that later became the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

“It was frantic but really interesting work,” remembers LDI Deputy Director Joanne Levy. “There were a lot of targeted requests for which we had to come up with proposals really quickly and then run the projects. We built out a large staff and I think at times it was exhausting for Mark, who was doing so many things at once.”

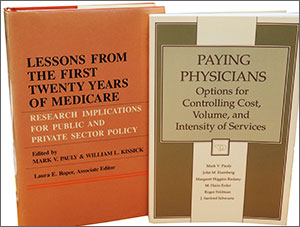

When Pauly took over LDI, the Medicare system that then covered more than 30 million people was approaching its 20th year of operation. In keeping with his intention to focus on research and publication, he thought it a perfect time to plan an LDI conference marking that 1986 anniversary. Working with Wharton Professor and LDI Governing Board member William Kissick, MD, Pauly’s office organized the October 1986 conference that brought together 60 of the country’s top health policy researchers for three days of presentations and discussions about Medicare policy at Penn. The event keynote speaker was former Administration Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare Wilbur Cohen, a key architect of the LBJ era’s greatly expanded welfare programs and the principal drafter, with William Kissick, of the Medicare legislation.

Funded by a grant from the National Center for Health Services Research, the interdisciplinary conference project also resulted in the production of a 389-page hardcover book entitled, “Lessons From The First Twenty Years of Medicare: Research Implications For Public And Private Sector Policy.” Pauly and Kissick were editors and the work of 35 other economists, physicians, sociologists, gerontologists, attorneys and political science professors made up the 16 chapters.

In their introduction, Pauly and Kissick wrote “the research results contained in this volume will clearly contribute to the quality of future policy decisions.”

LDI later launched another HCFA-funded project convening researchers in a conference focused on the contentious subject of how best to restructure the Medicare physician payment system. It was a topic on which Pauly — who would soon be named a commissioner on the federal Physician Payment Review Commission — was a national authority.

Using the same convene-and-publish dissemination model, the conference brought together more than two dozen top Medicare economics experts and distilled their papers down to a 233-page book entitled “Paying Physicians: Options for Controlling Cost, Volume and Intensity of Services.” The book provided a comprehensive overview of the subject from “Background and Theory” to “Analysis and Controls” to an analysis of Medicare’s then-current system of paying “customary, prevailing and reasonable” rates established by physicians themselves.

Capturing the overall essence of the book, Pauly — the top-listed author of the six-author work — wrote in his usual understated manner that “No one is happy with the current method of determining what Medicare will pay toward the cost of physician services.”

Community Service

Along with projects like these and the convening of regular seminars that brought in top researchers from other institutions, Pauly also got LDI actively involved in local health policy issues. He provided an office and support for LDI Senior Fellow and former Philadelphia Health Commissioner Bettina Hoerlin, PhD, who was conducting two Pew Charitable Trust-funded projects assessing health care needs in low-income communities throughout Philadelphia and its surrounding seven counties.

In a more politically sensitive project in 1987, Pauly provided LDI office space and support for the creation and operation of the Philadelphia Commission on AIDS. The move came six years after the first U.S. reports of the emerging disease in 1981. By 1986, Philadelphia had become one of the top ten cities with the most reported cases of AIDS. The Pew Charitable Trust was then putting up money to create the year-long Commission to analyze and recommend strategies and resources needed by local agencies and medical centers to more effectively respond to the spreading epidemic.

The search for a Commission Director led Pew to the LDI/Wharton Health Care Management MBA program where MBA student and RWJF Clinical Scholar Mark Smith, MD, was in his first year of studies. Smith, who spent his 1983-to-1986 residency in San Francisco General Hospital at the epicenter of the emerging HIV/AIDS outbreak, was then one of a tiny number of U.S. clinicians with extensive AIDS experience.

After agreeing to suspend his Penn studies for a year, Smith became Director of the Philadelphia Commission on AIDS, began to hire staff, and met with Mark Pauly to inquire about setting up headquarters in the LDI building.

“Mark Pauly just said ‘Sure,’ move in,” said Smith, now a Clinical Professor of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco and a physician at San Francisco General Hospital where he still treats AIDS patients. “Back then HIV/AIDS was still a very touchy subject that inspired controversy. But Mark Pauly was unfailingly supportive of both the Commission’s effort and me.” He remembered Pauly’s LDI as “a place of intellectual synergy and practical efficiency.”

“When I had a question, Mark was always glad to help answer it,” said Smith. “When I needed some kind of bureaucratic interference run for something, Mark was glad to help. We could not have done the work without the support he and LDI provided.”

Sending Students Forward

One of Pauly’s major achievements during his tenure as LDI Executive Director and Chair of the Wharton Health Care Management Department — the creation of the health care management PhD program in 1986 — almost didn’t happen. While he agreed with the outgoing Pierskalla’s view that such a program was a logical expansion of the Department’s mandate, Pauly had doubts about the level of potential student interest in a business school’s PhD program in health economics and health services research.

“Originally, I thought ‘who’s going to want to do a PhD in a narrow area like this,” said Pauly. “But over the years, I’ve repeatedly confessed how wrong I was. Surprising numbers of good people were interested and did show up in those early days — and have continued to show up decade after decade ever since.”

He also pointed out that although Harvard and a number of other universities have copied the general idea of the health care management PhD curriculum, none have exactly matched the full health economics/health services research aspects of Penn’s unique program.

“I’m so glad we did it when I think how all the PhDs we’ve produced turned out so well,” said Pauly who has mentored 30 years of PhD candidates.

Those Pauly-minted PhDs can be found in high places across the spectrum of the health services research world as well as throughout Penn’s own schools.

For instance, three former Pauly PhD students who are household names around the Philadelphia campus are Kevin Volpp, MD, PhD, Professor of Medicine and Health Care Management and founding director of the LDI Center for Health Incentives and Behavioral Economics (CHIBE); Jeffrey Silber, MD, PhD, Professor Pediatrics and Health Care Management, an international expert on outcomes measurement and severity adjustment; and Rachel Werner, MD, PhD, Professor of Medicine and Director of Health Policy and Outcomes Research, a national expert in quality measures and health care incentives.

“You learn a lot from your PhD students,” said Pauly, “and you bask in their reflected glory with such a sense of pride. In many ways the students you send forward in health services research careers are the evidence that centers like LDI or Wharton’s Health Care Management Department are worth what they cost and significantly contribute to improving the country’s health care system.”

– – –

Hoag Levins is Editor of Digital Publications at the University of Pennsylvania’s Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics (LDI) and a former reporter and editor at newspapers and magazines in Philadelphia, New York and Washington, D.C.